Suppose we have a field  in a curved spacetime, and we want to know how fast it is changing as you move in some direction in space or time. Because there is more than one possible direction to move in, we have to select a vector

in a curved spacetime, and we want to know how fast it is changing as you move in some direction in space or time. Because there is more than one possible direction to move in, we have to select a vector  which tells us which direction in the coordinate space

which tells us which direction in the coordinate space  to move in (remember,

to move in (remember,  stands for a list of all 4 spacetime coordinates.) Then we can calculate it by taking a partial derivative. If your calculus is rusty, the partial derivative

stands for a list of all 4 spacetime coordinates.) Then we can calculate it by taking a partial derivative. If your calculus is rusty, the partial derivative  is defined by:

is defined by:

at two different points (

at two different points ( and

and  ). As

). As  gets smaller, these two points get closer and closer together, so the values of

gets smaller, these two points get closer and closer together, so the values of  typically get more and more similar, but because we divide by

typically get more and more similar, but because we divide by  we end up with a nonzero answer in the limit. I've written

we end up with a nonzero answer in the limit. I've written  instead of

instead of  because I'm lazy.

because I'm lazy.

That was the formula for the partial derivative in a particular direction  (which is itself a list of 4 numbers). If we want to have a list of all 4 possible partial derivatives at each point, we can just write

(which is itself a list of 4 numbers). If we want to have a list of all 4 possible partial derivatives at each point, we can just write  without the

without the  . This is the partial derivative covector, where a covector is a thing which eats a vector (like

. This is the partial derivative covector, where a covector is a thing which eats a vector (like  ) and spits out a number. That's almost the same thing as a vector, but not quite, which is why its index is downstairs instead of upstairs. (You can convert between covectors and vectors by using the metric, e.g.

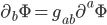

) and spits out a number. That's almost the same thing as a vector, but not quite, which is why its index is downstairs instead of upstairs. (You can convert between covectors and vectors by using the metric, e.g.  , where as usual we sum over all 4 possible values of the index.)

, where as usual we sum over all 4 possible values of the index.)

Now,  was a scalar field, meaning that it didn't have any indices attached to it. What if we tried to do the same trick with some vector field

was a scalar field, meaning that it didn't have any indices attached to it. What if we tried to do the same trick with some vector field  (or a covector

(or a covector  )? Well, nothing stops us from taking the partial derivative of a vector in the exact way:

)? Well, nothing stops us from taking the partial derivative of a vector in the exact way:

with the "t" component of a vector at another point

with the "t" component of a vector at another point  , because the definition of "t" is arbitrary. If you change the coordinate system at

, because the definition of "t" is arbitrary. If you change the coordinate system at  but not

but not  you'll get confused.

you'll get confused.

In a curved spacetime, you can only compare vectors at different points if you select a specific path to go between the two points. You can then drag (or if you prefer, parallel transport) the vector along this path, but if you choose a different path you might get a different answer.

Well here, because the points are really close, there's an obvious path to pick. Since spacetime looks flat when you zoom up really close, you can just parallel transport along the very short straight line connecting the two points. This allows you to relate the coordinate system at the starting point  to the destination point

to the destination point  . Thus, when we take the derivative, we want to compare

. Thus, when we take the derivative, we want to compare  not to the same coordinate component of

not to the same coordinate component of  , but to the parallel translated component of the vector. When we do this, we get the covariant derivative, defined as follows:

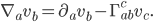

, but to the parallel translated component of the vector. When we do this, we get the covariant derivative, defined as follows:  :

:

direction and drag it a little bit in the

direction and drag it a little bit in the  direction, then

direction, then  says how much your vector ends up shifting in the

says how much your vector ends up shifting in the  direction, relative to your system of coordinates. It turns out that the bottom two indices are symmetric:

direction, relative to your system of coordinates. It turns out that the bottom two indices are symmetric:  .

.

Similarly, if you want to define the covariant derivative of a covector, you just have to attach the indices a little bit differently:

for each of the indices. How tedious! But, in the case of a scalar field

for each of the indices. How tedious! But, in the case of a scalar field  , we get off scot free: the covariant and partial derivative are just the same.

, we get off scot free: the covariant and partial derivative are just the same.

If your spacetime is flat and you use Minkowski coordinates, then  . But even in flat spacetime you can have

. But even in flat spacetime you can have  if you use a weird coordinate system, like polar coordinates.

if you use a weird coordinate system, like polar coordinates.

All of this is a little bit circular so far, since I haven't actually told you how to calculate  yet. It's just some thing with the right number of indices to do what it does. In fact, you could choose to think of the connection

yet. It's just some thing with the right number of indices to do what it does. In fact, you could choose to think of the connection  as a fundamental field in its own right, in which case there would be no need to define it in terms of anything else. But that is NOT what people normally do in general relativity. Instead they define the connection in terms of the metric

as a fundamental field in its own right, in which case there would be no need to define it in terms of anything else. But that is NOT what people normally do in general relativity. Instead they define the connection in terms of the metric  , because it turns out there is a slick way to do it.

, because it turns out there is a slick way to do it.

We want to find a way to use the metric to compare things at two different points. In other words, the metric is a sort of standard measuring stick we want to use to see how other things change. But obviously the metric cannot change relative to itself. (If you define a yard as the length of a yardstick, then other things can change in size, but the stick will always be 1 yard by definition.) Therefore, the covariant derivative of the metric itself is zero:  . But if we write out the correction terms we get:

. But if we write out the correction terms we get:

in terms of the metric. To do this, we just switch around the roles of the

in terms of the metric. To do this, we just switch around the roles of the  ,

,  , and

, and  indices to get

indices to get

directly as

directly as

. You get this by writing the metric

. You get this by writing the metric  out as a matrix and inverting it. (Technically we write

out as a matrix and inverting it. (Technically we write  where

where  is a very boring tensor which is always 1 if

is a very boring tensor which is always 1 if  and

and  are the same index, and 0 if they are different.)

are the same index, and 0 if they are different.)

So then, the connection (which allows us to transport vectors from place to place) can be written in terms of the first derivative of the metric. We'll need to take a second derivative of the metric to get the curvature  , but that will be the subject of another post.

, but that will be the subject of another post.