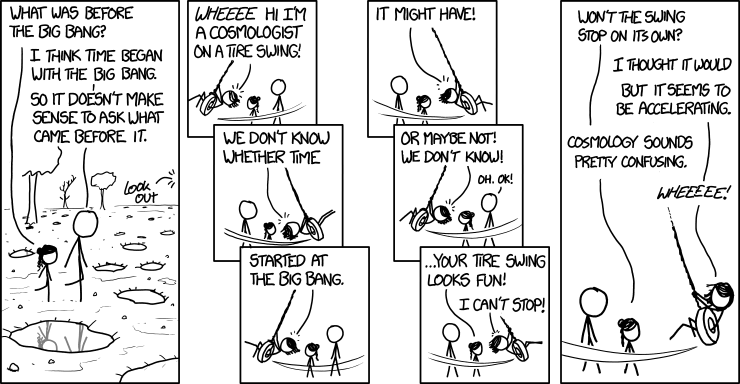

from http://www.xkcd.com/1352/.

We have now come to the end of my series about whether or not the universe had a beginning. This is part of a longer series dissecting the debate between St. William Lane Craig and Sean Carroll. I started out with some general reflections on the debate:

Thoughts on the Carroll-Craig Debate

God of the Gaps (see also: Gaps at the Dinner Table)

Then I started talking specifically about possible evidence from physics for and against the universe having a beginning. For ease of understanding I'm going to label each main new argument with FOR or AGAINST to define its main orientation, but the posts also deal with the various counterarguments (that's the tire swing going back and forth above...). I've provided an executive summary of each of these posts, so that you can easily see the main thrust of what I said. Minus all the caveats, hedging, and detailed explanations my scientific training tends to encourage.

(I've heard that politicians hate talking to scientists because, like the Elves in Tolkien, we seldom give a straight answer to a question. In scientific cultures, we show "sincerity" by discussing all the problems and caveats with our ideas, whereas in political circles this sounds like insincere waffling designed to please too many people...)

Did the Universe Begin? I: Big Bang Cosmology (FOR, as far as it goes...)

- the classical Big Bang Model predicts an initial singularity where time began

- tentative because quantum effects were important and invalidate our usual geometrical notions

- also tentative because we don't really know how inflation began

Did the Universe Begin? II: Singularity Theorems (FOR)

- classical General Relativity theorems by Hawking and Penrose

- assumptions of Hawking theorem invalid during inflationary epoch

- Penrose theorem says that if space is infinite, there was a beginning

- Penrose theorem invalid in quantum situations, but my work suggests that it might be extendable to quantum gravity, if horizons always obey the 2nd law of thermodynamics.

Did the Universe Begin? III: BGV Theorem (FOR)

- if the universe has a positive average expansion, then "nearly all" geodesics cannot be extended infinitely to the past

- implies that inflation had to have a beginning in time, at least in some places

- can evade theorem by a "bouncing" cosmology where the universe contracts and then expands

Did the Universe Begin? IV: Quantum Eternity Theorem (AGAINST)

- if the usual rules of QM hold at all times, you can calculate what the state would be at any time to the past or future.

- in realistic cosmologies the energy is probably either zero or undefined, making the theorem inapplicable.

Did the Universe Begin? V: The Ordinary Second Law (FOR)

- given reasonable assumptions, 2nd law of thermodynamics requires a beginning

- most plausible way to evade this is to postulate that the "arrow of time" reverses

- such models would have a "thermodynamic beginning" but no "geometrical beginning"

Did the Universe Begin? VI: The Generalized Second Law (FOR)

- second law of thermodynamics also seems to apply to cosmological horizons

- can be used like ordinary 2nd law to argue for beginning

- can also be used as singularity theorem (see II above)

- this closes certain loopholes, but if the universe is finite and the arrow of time reverses, a bounce may still be possible.

Did the Universe Begin? VII: More about Zero Energy

- a more technical explanation of why the energy of the universe can be zero

Did the Universe Begin? VIII: The No Boundary Proposal (AGAINST/FOR)

- a beautiful set of speculative ideas which unify the "laws of physics" with the "initial conditions", by providing a rule for what the state of the universe is.

- contrary to popular conceptions, the Hartle-Hawking proposal has no beginning in time

- the Vilenkin tunnelling proposal is similar in spirit but does have a beginning.

- unclear whether these proposals are well defined, and Hartle-Hawking appears to give wrong predictions.

Did the Universe Begin? IX: More about Imaginary Time

- a more technical explanation about the notion of imaginary time used by Hartle-Hawking

If you put all of the physics information together, the conclusion I would draw is that: We don't know for sure whether the Universe began, but to the extent that our present-day knowledge is an indicator, it probably did. However, as Carroll correctly says, we can also construct models where it doesn't have a beginning. Taking into account known results from geometry and thermodynamics, the most plausible such models are 1) spatially finite, and 2) have a reversal of the arrow of time (e.g. the Aguirre-Gratton model).

I also noted that models like AG still have a low entropy "initial condition" somewhere in the middle of time. One might think that this type of "thermodynamic beginning" still calls out for some type of explanation.

Then I wrote a more theologically-oriented post about whether the Hartle-Hawking no boundary proposal leaves any room for God to have created the universe:

Fuzzing into Existence

- short answer: yes, if you think of God as a storyteller, not a mechanic.

I also discussed the possibility of Reparameterizing Time; is it even meaningful to ask whether time is infinite or finite when you can change coordinate systems? In this post I also argued that the main theological question of whether the universe needs an explanation seems to me much the same whether the universe has finite or infinite time.

