[Updated Dec. 28, 2017, with a revised and expanded discussion of arguments from Sean Carroll's book The Big Picture. - SC]

There are many reasons why I’m not retired, but one of the bigger ones is that I haven’t figured out yet how to get at least a quarter (if not a dollar bill) from every person who’s ever asked me how I can believe in “a god or gods” in an age of “science” and “reason”. The question is usually sincere rather than an attempt to troll, but either way, the wording alone is enough to reveal where things are headed, and the ensuing discussions have been nothing if not utterly predictable. In virtually every case the underlying narrative was based on the same handful of fashionable just-so stories, none of which appeared to have ever been questioned.

Back in days of yore, I was told, bucolic ancients looked out on a universe resplendent with mysteries they could neither understand nor predict, yet depended on for their survival. For all its dependable seasons and regularities, the universe visited floods, fires, and other tragedies on them as often as it yielded its bounty. In their attempt to understand why and find a just order to it all, they attributed these mysteries to the capricious activities of spirits called “gods” who were like us in every respect, except that they were disembodied and endowed with vast magical powers over various parts of the natural order. As the rise of science rolled back these mysteries with rational explanations, such gods were no longer needed to account for them. Eventually, the faiths based on them were rendered superfluous, and thus did Science triumph over religion (note the capital “S” and lower-case “r”).

There are so many things wrong with this it’s difficult to know where to begin. Perhaps the best way to unpack this mess is to start with the origins of the God of Classical Theism on which the Abrahamic religions are founded. These cover the professed religious beliefs of well over half of humanity and roughly 80% of North America and account for virtually every instance of the above narrative I’ve ever personally witnessed.1

Contrary to widespread belief, Classical Theism as a formal system of thought didn’t originate with Christianity or Judaism, nor was it an attempt to explain any mystery of the natural world (which makes it quite telling that the God that eventually emerged from that tradition bore a striking similarity to the uniquely monotheistic God of the Old Testament that the Israelites had been worshipping via revelation for nearly a millennium). The seminal theological question never was “is there a god?”—it is, and always has been, “why is there something rather than nothing?” In the Fifth Century BC, the Greek philosopher Parmenides formulated an axiom that was later Latinized as ex nihilo nihil fit (“out of nothing comes nothing”). Unless you believe in magic this is as straightforward as axioms get, and for nearly 2500 years no thinker of any repute has seriously challenged it. [At least not until the present day, when a handful of metaphysically illiterate Atheist physicists decided that philosophy is “dead” because it hasn’t kept up with their profession, and gave themselves permission to redefine the word “nothing” and make Magic a sub-discipline of physics. But that’s a topic for another day.] This, in turn, raised other issues. Parmenides went on to argue that change and differentiation must be illusory, for to change, he said, is for something to cease to exist in one state and begin to exist in another. Because that would require things to come from nothing, and disappear back into it, he considered it absurd. And yet, change is every bit as indisputable a fact of life as existence itself. What are we to make of these two realities, and how they relate to each other? For the next one or two centuries, philosophers of different schools argued these questions, some emphasizing the primacy of change, and others the primacy of the unchanging unity of things.

The first true leap forward came circa the mid-Fourth Century BC when Aristotle published his Metaphysics. Aristotle argued that the apparent tension between being and becoming can be accounted for if we differentiate between the actual state of existence of real-world things (or substances) and their innate potentialities for existing in different ones (later Scholastic thinkers denoted these respectively as acts and potencies). Change occurs when the active potencies of one substance causally instantiate outcomes from the passive potencies of another via four types of causality—Their material constituents (material causality), their essential form and identifying properties (formal causality), their direct physical interactions (efficient causality), and their directedness toward ends (final causality). For instance, we could say that the motion of massive objects reflects their mass and other properties (material and formal causes), and the forces they interact with (efficient causes). Aristotle would also say that they fall to the ground when dropped because the earth is their natural resting place (final causality). Similar ideas were developed by Plato, and by the Stoics and Neoplatonists after him, and eventually brought to fruition by medieval Scholastic philosophers and theologians of the Christian, Jewish, and Islamic traditions. Various schools of thought were represented in each, but most if not all, eventually converged on some combination of the following axioms;

1) The universe is contingent. Its essential nature, or form (and that of everything in it) is separate from its existence. [e.g. - We can meaningfully conceptualize horses and unicorns without regard to whether there are any.]

2) The universe is causally interconnected. The acts and potencies of its physical constituents are interrelated in rationally consistent ways.

3) The universe evolves. Per 2), its actual state of existence changes from moment to moment in dependable ways. [e.g. - Seeds grow into trees, objects fall toward a gravitational source, etc.] As such, science is a meaningful endeavor that gives us real, grounded knowledge about the way the world is.

4) Potencies may be active powers or passive capacities for change, and the events that unfold from their activity may be (formal terms again) essentially ordered, or accidentally ordered (dependent on, or independent of the continuing activity of their cause/s). [e.g. - A father has the active power to father children, and his kids will continue to exist whether he continues fathering behavior or not (accidentally ordered events). A guitar has the passive power to make music by actualizing the passive power of air to produce sound, but only if it is played by a musician, and the music will exist only while the guitar is being played (essentially ordered events).]

5) Purely passive potentialities cannot self-realize—they must be instantiated (made actual) by something else that is actual. [e.g. - wood has the passive potentiality to burn, but only if it's exposed to an actual source of heat. An infinitely long chain of stationary railroad cars (or one connected in a loop) cannot move, even though each car is connected to one that can pull it. There must be a least one engine with the active potency for inducing motion.]

6) The universe's actualities and potentialities are a mix of active powers and passive possibilities. [e.g. - A locomotive has the active power to pull a train of cars with passive potentials for motion, but also has other passive dependencies, such as the need for an engineer; you have the active power to walk or run, but not to continue living without food and water; etc.]

7) As persons with active and passive potencies of our own, we are rational, freely choosing, intentional agents. As such, our observations and thoughts can, and do, give us reliable knowledge of the universe.

From these (particularly the concept of essentially-ordered causality), they concluded that there must exist something that is pure act—the ground of all being and empowered possibility, with no passive potentialities or dependencies (Davies, 2004; Feser, 2010; 2014). Furthermore, this pure act must be;

a) Eternal - Not within, or in any way constrained by time or space.

b) Unchanging – Not evolving per any passive potencies susceptible to influences external to itself.

c) Simple - A substantial, or essential unity without parts or differing properties of the sort possessed by physical things.

d) Omnipotent - Unlimited in active powers.

e) Omniscient - Present in, and aware of, all that is.

f) Possessing both intellect and will, and as such, is the ground of all personhood (as opposed to being "a" person).

g) The intentional cause of everything else that is, and thus, the objective source of the meaning, value, and purpose of things.

Aristotle referred to this pure act as the Unmoved Mover. Christian, Jewish, and Islamic philosophers recognized Him as the God of Classical Theism who appears in the Bible and Quran. How these conclusions were reached, and how this timeless, changeless God is related to the Christian Trinity and His portrayal in the pages of both Scriptures, would fill numerous posts and is beyond our scope today. But before we proceed, a few comments are in order.

First, it’s widely believed that Aristotle’s metaphysics is dependent on his outdated physics, and therefore no longer relevant today. In his 2014 debate with William Lane Craig, Atheist physicist Sean Carroll spoke for many when he addressed transcendent causality and the universe (Carroll & Craig, 2014) stating that,

“[T]here’s a bigger problem with it, which is that it is not even false. The real problem is that these are not the right vocabulary words to be using when we discuss fundamental physics and cosmology. This kind of Aristotelian analysis of causation was cutting edge stuff 2,500 years ago. Today we know better. Our metaphysics must follow our physics. That’s what the word metaphysics means...

[T]he way physics is known to work these days is in terms of patterns, unbreakable rules, laws of nature... There is no need for any extra metaphysical baggage, like transcendent causes, on top of that. It’s precisely the wrong way to think about how the fundamental reality works.”

All of this is either false or grossly misleading. In modern analytic philosophy, Aristotelian/Scholastic concepts of ontology and causality are every bit as active a field of study as they’ve ever been (e.g. - Martin, 1997; Davies, 2004; Feser, 2014; 2015; Oderberg, 2008, etc. and sources cited therein). There are, of course, differing schools of thought on them, and their relationship to the sciences is actively debated. Some lean toward a deep interrelationship between physics and these metaphysical ideas. Others such as Edward Feser (2010; 2014; 2015) argue that the two are entirely separate realms. Aron and I fall somewhere in the middle. [For more, see Aron’s entire series of posts on Fundamental Reality.]

While it is true that modern physics treats causality differently than Aristotle and the Scholastics did (e.g. - the notions of material and formal causes are largely redundant in physics and not really needed), clearly the two realms of thought speak to the same underlying realities and even share some common language. The very “patterns, unbreakable rules, laws of nature” Carroll speaks of inherently imply an underlying unity which not only makes physics possible but fits the terms act and potency beautifully. Potentials, for instance, are a regularly recurring theme in physics, and the fact that equations of motion can be derived from them also bears a striking similarity to the Aristotelian notion of final causality. The dynamics of a falling mass can be differentially specified in terms of a static gravitational potential, but a Scholastic would say that the mass falls to earth because that’s its natural resting place. The ideas being expressed here aren’t as different as many suppose. Another common misconception is that final causality involves teleology. In fact, it’s about directedness as much as purpose or design, if not more, and applies to inanimate objects as well as living things. It’s not a huge leap to see directedness in the way static potentials lead to equations of motion.

These Aristotelian concepts are less rigorously developed of course, but conceptually at least, they substantially overlap their counterparts in physics, which implies at least some unity between the two. But at the same time, as we saw in my last post, the fact that there are numerous ontic interpretations of QM alone should give us pause before assuming that one of these realms is entirely supervenient on the other. In any event, wherever one falls on this spectrum, the one thing that isn’t true is that "our metaphysics must follow our physics". Nor is that “what the word metaphysics means" as Carroll claims. Aristotle’s Metaphysics was so named because he wrote that book after he wrote his Physics, not because the former is in any less foundational than the latter, or entirely supervenient on it (in Greek, the root meta is equivalent to the Latin post, meaning “after”).

Second, it’s worth noting that this argument, which is known as the cosmological argument, is widely misunderstood. In popular writings, particularly those of its critics, it’s almost always presented as an argument for a historical creation event based on accidentally-ordered temporal chains of causality when in fact, it’s based entirely on essentially-ordered, or simultaneous causality.2 The traditional example given by St. Thomas Aquinas and other Scholastics is that of someone pushing a ball with a stick. The passive potency of the ball for rolling motion is realized only while it is being pushed by the stick’s passive potency for doing so, which in turn is realized only while the one wielding it is exercising his/her active potency for wielding it to push objects. The entire causal chain is simultaneous in the present moment and has nothing whatsoever to do with any cause or causes that may have existed even a few seconds prior. In fact, Aquinas, who developed the argument better than anyone else in history, famously believed that it wasn’t possible to demonstrate that the universe had a temporally-ordered causal beginning. He believed it did because Scripture said so, but he felt that observation and philosophical arguments alone couldn’t demonstrate that. Today, of course, Carroll’s dismissal of transcendent causes notwithstanding, the evidence for a beginning is considerable and whether they admit it or not, a source of dismay for Atheists. Aquinas’ claims to the contrary are relevant here, only to the extent that they emphasize that time-ordered causality plays no role in traditional cosmological arguments.