Now, let me make another observation about the tire swing. Although the weight of the evidence is that the universe probably had some sort of beginning—and even more likely that there was some sort of low entropy "initial condition" even if geometrically time stretches past before that—this cannot be said to be certain. There is always the possibility that new scientific data or methods could radically change our picture of the very, very early universe. Similarly, while a finite past seems more in accordance with traditional Christian theology than an infinite past, there appears to be no strictly logical connection between the two ideas, once the act of Creation is viewed in a more timeless, "authorial" way. Thus one might conceivably have a theist who thinks time is infinite, or an atheist who thinks time was finite.

Should the argument for God's existence really rest on such a slender foundation as the ultimate decision of physicists about Big Bang Cosmology? Well, one thing is clear. In ages past it didn't depend on it. Obviously, Sts. Abraham and Sarah, David and Solomon, the prophets and apostles, and all the men and women who followed in their footsteps up through the 19th century, including eminent scientists such as St. Faraday and St. Maxwell: these cannot have believed in God because of the Big Bang Theory, because—guess what?—nobody knew about it yet! What does the Bible say about these people?

Now faith is confidence in what we hope for and assurance about what we do not see. This is what the ancients were commended for. By faith we understand that the universe was formed at the word of God, so that what is seen was not made out of what was visible. (Hebrews 11:1-3)

Our belief that God is the Creator does not depend on the vicissitudes of scientific progress, the swinging back and forth of the tire swing (or is it accelerating?) It doesn't matter, because in this case we have a more certain source of knowledge than Science.

By faith! The skeptic may scoff here, and say that faith is belief without evidence, but that is not the definition used in the passage above. It says that faith is confidence about what we hope for, but do not see. Unless we identify sight (conceived broadly as anything which can be directly experienced in terms of our 5+ senses) with evidence (things which allow us to conclude something about the world)—an identification which would incidentally also make Science impossible—the passage does not say that the ancients were commended for believing without evidence. But the example of the biblical heroes does give some pointers about what type of evidence was relevant to them.

The ancients did not believe that God was the Creator because they had a detailed scientific theory about where it comes from. (Indeed, if we take our minds off Genesis for a moment and read the Wisdom literature of the Bible: Job and Psalms and Ecclesiastes and Proverbs, the Scriptures seem to emphasize more our lack of knowledge about the details of creation, then any detailed programme of events...) On the contrary, the ancient Jews and Christians knew God, by personal acquaintance as it were, and therefore knew him to be creative and powerful, mighty in word and deed. Thus they could take him at his word that he is the Creator of all that we see.

The glory of Creation does indeed point to the glory of the Creator, so that it is possible for ordinary human reasoners to come to know that there is a Creator intellectually. But this sort of Theism, by itself, isn't what Christians mean by faith. Once we come to know God personally, we learn the more important fact that we can trust him, and know with confidence that there is nothing in existence which does not depend on him.

And therefore, although we see in this world visible things emerging from other visible, material things, we know that ultimately their origin comes from "God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature" (Rom 1:20). He created everything through his Word, Jesus Christ, from whom we have come to know what God is like. This way of knowing does not seem to depend very strongly on the details of past, present, or future scientific knowledge.

One could definitely argue that the Bible teaches that there was a Beginning (whatever this means from God's perspective). For example, the quotation above from Hebrews speaks of the formation of the visible universe. But whether or not this fact has been revealed by God, it is not obvious to me that the most important theological aspects of Creation really depend essentially on time being finite, or even well-defined. (Admittedly, if you believe that time is infinite, it might be easier to slip into a false notion whereby matter exists independently of God, who is merely the Chief Organizer of the cosmos. That would be a heresy—a false belief which may seriously obstruct your ability to relate to God or others properly—but it does not follow necessarily from time being infinite.)

The main point of the doctrine of Creation, I think, is that God is real, and that everything else is derived from his power and will. We know this doctrine is true because we know God. Not because of the Big Bang, as natural as it is to connect the two ideas.

Heck of a series, Aron; really enjoyed it.

Carrol-Craig Debate*

You put Carrol-Chen =P

[Oops. Fixed. My neural network comes with an autocomplete feature, and I can't figure out how to turn it off!---AW]

Prof. Aron:

Thanks again and, Jack, that makes two of us regarding the series. I said back in August 24, 2104 in Slightly Less Random Links, I looked forward to seeing this series in book form, and I will add here, complete with the technical details. Understandably, that couldn't be packed in a blog for general readership..

TY

Jack, TY, thanks so much for your compliments.

But what makes you think I'm done with the series? :-) This was only a miniseries that has come to an end. I still need to say what I think of the Cosmological Argument, address fine tuning, and Carroll's specific arguments against theism! So save your book orders for later...

[Added later: Never mind the fact that I myself called it the "end of the series" at the beginning of the post itself...]

Regardless of any future blog posts, I too would LOVE to read a book authored by you that addresses scientific arguments against/for theism.

Aron, your summary of BGV above is badly misleading. There is nothing in BGV that says all past-directed geodesics have to end on the SAME singularity. And BGV allows comoving geodesics to be past-infinite. So we could have a situation where different past-directed geodesics end on different singularities, and the set of singularities marches backward infinitely in time.

So it's just false to claim BGV requires that "if the universe has a positive average expansion, it had to have a beginning."

Aron:

The Book would make a huge contribution to science and theology. I can wait.

(A) It would dispel a lot of common myths about these two approaches to understanding how did things begin and the way thing are. If would show the two are not undivided but complementary.