Furthermore, in the writings of Aristotle and the Scholastics, the term move denotes change in general, not just rectilinear motion as we understand it. To them, changes in any property—including say, color, temperature, or even a beginning of existence—would be considered “movement”. Interestingly, Carroll misses the subtleties of this as well. In his book The Big Picture (2017) he tells us that,

"[T]he whole structure of Aristotle's argument for an unmoved mover rests on his idea that motions require causes. Once we know about conservation of momentum, this idea loses its steam... What matters is that the new physics of Galileo and his friends implied an entirely new ontology, a deep shift in how we thought about the nature of reality. 'Causes' didn't have the central role that they once did. The universe doesn't need a push; it can just keep going." (My emphasis)

Clearly, this argument doesn’t account for accelerated motion, which anyone who’s ever dropped a $600 cell phone off a balcony will tell you, is quite real. For some reason, this doesn’t seem to concern him. The real puzzle, however, is that he acknowledges that Aristotelian motion is a much broader concept than mere spatial displacement, and even uses the word transformation to describe it. Why he imagines that an argument against an untransformed transformer could be based on rectilinear motion alone is anyone’s guess. The metaphysical importance of conservation of momentum, he tells us, is “hard to overemphasize” and he sees in it an underlying principle that in his view, can be extrapolated to all contingency and change. But how this is supposed to work in practice is never clarified. Throughout this chapter (aptly titled The World Moves by Itself) he speaks of “causes” and “motions“ in the most general metaphysical sense and uses those terms interchangeably. But the only working examples he offers involve frictionless displacement of objects like coffee cups, which he supplements with glib remarks about how terms like “cause” and “effect” aren’t found in physics textbooks (as though the language of physics and its methods are the only ones that are meaningful in the real world).

Near as I can tell, Carroll believes that conservation of momentum is built on a metaphysical foundation that generalizes to all conservation laws. Essentially, this amounts to the claim that Noether’s theorem (and possibly its extension to quantum field symmetries) constitutes a sort of “blood-brain barrier” isolating all contingent change in the universe from the interventions of any creator god. If so, the problems with this are obvious. For starters, he points out (correctly) that Aristotle’s unmoved mover was later fully developed by Aquinas. As we’ve already seen, essentially-ordered causality and God as the universe’s sustainer as well as its creator are foundational concepts in his thought. Anyone even remotely familiar with this will immediately recognize a universe that “keeps going” after an initial “push” as one based on an independent temporally-ordered causal chain that some divine machinist occasionally tinkers with—an argument that Aquinas went to great lengths to refute, and clearly not the cosmological argument he defended. Second, attributing virtually all contingency and change to conservation laws is, to say the least, a stretch. What sort of conservation law gave me blue rather than brown eyes, for instance, or required me to order a triple-shot cappuccino this morning rather than a hot chocolate? Even if we ignore all this, there’s one rather large elephant in the room that isn’t being addressed. The sort of conservation laws Carroll is appealing to are only valid over locally flat regions of space-time. For the universe as a whole, neither momentum nor energy is even well-defined, much less conserved (MTW, 2017)—a fact that he’s not only aware of but has written about elsewhere himself (Carroll, 2010), yet now conveniently chooses to forget.3

It’s odd that Carroll manages to muddle so many metaphysical concepts as completely, and chronically, as he does. Unlike many scientists these days, he has a background in philosophy (having minored in it as an undergraduate) and is known for his thoughtfulness and attention to detail with metaphysical topics. He’s repeatedly, and rightly, called out many of his colleagues for their Philistine recklessness in these areas and with philosophy in general. If anyone should know better, it would be him.

Finally, it should also be noted that the history of thought on God’s nature isn’t quite as monolithic as I perhaps made it sound. In recent years, for instance, some theologians and philosophers of religion have questioned the notions of God as grounded personhood (as opposed to personality), His simplicity, and the claim that He’s timeless and unchanging. God, it’s argued, cannot be meaningfully omniscient and loving, as He’s presented in the Bible and Quran, unless He has attributes that manifest in a personality, not unlike ours, and He in some sense experiences time (although opinions as to whether His time maps onto the space-time of our experience, and if so, how). This school of thought, referred to by some as theistic personalism, has been particularly popular among advocates of presentism (the so-called “A-Theory” of time). It’s more notable advocates include Richard Swineburne, Alvin Plantinga, J.P. Moreland, and William Lane Craig.

Theistic personalism is a relatively late development in the history of Classical Theism and hasn’t gained widespread acceptance among theologians and philosophers of religion (Davies, 2004). The traditional arguments for the simplicity and timelessness of the God of Classical Theism as presented above are formidable and well-supported not only by metaphysics but the Abrahamic Scriptures as well. The apparent difficulties presented by a timeless God in changing history are not as difficult as they may seem at first blush either. Once we realize that if God is omnipresent throughout His created space-time, and interacting with it at every point according to His Will, He will appear to change from the standpoint of time-bound creatures like us, much the way a static landscape appears to change to the passengers of a car driving through it. Dispensing with all this simply to bring God more in line with our experience adds layers of arbitrary, and unnecessary metaphysical complexity that cry out for Occam’s Razor. As if that weren’t enough, it runs badly afoul of physics as well. The presentism that it most naturally fits has numerous issues, not the least of which are the difficulties of reconciling it with the Lorentz boost. While it is possible to make presentism work in a relativistic framework (Copan & Craig, 2004), the match ain’t exactly made in Heaven and IMHO at least, creates far more problems than it solves. Nevertheless, theistic personalism does have its place in modern theological discourse, and it has been ably defended by its proponents (Moreland & Craig, 2003).

There… Now that all the fine print is out of the way, let’s return to our seven-axiom argument for the existence of God. At this point, several things should be readily apparent.

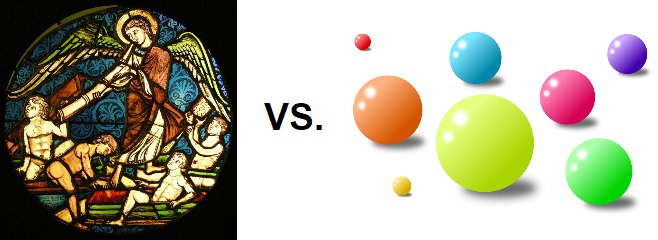

1) God is not “a god”

When Atheists (or more commonly, New Atheists) speak of "a god or gods" what they invariably have in mind are demigods—minor deities of the sort one finds in ancient mythologies. These are the disembodied space and time-bound magical spirits central to their narrative. In The God Delusion Richard Dawkins (2008) states that,

"I have found it an amusing strategy, when asked whether I am an atheist, to point out that the questioner is also an atheist when considering Zeus, Apollo, Amon Ra, Mithras, Baal, Thor, Wotan, the Golden Calf and the Flying Spaghetti Monster. I just go one god further."

The problem with this is obvious—the “gods” he names bear no resemblance whatsoever to the God of Classical Theism. In Greek mythology, Zeus had a family tree like us. He was the child of the Titans Chronos and Rhea, and they were, in turn, descended from the primordial Greek deities (Wikipedia, 2016). Like the rest of the Greek pantheon, not only was he a time-bound spirit, he was earth-bound as well and "lived" at a physical location (Mt. Olympus). In fact, as often as not, such demigods were deified human rulers. Case in point, the Akkadian ruler/gods Gilgamesh and Naram-Sin who respectively ruled during the late Third and early Second Millennia BC (Armstrong, 2015).

God on the other hand (note the capital “G”), is the ground of all being and personhood. He is neither space and time-bound nor an instantiation—there is no general class of things called "grounds of all being" of which He can be said to be one example among many. The very claim that there could be more than one such ground is inherently self-contradictory. It’s no accident that the Abrahamic religions are all monotheistic. And as the creator of all else that exists—including the very space-time manifold whose geometry is, per general relativity, related to the mass-energy and momentum it contains—calling Him a demigod amounts to claiming that He's bound by His own creation, and dependent on it for His existence. That, my friends, is patently absurd. Saying that God is "a god” isn't merely wrong, it's a category error.

Interestingly, the distinction we find today between the anthropomorphic personified God of televangelist’s sermons and children’s picture Bibles, and the God of Classical Theism was every bit as true in Aristotle’s day as well. Then, as now, philosophers distinguished between Everyman’s bearded, gray haired Zeus who threw thunderbolts from Mt. Olympus, and the classical theistic "Zeus" (or more properly, Greek primordial God) of formal thought. If this were the 4th Century BC, New Atheists like Dawkins would be out in front of the Athens Peripatetic school in togas beating their well-inflated chests about "a zeus or zeus'es," and Aristotle would be the one biting his tongue and doing whatever could be done to educate them. Some things never change… ;-)

2) God is not a hypothesis

Science doesn’t deal in “facts” (at least not as most people understand that word). More correctly, it deals with data. One begins with reproducible measurements of some observed phenomena (e.g. – the power density spectrum of the cosmic microwave background, or tracks emerging from particle collisions in a cloud chamber). One or more hypotheses are formed to account for them, and the most viable of these are developed into formal theories from which the outcomes of further, yet untested observations can be predicted. In the case of physics, this generally means a set of differential equations and boundary conditions, a Lie algebra that embodies an expected symmetry, or the like. Failure of a theory’s predictions is its null hypothesis and counts as evidence against it. If further experiments yield the predicted outcomes, confidence in the theory grows, and if not, suspicion does. In this sense, hypotheses that make no testable predictions cannot meaningfully be called scientific.4

Enter our axioms 1) through 7). Though all are based on observation, and scientific illustrations could be given for them, they cannot be called “data” in any scientifically meaningful sense. How does one create a “dataset” to quantify concepts like act and potency, and use it to validate a ground of all being and personhood and the contingency of the universe? What they are, is a set of metaphysical axioms about the underlying ontic nature of the universe, and God (again, note the capital “G”) isn’t a hypothesis we postulate to account for them—He’s a formally reasoned conclusion derived from them.

Alright, before anyone blows a gasket, let me be clear about what I mean. No, I am not saying that the existence of God can be logically/mathematically proven. If it were that easy Atheism wouldn’t be a worldview worth discussing, and its proponents wouldn’t include some of the finest minds in history. What I am saying is that it’s a different sort of argument than the traditional data -> hypothesis -> test methodology science relies on. Claiming that there’s no evidence for God, as opposed to "a god or gods," is like claiming that there’s no “evidence” for “an equation or equations” called the Mean Value Theorem of Calculus. The Mean Value Theorem isn’t a hypothesis—it’s a formal proof that begins with certain axioms (e.g. – a continuous manifold, monotonic everywhere differentiable functions, etc.). The extent to which one accepts those axioms is the extent to which one accepts the conclusion. Likewise, to reject that conclusion is to reject the axioms it begins with.

Which brings us to the next point…

3) Atheism is not a null hypothesis

Finally, we arrive at New Atheism's most beloved get-out-of-jail-free card—the belief that it's merely the rejection of Theism, and as such, a null hypothesis that needs no defense. Sam Harris (2008) minces no words when he states that,

“’Atheism’ is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a ‘non-astrologer’ or a ‘non-alchemist.” … Atheism is nothing more than the noises people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.”