(B) The finely tuned and intelligent character of the world we live it opens up many interesting questions and people want both well-reasoned and reasonable expositions.. Science can only go so far in providing a narrative but then we need additional insights from theology and religion. But we need to see the science and to be convinced of the limitations.

(C) And it would be a natural extension to include in the Book a few chapters on quantum theory, the notion of indeterminacy versus determinacy, the fact that the quantum world seems to obey a logic of its own, and how the mind enters our understanding of this "weird" world (as some describe it). A discussion of quantum theory necessarily would include the Many World Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics . And all of this takes us to the question of whether the human mind transcends the physical universe and, if that is true or plausible, then an an ultimate mind, which is God, is that more convincing. So we are back to where we started on the question of creation and the beginning of time.

TY

Welcome to my blog, Robert.

Of course the details you're looking for are in the post I linked to, but you're right I could have done better on the summary. I meant that there has to be a beginning somewhere. I've adjusted the summary. For the record, the original summary Robert was responding to read like this:

- if the universe has a positive average expansion, it had to have a beginning

- implies that inflation had to have a beginning in time

- can evade theorem by a "bouncing" cosmology where the universe contracts and then expands

and I have modified it to read:

- if the universe has a positive average expansion, then "nearly all" geodesics cannot be extended infinitely to the past

- implies that inflation had to have a beginning in time, at least in some places

- can evade theorem by a "bouncing" cosmology where the universe contracts and then expands

Aron,

I have a question that I had meant to ask you a while back concerning the AG model's avoidance of the BGV theorem. It seems to me that there are two possible ways to interpret an AG-like bouncing spacetime:

(1) Do so with a monotonic arrow of time running from and the "bounce" occurring on a null hypersurface. If this option is preferred, then wouldn't that mean that the Second Law of Thermodynamics would be violated for an infinite temporal duration from

and the "bounce" occurring on a null hypersurface. If this option is preferred, then wouldn't that mean that the Second Law of Thermodynamics would be violated for an infinite temporal duration from  as entropy decreases consistently during the contracting epoch?

as entropy decreases consistently during the contracting epoch?

(2) Do so with dual AoTs, both of which running away from a spacelike hypersurface at where the "bounce" occurs. If this option is preferred, then wouldn't this amount to the spacetime not in fact evading BGV because then what we would have is two different spacetimes, each of which always being in an expansion phase—and thus each of them satisfying the condition

where the "bounce" occurs. If this option is preferred, then wouldn't this amount to the spacetime not in fact evading BGV because then what we would have is two different spacetimes, each of which always being in an expansion phase—and thus each of them satisfying the condition  ?

?

As always, thanks in advance for your time.

Please feel free to correct my LaTeX coding with the correct start/stop indicators.

[Done!--AW]

Jack,

As you say, there exist two different types of AG models, one where the arrow of time reverses on a null hypersurface, and the other where it reverses on a spacelike hypersurface. These correspond to two different ways of slicing de Sitter space, and they would lead to physically distinct spacetimes once you include non de Sitter phenomena such as vacuum decay, matter and/or black holes. There is a diagram of these two choices in Fig. 1 of this paper.

In either case, the Second Law is "violated" in the contracting phase, in the sense that entropy decreases with time. But that's just another way of saying the arrow of time is reversed during the contracting phase. We could redefine the Second Law to say that entropy always increases away from the special slice.

In case (1), I'm not sure what you mean by . What time coordinate are you using? In case (2), the spacetime has just one connected component, so that is why we call it a single spacetime instead of two different spacetimes.

. What time coordinate are you using? In case (2), the spacetime has just one connected component, so that is why we call it a single spacetime instead of two different spacetimes.

Aron,

I apologize for my mental lapse in my description of case (1); I did not mean to attribute the time coordinate to this case.

to this case.

Just to make sure we are on the same page with our terms, would you mind answering the following questions:

1. Do either of the physical interpretations of the AG model presuppose any particular philosophical theory of time? More specifically, must one ascribe to the B-Theory in order to properly interpret the AoT reversal?

2. When you speak of the "arrow of time [being] reversed during the contracting phase," are you saying nothing more than just that entropy is decreasing during this phase? What I mean is, you don't in any way mean to imply that there is a reversal of ontological time, right? In other words, even though the AoT reverses in the sense that entropy is decreasing, do you still hold that the time coordinate varies monotonically from and that there is a non-reductionistic arrow of time that goes from past to future and is not determined by entropy increase?

and that there is a non-reductionistic arrow of time that goes from past to future and is not determined by entropy increase?

There is one final issue that I would like to raise. I warn you, even though it will at first appear to be the same argument that I made in our previous, lengthy discussion—the one in which you had 47 final comments :-) —, I assure you it is not. I will lay it out formally so that you can easily spot any false premises or invalid reasoning on my part.

First, let me state that the type of spacetime of which we will be discussing is one that obeys the condition . For simplicity's sake, let us also assume that the rate of contraction is constant; that way I don't have to keep writing "on average."

. For simplicity's sake, let us also assume that the rate of contraction is constant; that way I don't have to keep writing "on average."

1. If we trace the worldline of a non-comoving geodesic observer , we will find that her motion relative to comoving test particles

, we will find that her motion relative to comoving test particles  in a contracting congruence will be processionary.

in a contracting congruence will be processionary.

2. If (1), then the measure of relative velocity between

between  and each

and each  will increase successively by some nonzero value.

will increase successively by some nonzero value.

3. If and

and  are in processionary motion for an infinite temporal duration, then

are in processionary motion for an infinite temporal duration, then  will eventually observe an infinite number of

will eventually observe an infinite number of  .

.

4. If (2) and (3), then there will be an infinite number of increases in the value of .

.

5. If (4), then will eventually reach an infinite value.

will eventually reach an infinite value.

Thus, if the argument is sound, then it leads to absurdity: relative velocities cannot reach infinite values. But it would also therefore follow that an infinite interval of prior contraction is impossible.

Please don't yell at me for yet another lengthy post :-) It's just something that I've been thinking about and I was wondering what you thought. Thanks.

Jack asks:

I don't think there's a strict logical contradiction with the A-theory, since the A-theorist could just say that entropy happens to be decreasing relative to the "true" direction of time flow.

However, it might be possible to make the A-theorist feel a bit uncomfortable by asking what happens if there are conscious beings who live "backwards in time" in the period where entropy is decreasing? Would they feel anything different than we do? If they do feel something different, how is this possible given that the laws of physics are (almost) the same in the backwards direction? If they don't feel anything different, how do we know we aren't living backwards in time ourselves? What reason do we have to believe in A-theory if it is disconnected from our actual experience of time?

I'm talking about the "thermodynamic arrow of time", so yes I just mean that entropy is decreasing during this phase (due to there existing special low entropy final boundary conditions, but no special initial boundary condition).

As a B-theorist, I'm not sure that I believe in any such thing as "ontological time", apart from whatever structures are defined using geometry, thermodynamics, and the laws of physics.

A time coordinate is just an arbitrary label. You could make a time coordinate which goes from , or a time coordinate which goes from

, or a time coordinate which goes from  , or one which goes from

, or one which goes from  , and they could all be describing the exact same universe. It's just an arbitrary labelling scheme for spacetime points.

, and they could all be describing the exact same universe. It's just an arbitrary labelling scheme for spacetime points.

One game we can play which does not depend on coordinates is this. Suppose we have a Lorentzian spacetime manifold; this is the type of geometry used in GR, where each point has two lightcones coming out of it. But at any given point , we don't know which one to call the "past" or the "future" lightcone. Let's says we arbitrarily decide which one is which at the point

, we don't know which one to call the "past" or the "future" lightcone. Let's says we arbitrarily decide which one is which at the point  . Then we can extend this to the rest of the spacetime by the following technique: for any other point

. Then we can extend this to the rest of the spacetime by the following technique: for any other point  , connect the two points

, connect the two points  and

and  by some curve. Then by "parallel transporting" the lightcone from

by some curve. Then by "parallel transporting" the lightcone from  to

to  , we can figure out which cone is past/future at the point

, we can figure out which cone is past/future at the point  . Thus we have labelled the entire spacetime with a notion of past vs. future, up to a single arbitrary 2-way choice.

. Thus we have labelled the entire spacetime with a notion of past vs. future, up to a single arbitrary 2-way choice.

(There are a couple ways in which this construction might go wrong. First, if the spacetime has 2 or more disconnected components, then there is no way to connect points on different components and therefore we have to choose the "bit" of information separately for each component. But you might want to call this several spacetimes, rather than a single spacetime. Secondly, on some exotic manifolds, if you go around a closed curve you might end up flipped in time. On "non-time-orientable" spacetimes like these, there is no way to define past vs. future. But these are typically regarded as physically unrealistic solutions to General Relativity and ignored.)

Regarding your new argument, I'm not sure what you mean by "processionary". I'm not sure I've ever heard this word before. Also, I don't think your argument is valid when you proceed from (4) to (5). A quantity can increase an infinite number of times without ever reaching infinity, if it doesn't increase by the same amount each time. That is, the sum of an infinite series of positive numbers can be finite.

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/processionary

I said "For simplicity's sake, let us also assume that the rate of contraction is constant; that way I don't have to keep writing 'on average.'" Therefore, it will increase by the same amount each time, right?

Jack,

I was indeed able to find the disctionary.com definition of "processionary", but it is just "of, related to, or moving in a procession". That doesn't tell me what is processing from what, or along what. (That's the hazard of turning verbs into nouns in technical writing---one loses all sense of who is doing what to whom). And what do you mean by procession? Do you mean that some quantity is monotonically increasing or decreasing? If so, you should just say that.

No. The "rate of contraction" is the rate at which space is contracting. (I assume you meant constant decrease of spatial length per unit length per unit time, which would correspond to an exponential decrease of the scale factor of the universe with time, since that's the relevant definition of uniform contraction for the BGV theorem.) But for step 4 of your argument, you need for to be increasing by a uniform amount. Since

to be increasing by a uniform amount. Since  is a different quantity from the expansion of the universe, it does not increase uniformly, just because the expansion increases uniformly. The amount by which

is a different quantity from the expansion of the universe, it does not increase uniformly, just because the expansion increases uniformly. The amount by which  increases depends not only on the current expansion of the universe, but also its current value.

increases depends not only on the current expansion of the universe, but also its current value.

I so happy to have found your blog page. I’ve wanted to pose some cosmological questions to someone who has a thorough understanding in this field of study. After going through a number of your blogs I have to admit that I greatly appreciate the scientific acumen and expertise you’ve demonstrated.

I’ve been going though a number of your old post, mainly since the Carroll/Craig debate, in the hopes of seeing whether you may have responded already to a question I have. You mention in your Comment Policy that it’s okay to place new comments in old blogs which correspond somewhat to the comments/questions raised. I haven’t seen my question raised elsewhere as of yet, so I’ll pose it here.