A New Atheist friend and colleague once put it to me even more starkly on social media,

“An Atheist is one who rejects the claims made by theists. An Atheist is simply a person who is not a theist. Atheism is not in itself a claim, and as such, simply cannot be false. Only claims can be proven false; a lack of claim cannot be said to be false. How can I be wrong when I say 'you haven't presented a compelling argument for your case'?” (My emphasis)

Clever, aren’t we? Don't state your claims directly, frame them as a rejection of someone else's… then conveniently excuse yourself from any responsibility for a proper defense of them, and set the standard of proof however high it needs to be to protect you, infinitely if necessary. Sleight of hand like this isn’t just bread-and-butter for New Atheists of course. Creationists and climate change skeptics rely heavily on it as well. Denial... it ain't just a river in Egypt anymore! ;-)

To be fair, this would be valid if we were postulating the activity of demigods in the created order as one possible explanation for some phenomenon. If my fishing buddy insists that the nibble I just had was a trout, I’m under no obligation to defend my skepticism when we both know the pond is full of bass and catfish as well. The burden of proof is on him to produce evidence for his “trout” theory as opposed to a bass or catfish one. But as we’ve seen, that’s not what’s happening here. We aren’t offering any “god hypothesis” to account for something in the natural world, whether it be trout in a pond or anything else. We’re formally demonstrating that a set of metaphysical axioms requires His existence. Atheists like Harris and my friend aren’t rejecting belief in “a god or gods”—they’re rejecting the metaphysical axioms that lead to the God of Classical Theism. That cannot be done in a vacuum without committing oneself to some, or all, of the following counter-axioms;

8) The universe is a brute fact. Science may reveal its countless subtleties and underlying unities, but ultimately it just has the contingent features it does rather than an infinite number of other possibilities. There is no reason why... it just is that way.

9) Per 8), the beginning of the universe's existence (13.73 billion years ago) is also a brute fact. There is no reason why... it just created itself from nothing.

10) There is no such thing as causality—only events unfolding in certain ordered ways. “Causality” is just a concept we use to describe the appearance of mechanism between bits of stuff (what I referred to above as "interactions"), but ultimately those events are, to use David Hume's term, "loose and separate." They have no inherent relationship to each other.

11) Matter does not actually possess any inherent properties or essential natures of the sort that could be described in terms of essence or potency (as I defined them above). Reality is ultimately just "bits of stuff" mechanically interacting according to mathematical laws expressed in terms of parameters that give the appearance of such. [“Um, ‘interactions’ and ‘laws’…? Didn’t you just say in 10) that…?” “Silence Dorothy! Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain...!”]

12) The rationality of the laws of nature—that those "loose and separate" events between bits of stuff happen to unfold according to what physicist Eugene Wigner called "the unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics—is also a brute fact. There is no reason why... it just is that way.

13) "Loose and separately" ordered bits of stuff are blind, and as such the universe ascribes no objective value or purpose. Everything in it, including us, is a byproduct of random, meaningless accidents—what Richard Dawkins called "blind, pitiless indifference" (Dawkins, 1996). Thus, morality is either nihilistic or entirely subjective.

14) Alternately, if objectively normative moral values do exist—yours, mine, or anyone else's—then they too are brute facts. There is no reason why... they just are what they are. [“But my goodness gracious… isn’t it marvelous how nicely they align with mine…?”]

15) Consciousness and personhood are illusory. To again use David Hume's term, we're just "bundles of percepts" in bodies made up of bits of stuff behaving according to deterministic laws. [“Um, ‘deterministic’…? Didn’t you say in 10) that…?” “Silence Dorothy! Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain...!”] "You" or "I" are concepts we use to describe our experience of the neural activity in our brains, and how it affects our perceptions and behaviors. Beyond that, we are no more “persons” in the sense of being freely empowered, intentional, and possessing rational agency than an email server is (analytic philosophers refer to this viewpoint as eliminative materialism).

16) Though we are accidentally evolved "bundles of percepts," our perceptions and reasoned thoughts are reliable sources of knowledge of the deepest inner workings of the universe and ourselves.

Notice that these aren’t mere “rejections” of anything. Like 1) through 7), they’re positive metaphysical assertions about the ontic foundations of the universe, and as such, they have rational consequences. We can reject belief in mythological demigods, invisible dragons, or the Flying Spaghetti Monster if we like. But we cannot reject the God of Classical Theism without committing ourselves to a fully developed and properly defended philosophy of Materialism, any more than we can reject belief in light without accepting belief in darkness—which is of course, precisely what every Atheist philosopher of any repute in history has labored to produce. David Hume, Friedrich Nietzsche, Bertrand Russell, Antony Flew… these and many other luminaries devoted their lives to producing materialistic philosophies of nature, mind, and ethics based on some, or all of the above counter-axioms, and published countless influential works in the process (Hume, 2000; 2017; Nietzsche, 2000; Russell, 1967; 2017; Flew, 2005 to name a few).