It seems to me that there is a very simple thought experiment, maybe it’s too simple to call even that, which shows that an on average expanding universe cannot be past eternal. But I haven’t noticed others presenting this as evidence. Could you suggest any deficiencies for the following argument?

With an expanding universe, as one looks back in time, the universe will become continually smaller. It will eventually reach a point at which it cannot become any smaller. We cannot conceive that it can become continually smaller and never cease to do so. Physical processes will eventually alter this contraction into the past. If this shows an expanding universe must have a beginning, I can only think of the following as a serious defeater.

As we go back in time, the universe should eventually enter a quantum gravity regime (I hope I’m using the correct terminology). Now is it that something simply cannot become smaller than a Planck scale or is it that we just do not know what will happen at this size? If the former, then clearly there must be an origin to an expanding universe. If the latter, then we are cast into the unknown and this thought experiment fails to demonstrate an absolute origin.

If it is merely a problem of entering a quantum era that makes this scenario powerless to prove an origin to the universe, I wonder why this has not been offered as an argument when quantum issues were not being considered. The BGV theorem, for example, supposedly shows that an on average expanding universe must have a beginning so long as quantum mechanics does not apply. Well, if we preclude quantum mechanics from consideration, wouldn’t it be simpler to appeal to this thought experiment rather than to the BGV to show that the universe is not past eternal?

Welcome to my blog, Dennis.

So one crucial thing the BGV theorem does is to provide a mathematically precise definition of "expanding on average" even in spacetimes which aren't homogeneous and isotropic at one moment of time, in order to prove the result in such cases. Whereas your argument, being cast in the form of words, isn't really precise on what the meaning of "size" is. Since concepts of space and time are very tricky in general relativity, one wants to be careful here.

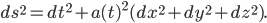

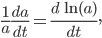

But suppose for simplicity we restrict to the case of a homogeneous and isotropic universe. If we also suppose that space is infinite and "flat" at one moment of time (meaning that it has the geometry of a Euclidean space, then the most general metric we can write down is:

This is just like the metric of Minkowski spacetime, except that distances at a given time are made bigger or smaller by the "scale factor"In a classic FRW big bang model, at a finite time in the past, and it doesn't make sense to talk about times before that. But suppose that instead we set

at a finite time in the past, and it doesn't make sense to talk about times before that. But suppose that instead we set  to be an exponentially increasing function of time,

to be an exponentially increasing function of time,  being a constant. This would correspond to a scenario of "eternal inflation", but in which the inflation goes back infinitely far to the past as well as to the future (normally that term "eternal inflation" only refers to inflation lasting forever to the future...). This spacetime would go back forever to the past. In such a universe, the average expansion, in the sense of rate of expansion per unit length, defined as

being a constant. This would correspond to a scenario of "eternal inflation", but in which the inflation goes back infinitely far to the past as well as to the future (normally that term "eternal inflation" only refers to inflation lasting forever to the future...). This spacetime would go back forever to the past. In such a universe, the average expansion, in the sense of rate of expansion per unit length, defined as

would be constant, and thus the universe would be the same at all moments of time, despite the fact that it is always expanding (this is possible because the universe is infinite).The universe described by this metric appears to evade your argument, since its "size" is infinite at all times. Yet it still in a sense has a beginning, even though it also goes back infinitely in time. How is this possible? The answer is that some timelike goedesics (those which are at rest relative to the expansion of the universe, that have constant ) go back infinitely far in time, but all the rest of the timelike geodesics end up exiting the spacetime geometry I wrote down in a finite amount of proper time to the past. The BGV theorem says that this conclusion continues to hold even if we drop the assumptions of homogeneity and isotropy, so long as the "average expansion" (in a new sense defined in their paper) is positive.

) go back infinitely far in time, but all the rest of the timelike geodesics end up exiting the spacetime geometry I wrote down in a finite amount of proper time to the past. The BGV theorem says that this conclusion continues to hold even if we drop the assumptions of homogeneity and isotropy, so long as the "average expansion" (in a new sense defined in their paper) is positive.

The latter. Some people have indeed suggested that distances shorter than a Planck distance wouldn't make sense in a theory of quantum gravity, but such statements are speculative until we have a confirmed theory of quantum gravity.

And yes, "quantum gravity regime" is correct terminology.

Wow. I never imagined the issue was so complicated. Thanks Aron.

On second thought, I suppose I should have imagined that the issue is this complicated since it took an entire theorem and many years to verify it. Or is "verify" the correct word in this case? The BGV is not empirically verified, that is, verified by observation, but I don't think cosmologists consider it in any way questionable, do they?

Dennis,

A theorem is, by definition, something that has been proven mathematically. Thus a theorem itself does not require empirical verification; however, whether a theorem applies to a given situation does have empirical elements. If a theorem takes the form "if x then y", or "all x's are y's", then just because the theorem is true does not mean that x is in fact the case in a physical situation.

The BGV theorem applies to any classical, Lorentzian metric which has the property of having positive "average expansion" as defined in their paper. The theorem is a purely "geometrical" fact in the sense that it doesn't require the Einstein equation or anything like that to hold. On the other hand, if the universe is sufficiently quantum that we can't write down a definite spacetime metric, then the BGV theorem is inapplicable to the situation.

(An analogous statement might be true in quantum gravity, but we couldn't possibly prove that in our current state of understanding.)