According to Harris and my friend, all of that was a waste of time—what these and countless other luminaries should’ve been doing, was belittling televangelists and suicide bombers on social media and in TED talks to like-minded audiences. They, of course, knew better. Those who insist that there’s no evidence for “a god or gods” are merely demonstrating that they don’t even understand the question, much less have a properly thought out answer for it.5

A reporter once presented the late Samuel Shenton, then president of the Flat Earth Society, with a photograph of earth taken by the Apollo 13 astronauts from roughly 150,000 miles distance. Shenton stared long and hard at it, after which he began to nod. “Yes,” he finally said… “It is easy to see how the untrained eye could be fooled by that picture!” Well-trained eyes are becoming an increasingly important part of the modern intellectual landscape… particularly in secular communities that wear their claims to “reason” and objectivity like golden tiaras. But as I said in my last post, if our only tool is a hammer then sooner or later everything will look like a nail. Though some would deny it (sincerely, I believe), to many in these communities, science is no longer a discipline. It has become a religion in its own right—Scientism, the sacred Oracle whose mighty outstretched hand no question of earth, sky, heart, or soul can elude. Its practitioners are no longer experts, but authorities—high priests of the goddess Reason, whose metaphysical pronouncements are every bit as authoritative as the theistic fundamentalist dogmas they, often rightly, deride.

Nowhere is this more true than with physics—a discipline that not only knocks on the door of many metaphysical questions, but immerses itself in counterintuitive mysteries that at times seem almost magical, and higher mathematics that to the guy on the street are every bit as arcane as ancient hieroglyphics… so much so that a term has even been coined for it: physics envy. And human nature being what it is, once a scientist has been elevated from mere expertise to the august status of High Priest, he/she becomes an authority not only in their own field, but in beer brewing, Elizabethan poetry, personal lubricants, or any other topic for which it’s their whim to have an opinion. Anymore, hardly a week goes by that I don’t see yet another news story extolling Stephen Hawking’s latest complaints and/or warnings about society, international politics, or the impacts of technology on the future of humanity—as though expertise in quantum cosmology qualifies him to speak to any of those topics. [That isn’t Hawking’s fault of course. Scientists rarely ask for the deification so glibly bestowed on them by a credulous public.]

Unfortunately, there’s one big problem with all this… Like it or not, science is a discipline, not an Oracle. A powerful discipline to be sure, and one that has rolled back the mysteries of the universe like no other, but a discipline nonetheless, and for damn sure, no more either. And like all other disciplines, it is, and always will be, but one tool among many. As such, it lends itself to many but not all questions, and the experts who wield it are fallen mortals every bit as subject to their own hopes, fears, and human limitations as we are. It’s the height of naivete and outright hubris to pretend that we can cleanse it of our own limitations and treat it like a magic wand that can answer every question, meet every moral, spiritual, and existential need, and endow our existence with purpose… and we pay a steep price when we do. The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead once said,

“Scientists, animated by the purpose of proving they are purposeless, constitute an interesting subject for study.”

True that.

Footnotes

1) I’m not knowledgeable enough about Hinduism to speak with any authority about it, but its concept of Brahman as the Absolute appears to bear some similarity to the God of the Abrahamic traditions. If so, then including it in this list would raise the tally of humanity that embraces some version of the God of Classical Theism to nearly 70%.

2) There is one version of the cosmological argument that does presume that the universe had a beginning—the Kalam cosmological argument whose most notable proponent is William Lane Craig. However, it isn’t based on time-ordered causality either. The Kalam argument differs from the traditional one in that it contains two additional premises: Whatever begins to exist has a cause; and that this cause must be transcendent because (per Parmenides) the universe cannot efficiently cause itself. But like the traditional cosmological argument, it takes this cause to be essentially-ordered as well.

3) Conservation of energy is suspect even for a flat universe. In this case, the global energy of the universe can be derived from the Poisson equation, which has no solution for an unbounded fluid. There is one, and only one case in which the universe can be said to have a well-defined global energy, and that is if it’s closed, in which case, a global definition of energy/momentum flux (gravitationally equivalent to Gauss’ Law) would require it to be zero.

4) Interestingly, some physicists and philosophers are now beginning to question this, and their reasons are rather surprising. In recent years, multiverse models based on eternal inflation and the so-called string landscape have in the eyes of many physicists, become “the best game in town” for a “theory of everything” that could potentially resolve many issues in physics and cosmology. The inflationary framework accounts beautifully for a few cosmological conundrums that would otherwise be inexplicable (e.g. – the “flatness" problem, and the uniformity of the cosmic microwave background). But in the absence of a viable candidate for the inflaton (as of this writing), the scalar potential/s in inflationary models are flexible enough that for the time being at least, validating the framework has largely proven to be a whack-a-mole exercise. For every model that’s been observationally ruled out, more have sprung up. Likewise, while string theory has led to much progress in many areas, it has also proven excessively flexible—so much so that since its inception more than 40 years ago, it has yet to make a single testable prediction. Furthermore, the scale on which it’s real nuts and bolts are expected to reveal themselves requires testing at energies that will never be accessible to us (Woit, 2007). For all intents and purposes, this renders string landscape multiverse models virtually untestable… even in principle. However, in spite of these problems, they offer two really big carrots that in addition to their other strengths have proven irresistible to many physicists: a) In conjunction with anthropic arguments, they currently offer the only workable explanations of fine tuning that are based solely on physics; and b) Though vulnerable to some formidable arguments that the universe had a beginning, eternal inflation does offer at least some hope for avoiding a creation event. Technically, “eternal” inflation is a reference to future-eternal inflation and thus a bit of a misnomer. A past-eternal universe would run afoul of the BGV theorem; there are a few ways to get around it, although the best of them are contrived to say the least.

The bottom line is that as of this writing, the string landscape/eternal inflation multiverse offers the only path forward for cosmology that doesn’t smack of a Creator. Given the theistic alternatives, it’s little wonder that many Atheist physicists (most notably Sean Carroll) are willing to accept these limitations and argue that it’s time to dispense with testable predictions in science. If a theory is “elegant” (in their view) and at least fits observation, it is de-facto true. Likewise, it also comes as no surprise that many of the strongest opponents of this movement (known as Post-Empiricism) are Christians like George Ellis (Ellis & Silk, 2014).