Are you done with the series? (It's been epic), but there's, a second argument for an eternal universe in the Carroll-Craig debate by Carroll. Which I think you might have addressed in the arXiv paper Craig referenced. But it concerns entropy, that the best models for solving it are eternal with only a thermodynamic beginning. (Like how you describes the Hartle-Hawking model). Yeah, I pay attention and learn from your posts! :D

I looked it up and all I could find was this short comment on the argument by Guth: https://edge.org/response-detail/25538

Andrew,

Yes, the series on "Did the Universe Begin?" is over. I'm not sure what "second argument for an eternal universe" you are referring to. I discussed eternal models with low entropy in the middle in part V.

Aron, would you mind if I stated the following on my web page and then reference this page?

“Cosmologist Aron Wall, after assessing the various lines of evidence, also concludes that the universe more probably had a beginning than not.”

I’m fully aware that you think this is a very weak conclusion since you mention that it seems that the evidence can so easily swing from one conclusion to another and that our faith should be based on something stronger. I agree, but I also think that there is some evidence here, some probability claim can be made, and so this would have power for a cumulative case argument. This statement seems to me to be your opinion from what you’ve concluded above. But if you think I am misstating your view or that it needs more qualification, or if you think I should not say this at all, please tell me. I’m aware that in his debate with Carroll, Craig cited you’re opinion on some point and with his quotation or summary statement it sounded as though you were making a claim that was stronger than you intended. So I’d like to ask you first rather than make the same mistake.

Dennis,

The statement is fine, except that I think it would be more accurate to refer to me as a physicist rather than a cosmologist, since unlike e.g. Alex Vilenkin or Alan Guth, most of my actual research is not in cosmology.

Pingback: Cosmology, philosophy and theology – what more could you ask for? | the Way?

Aron, since the completion of this mini-series a new paper was published and I would love for you to comment on it. Or, if you have commented and I've missed it - let me know.

The paper is "Cosmology from quantum potential" by Ali and Das.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1404.3093v3.pdf

Pingback: Christianity and Science | Evangelicals in the Episcopal Church

Hello Mr. Wall , I was wondering, if I could have your permission to share some of your articles on our Facebook group without adding , subtracting or modifying anything for Educational purposes, would that be ok with you sir ?

Thanks

Best regard

Abu Muhamed Alee

Yes it is fine as long as you give proper attribution. I would also appreciate it if you would also include a link back to my blog, in case people are also interested in my other articles.

As a layman I can't say I fully comprehend this series. (I always performed better in history class anyway.)

Based on what I understand, it does seem that the above conclusion is pretty damning in regards to the cosmological argument. Am I understanding you correctly?

Efraim,

The Cosmological Argument is not really a single argument but rather a family of arguments. The majority of such arguments do not refer to a beginning of time at all, but rather to other features of the universe such as its contingency or changeability or causal dependency.

There is one particular type of cosmological argument, the so-called "kalam argument", which argues for God on the basis of the Universe having a beginning. IF you try to support the claim that the Universe began using modern scientific cosmology, and IF you want the conclusion of this argument to be absolutely certain, then yeah that won't work. But there are lots of other versions of the Cosmological Argument that don't depend in any way on the Big Bang (although they may have other issues).

If you want to learn more about the traditional approach to these arguments, you might start with St. Ed Feser's blog. If you're curious about my own reflections on the sorts of arguments I find helpful, then try my series on Fundamental Reality.

Thanks for responding.

I was indeed aware that not all cosmological arguments are the same (Leibniz comes to mind). I'm just wondering why WLC speaks about the finitude of the past like it's a cold hard fact!?

Perhaps because he's approaching the subject as a debater, rather than as a scientist?

People who approach the intellectual world primarily from the standpoint of debate, acquire a habit of feigning more certainty with regard to their chosen positions then they ought to have---I say feigning, but the most effective method of doing this is to start by convincing yourself to be more confident than you ought to be. (Although paradoxically, in some cases this can prevent the debater from coming to really know the best grounds for knowledge, and hence deprives them of true certainty and knowledge.)

That's quite disheartening!

Indeed, he does at times seems to be focused on winning if anything else.

Let me moderate the cynicism in my remarks somewhat. Benevolent and wise people can be subject to certain temptations, that don't necessarily apply to people beneath them, who aren't really trying to accomplish what is good. St. Craig rightly cares about people coming to believe what is true, and he has always been perfectly transparent about what his own motivations for debating are.

Still, there is an moral hazard displayed here. You and I should learn from it, and try to do better if we can.

St. Mark Strange left a couple additional antagonistic comments, in response to my critique of St. William Lane Craig.

Since he obviously isn't interested in an actual dialogue (or he would have engaged with my detailed rebuttal of his original complaint), I have deleted his recent comments.

Anyone who tries to be a public intellectual must be prepared to sometimes face criticism for their opinions. But there is a limited amount of abuse I am willing to put up with on the blog that I moderate---from a person who thinks I am insufficiently respectful to my fellow Christians, but is unwilling to model that respect in his own comments. Mark Strange is therefore BANNED from posting on this blog in the future. If he wishes to put in his two cents, he is free to start his own blog.

Hello, Aron

I would like an advise. I have an special interest in space time, particularly time. Which career path should i choose? Should i stick to philosophy of time or really get serious with quantum gravity or general relativity? Thank you for the blog.

Hello,

What do you guys think of this bouncing universe model? https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.05133

St Wall: It was a great debate and enjoyed your assessment of it here and on capturing Christianity. Thanks for the cartoon - it made me laugh.