Ironically, the shoe is now on the other foot. Atheists who for so long have (often rightly) accused religious believers of clinging to comfortable dogmas without evidence, are now the ones insisting that science should be divorced from it. When their backs are against the wall (and to their credit IMHO), they prove to be every bit as mortal as people of faith. And like us, they cherish their worldviews enough that they’ll occasionally struggle for their preservation even to a fault.

5) Antony Flew is a particularly telling case in point. Often referred to as the Father of 20th Century Atheism, he was arguably the most important Atheist philosopher of his age. His seminal work God and Philosophy (2005), which was originally published in 1966, almost single-handedly shaped the direction of Atheist thought and scholarship during his lifetime. Shortly before his death in 2010, he shocked the secular world when he set aside his life’s work and said that based on reason and evidence, he could no longer deny the existence of God (Flew & Varghese, 2008). Flew didn’t conclude with a God who is personal, as in the Bible and Quran, nor did he embrace any major religion. But his God did bear a striking similarity to the God of Classical Theism, and he gave a particularly deferential hat-tip to… Christianity.

Needless to say, this dealt New Atheists a narcissistic injury which they still haven’t recovered from to this day. The reaction was immediate, and what one would expect. Despite his life’s work, Flew was promptly branded an apostate to the True Faith and excommunicated. Dawkins (2008) fumed about his “tergiversation” (as though using the biggest and most impressive word he could find in a crossword puzzle would somehow convert bullshit into a valid argument). Others resorted to smear campaigns (up to and including accusing him of senility), and intellectual cross-burnings that would make even the flock of Westboro Baptist Church blush. The one thing that was not, and to this day has not been produced, is a properly researched and soundly defended critique of his stance.

Perhaps New Atheists are as offended by religion as they are because they have more in common with blindly dogmatic religious fundamentalists than they’re prepared to admit. Few people evoke as much hate as those who hold a mirror up to us that we don’t want to face.

References

Armstrong, K. (2015). Fields of blood: Religion and the history of violence. Anchor; Reprint edition (September 15, 2015). ISBN-10: 0307946967; ISBN-13: 978-0307946966. Available online at www.amazon.com/Fields-Blood-Religion-History-Violence/dp/0307946967/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1499969508&sr=8-1. Accessed July 13, 2017.

Carroll, S. 2010. Energy Is Not Conserved. Discover, Feb, 22, 2010. Online at http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/cosmicvariance/2010/02/22/energy-is-not-conserved/#.WkLCkkqnFaQ. Accessed Dec. 26, 2017.

Carroll, S. (2017). The Big Picture: On the Origins of Life, Meaning, and the Universe Itself. Dutton; Reprint edition (May 16, 2017). Chap. 3. ISBN-10: 1101984252; ISBN-13: 978-1101984253. Available online at www.amazon.com/Big-Picture-Origins-Meaning-Universe/dp/1101984252/ref=mt_paperback?_encoding=UTF8&me=. Accessed Dec. 27, 2017.

Carroll S. & W. L. Craig. (2014). “God and Cosmology: The Existence of God in Light of Contemporary Cosmology”. New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, New Orleans, LA – March 2014. Transcript available at www.reasonablefaith.org/god-and-cosmology-the-existence-of-god-in-light-of-contemporary-cosmology. Accessed July 14, 2017.

Copan, P., & Craig, W. L. (2004). Creation out of nothing: A biblical, philosophical, and scientific exploration. Baker Academic (June 1, 2004). ISBN-10: 0801027330; ISBN-13: 978-0801027338. Available online at www.amazon.com/Creation-out-Nothing-Philosophical-Exploration/dp/0801027330/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1500324234&sr=8-1&keywords=Creation+out+of+nothing. Accessed July 17, 2017.

Dawkins, R. (1996). River out of Eden: A Darwinian view of life. Basic Books; Reprint edition. ISBN-10: 0465069908; ISBN-13: 978-0465069903. Available online at www.amazon.com/River-Out-Eden-Darwinian-Science/dp/0465069908/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1499814281&sr=1-1&keywords=river+out+of+eden. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Davies, B. (2004). An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Oxford University Press; 3 edition (January 8, 2004). ISBN-10: 0199263477; ISBN-13: 978-0199263479. Available online at www.amazon.com/Introduction-Philosophy-Religion-Brian-Davies/dp/0199263477/ref=sr_1_3?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1499974934&sr=1-3&keywords=brian+davies. Accessed July 13, 2017.

Dawkins, R. (2008). The God Delusion. Mariner Books; Reprint edition, ISBN-10: 0618918248; ISBN-13: 978-0618918249. Available online at www.amazon.com/God-Delusion-Richard-Dawkins/dp/0618918248/ref=sr_1_1_title_1_pap?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1408044395&sr=1-1&keywords=god+delusion. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Ellis, G., & Silk, J. (2014). Scientific method: Defend the integrity of physics. Nature, 516(7531). Available online at www.nature.com/news/scientific-method-defend-the-integrity-of-physics-1.16535. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Feser, E. (2010). The last superstition: A refutation of the new atheism. St. Augustines Press; 1St Edition edition (December 10, 2010). ISBN-10: 1587314525; ISBN-13: 978-1587314520. Available online at www.amazon.com/Last-Superstition-Refutation-New-Atheism/dp/1587314525/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1499974707&sr=8-1. Accessed July 13, 2017.

Feser, E. (2014). Scholastic Metaphysics. Editions Scholasticae. ISBN-10: 3868385444; ISBN-13: 978-3868385441. Available online at www.amazon.com/Scholastic-Metaphysics-Contemporary-Introduction-Scholasticae/dp/3868385444/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1464406953&sr=8-3&keywords=feser. Accessed July 13, 2017.