"Since he obviously isn't interested in an actual dialogue (or he would have engaged with my detailed rebuttal of his original complaint), I have deleted his recent comments." Where is the detailed rebuttal, where is Mark's comment - how can we know if his comments are beyond the pale or even what the rebuttal rebutted? I know Mark and he is rarely rude - was Aron outmatched? Not very open of you Aron. I would have expected better.

Efraim Cooper

"I was indeed aware that not all cosmological arguments are the same (Leibniz comes to mind). I'm just wondering why WLC speaks about the finitude of the past like it's a cold hard fact!?"

Craig has never said that the finitude of the past is a cold hard fact from the physics side. Please read what he actually says in his published work. His arguments are primarily philosophical with the physics used as additional confirmation. The time recent collections on the Kalam by Routledge is a good start.

Hello Aron,

This is quite a bit off topic but I wasn't sure where to best post my concern and question. I hope you don't mind that I post it here since this looks to me to be the last OP you've made. I know you're pretty tied up with numerous obligations so I hope you do find some time to look at this. But if you can't, I would understand.

[I would prefer if you leave your question on a topical post even if it is old. I have therefore taken the liberty of moving it myself to the "Did the Universe Begin? series.---AW]

I discussed some questions regarding science and religion with you a number of years ago on your blog page but I haven’t been on your page since then. I recently pulled it up again but it looks as though you haven’t been actively posting articles on the page for maybe half a year, though I see you have still been corresponding to your readers’ questions and views. At the time I first began posting on your blog the big discussion was the debate between William Lane Craig and Sean Carroll. I believe in the end after talking about all of the facets of the various issues and arguments, your conclusion was that the universe probably did have a beginning.

A few years ago I wrote an essay for my own web page attempting to summarize the best scientific evidence for theism focusing on the evidence for a beginning of the universe (U). I don’t believe much new has come out since the debate that would affect your earlier conclusions or my own. But I’ve recently looked at the old arguments again and I’ve begun to notice a problem I hadn’t seen earlier. This came about by thinking of Penrose’s Conformal Cyclic Cosmology (CCC) model. I had emailed you about five years ago concerning the CCC and you gave me some comments and a link to some other comments you made on your blog (http://www.wall.org/~aron/blog/fixed-problem-with-previous-post/). At the time I felt the issue was basically solved. Only in my recent reevaluation do I see a serious problem for arguments for a U with a beginning.

As I understand it, the CCC is a kind of cyclic U model with a new Big Bang originating at the end of the lifetime of each U (each eon) and this continuation of rebirths of new U’s has no beginning and no end. Since these cycles have no end it also answers the fine-tuning question. With slight variations in each U, eventually a U will occur which has all of the characteristics that allow for life and all of the chance events will take place so that life and evolution will occur and produce self-conscious and morally conscious intelligent organisms.

Sabine Hossenfelder points out that there are some patterns in the CMB, the Cosmic Microwave Background map, that would be expected if it were true but they are also what we would expect if the accepted inflationary model is true. So any empirical evidence is inconclusive. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jl-iyuSw9KM). But perhaps the biggest problem is that it requires some conjectured exotic physics which presently have no verification. This is the criticism of apologists of the stature of W L Craig and Stephen Meyer (https://www.reasonablefaith.org/media/reasonable-faith-podcast/dr-craig-responds-to-youtube-mentions). Hossenfelder also says that the CCC has to get rid of the Higgs bosons at the end of each eon, and we don’t know how it could do that. Might someone just conjecture more possible exotic physics, physics we currently know nothing about, to get rid of them?

Thinking of this model and Craig and Meyer’s apologetic response, I see a serious problem. When Craig could appeal to Vilenkin’s strong statement that the U had to have a beginning, Vilenkin was basing his claim on the known nature of the U and some of the best and most reasonable assumptions about the nature of the U. I take it that the CCC is a way around the BGV so long as its highly conjectural exotic physics is possibly true. So it looks as though the BGV at one time offered good reason to believe the U has a beginning. It was positive evidence; I suppose we can say it is based on empirical evidence. The problem is that once someone can construct something like the CCC and propose physics that will override the BGV, then are they not offering evidence which is on the same level as the theistic argument from a beginning of the U? The theistic argument is that if we have a creator who could cause the U to come into being, then that is the best explanation for a U such as we find it now, if we find that it had a beginning. But likewise someone could say that if we have certain laws of physics that will allow the U to have never had a beginning or end, then that would equally explain the U as we find it now. That would defeat the evidence that it had a beginning. Conjecturing God or conjecturing exotic laws will equally explain what we now know, so what grounds do we now have to claim one over the other?

At the moment this thinking looks to be a game changer for me, but not the kind I would hope for. If A and B can equally explain C, and we have no other evidence for either A or B, then A cannot be preferred over B or B over A. If T (theism) and L (possible natural laws of which we have no other evidence) can equally explain W (the world or universe so far as we know it), then we cannot prefer T over L.

I do have other reasons for my belief in God, some philosophical and historical and some experiential, so to lose these particular scientific arguments for God’s existence would not harm my faith. But after so long believing that these scientific arguments are good additional arsenals for belief, I would find this a great loss.

I hope I have misunderstood some of the scientific claims of the BGV or CCC or some of the logic for the grounds for scientific belief. Let me know if you think I have.

Dear Dennis,

1. Let me start by saying that in my view CCC is not a plausible hypothesis at all. There are several scientific problems with it, ranging from the difficulties in deciding what it means, difficulties in fitting it to the rest of physics, the fact that it appears to violate the Second Law etc. You can find some of my previous criticisms in earlier comments, for instance here. I don't know any physicists who take it seriously, and I doubt it would have received any traction if it had been proposed by somebody less eminent than Penrose.