Feser, E. (2015). Neo-scholastic Essays. St. Augustines Press; 1 edition (June 30, 2015). ISBN-10: 1587315580; ISBN-13: 978-1587315589 Available online at www.amazon.com/Neo-Scholastic-Essays-Edward-Feser/dp/1587315580/ref=pd_sim_14_3?ie=UTF8&dpID=51vOUR5k8eL&dpSrc=sims&preST=_AC_UL320_SR214%2C320_&psc=1&refRID=MP3S70WMRDF7N9VQNPMA. Accessed July 15, 2017.

Flew, A. (2005). God and philosophy. Prometheus Books (April 8, 2005). ISBN-10: 1591023300; ISBN-13: 978-1591023302. Available online at www.amazon.com/God-Philosophy-Antony-Flew/dp/1591023300/ref=mt_paperback?_encoding=UTF8&me=. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Flew, A., & Varghese, R. A. (2008). There is a God. HarperOne; unknown edition (November 4, 2008). ISBN-10: 0061335304; ISBN-13: 978-0061335303. Available online at www.amazon.com/There-God-Notorious-Atheist-Changed/dp/0061335304/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1500661815&sr=1-1. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Harris, S. (2008). Letter to a Christian Nation. Vintage; Reprint edition. ISBN-10: 0307278778; ISBN-13: 978-0307278777. Available online at www.amazon.com/Letter-Christian-Nation-Sam-Harris/dp/0307278778/ref=sr_1_6_title_1_pap?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1408131913&sr=1-6&keywords=sam+harris. Accessed July 11, 2017.

Hume, D. (2017). An enquiry concerning human understanding. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (July 1, 2017). ISBN-10: 1461180198; ISBN-13: 978-1461180197. Available online at www.amazon.com/Enquiry-Concerning-Human-Understanding/dp/1461180198/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1500660885&sr=8-3. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Hume, D. (2000). A treatise of human nature. Oxford University Press; New Ed edition (February 24, 2000). ISBN-10: 0198751729; ISBN-13: 978-0198751724. Available online at www.amazon.com/Treatise-Human-Nature-Oxford-Philosophical/dp/0198751729/ref=sr_1_13?ie=UTF8&qid=1500660885&sr=8-13&keywords=david+hume. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Martin, C. F. (1997). Thomas Aquinas God and Explanations. Edinburgh University Press; 1 edition (June 30, 1997). ISBN-10: 0748609016; ISBN-13: 978-0748609017. Available online at www.amazon.com/Thomas-Aquinas-Explanations-Christopher-Martin/dp/0748609016/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1500142014&sr=8-1&keywords=Thomas+Aquinas+God+and+Explanations. Accessed July 15, 2017.

Misner, C. W., Thorne, K. S., & Wheeler, J. A. (MTW). 2017. Gravitation. Princeton University Press. ISBN-10: 0691177791; ISBN-13: 978-0691177793. Chap. 20.2. Online at www.amazon.com/Gravitation-Charles-W-Misner/dp/0691177791/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1514324449&sr=8-1&keywords=gravitation. Accessed Dec. 26, 2017.

Moreland, J. P., & Craig, W. L. (2003). Philosophical foundations for a Christian worldview. IVP Academic; unknown edition (April 28, 2003). ISBN-10: 0830826947; ISBN-13: 978-0830826940. Available online at www.amazon.com/Philosophical-Foundations-Christian-Worldview-Moreland/dp/0830826947/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1460753368&sr=8-1&keywords=Philosophical+Foundations+for+a+Christian+Worldview. Accessed July 17, 2017.

Nietzsche, F. (2000). Basic Writings of Nietzsche. Modern Library; Modern Library edition (November 28, 2000). ISBN-10: 0679783393; ISBN-13: 978-0679783398. Available online at www.amazon.com/Writings-Nietzsche-Modern-Library-Classics/dp/0679783393/ref=tmm_pap_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=1500661604&sr=1-7. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Oderberg, D. S. (2008). Real essentialism. Routledge; 1 edition (January 30, 2008). ISBN-10: 041587212X; ISBN-13: 978-0415872126. Available online at www.amazon.com/Essentialism-Routledge-Studies-Contemporary-Philosophy/dp/041587212X/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1500142092&sr=8-2&keywords=Thomas+Aquinas+God+and+Explanations. Accessed July 15, 2017.

Russell, B. (1967). History of Western Philosophy. Simon & Schuster/Touchstone (October 30, 1967). ISBN-10: 0671201581; ISBN-13: 978-0671201586. Available online at www.amazon.com/History-Western-Philosophy-Bertrand-Russell/dp/0671201581/ref=mt_paperback?_encoding=UTF8&me=. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Russell, B. (2017). The problems of philosophy. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform (April 21, 2017). ISBN-10: 1545507635; ISBN-13: 978-1545507636. Available online at www.amazon.com/Problems-Philosophy-Bertrand-Russell/dp/1545507635/ref=mt_paperback?_encoding=UTF8&me=. Accessed July 21, 2017.

Wikipedia. (2016). Greek primordial deities. Available online at en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greek_primordial_deities. Accessed July 17, 2017.

Woit, P. (2007). Not even wrong: The failure of string theory and the search for unity in physical law. Basic Books; Reprint edition (September 4, 2007). ISBN-10: 0465092764; ISBN-13: 978-0465092765. Available online at www.amazon.com/Not-Even-Wrong-Failure-Physical/dp/0465092764/ref=mt_paperback?_encoding=UTF8&me=. Accessed July 16, 2017.

discipline

raised upright but the sphere is a perfect shape!

raised upright but the sphere is a perfect shape!