Prior probabilities matter as well. Physics is not just about matching observation, but also about models that are elegant and can be made mathematically precise---and the CCC fails badly on these latter criteria. (Although, I don't see any way of you coming to know this without deciding to trust me, or some other cosmologist like Sean Carroll, on this point.)

2. Having said all that, I'd rather put the focus of my reply elsewhere, in terms of your own spiritual journey. I'd like to zoom in on the following paragraph, which I think diagnoses the emotions behind your "disturbing question" [as you call it in the subject header of your parallel email to me]:

Since I respect you, and your spiritual maturity, I will be far more blunt with you then I would be with another inquirer. You have NO RIGHT to feel this way about any particular argument for God's existence. Certainly not one which, as you plainly admit, is not a necessary prerequisite for your own faith. It seems like you are conflating your feelings about an idea about God, with the feelings that are properly directed towards God himself. (If, instead, you were treating this idea with the appropriate intellectual lightness and playfulness---the same as any other philosophical argument---then you would not feel a sense of dread at potentially losing this argument with yourself.)

Since you yourself confess that you don't need this particular idea in order to be a Christian, it follows that God has every right to take it away from you. The Holy Spirit is responsible for your spiritual journey towards God. And so, if the Spirit sees that you are clinging to an idea that is no longer helpful to you (at your current stage of development) then the Spirit, out of love, must seek to purify your thoughts about God, by purging any conception which is unworthy of him (smashing the idols). Precisely because you are clinging to a certain idea too much, God has to take it away from you. In doing so, he is not drawing farther away from you---as it might first appear---but in reality approaching closer. Because the purging of wrong or inessential ideas, is a necessary step prior to filling your mind with more worthy thoughts about the divine. You are, in fact, in the hands of a loving Father, and thus it would be better to react to this purging of your mind with joy than with dismay. Since you know that he only takes things away, in order to fill you with better things.

According to Hebrews 12, "all of creation will be shaken and removed, so that only unshakable things will remain." If an apologetics based on controversial quantum gravity claims can be shaken, then it probably will be, and so you'd best not get too emotionally invested in it.

The same applies if your concern was being able to use this argument in apologetics directed towards others. If this is not the real reason why you belive, maybe it is a tactical error to put it front-and-center in debates with others? There's a danger in online professional apologetics, if we get sufficiently invested that we fail to learn and grow. You SHOULD start to feel a bit differently about some of the things you've posted as the years go by. If you don't, it means you haven't been learning anything, and you wouldn't want that!

Imagine completing the following sentence:

"Jesus died on the cross for me, so that I can __________________________________"

Are any of the top 50 best completions: "have the correct opinions about quantum gravity?" It seems unlikely to me that this is the case. So why all the fuss and bother? The Kingdom of God isn't recruiting people to steady the Ark of the Covenant!

I am in no way suggesting that God's glory isn't visible or manifest in Nature. Of course it is. Once you are past this unpleasant process of purification (and have integrated the resulting insights into your spirituality), no doubt you will again perceive this perennial truth, in some new way. But that doesn't mean that our faith rests on a particular interpretation of 20th century Big Bang Cosmology. If the Big Bang theory were God's primary way of revealing himself to human beings, then how come nobody prior to the 20th century was in possession of the relevant evidence? When the 318 bishops of Nicea declared: "I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of all things visible and invisible", this includes the cosmic microwave background, but I suspect that if you asked them for their rationale, that would not have come up. If the sole reason to posit Theism was to explain the details of the CMB radiation (as one of your paragraphs absurdly seems to suggest, even though I know you know this is not the case) then I would actually agree with the skeptics that the deduction is uncertain, and that new updates in cosmology might well undermine Theism. But the assumption is misguided. If God comes to you in a whirlwind and asks you: "Where were YOU when I laid the foundations of the universe?", are you going to quote the personal opinions of Vilenkin or Hossenfelder or Penrose or Hawking or me back to him? Or are you going to acknowledge that (like Socrates) you know nothing, but only wish to know?

As penance for your presumption, I suggest taking the time to meditate on the 131st psalm, reciting it out loud 10 (±2) times. Some Christians claim to have a "life verse" that particularly speaks to their whole way of life. v1 feels more like my anti-(life verse), which I guess is why I'm constantly in the position of having to explain it to others. Because what people want to hear from a Christian physicist, is not the same as what they need to hear.

professor Aron,

just how plausible are cyclic universes as an explanation for the fine tuning, such as the Steinhardt-Turok model? It seems they, as a class, constitute plausible model in alternative to the multiverse. Whether they have necessarily a beggining would be another question entirely. Additionaly, how do cosmologists see the Smolin's cosmological natural selection model? Can it be eternal and can it explain the fine tuning?

I wish best regards.

I do have to say thank you for your brotherly concern. Paul said we are to teach and admonish each other (Col 3:16) and I would add that this is especially true when we feel there is a strong need. But I’ll say more about this next time.

But let me get back to the logical problem that does still bother me. It bothers me because it affects how we see so much of our reasoning concerning the sciences and because I’m not sure I’ve been able to convey to you exactly what my concern amounts to. I earlier used Penrose’ CCC model, but I offered it as merely an example. Penrose’ model was just the catalyst that got me to see this logical problem. As a different example, think of the simplest forms of the fine-tuning argument for theism. Before talkiing about this argument, let us assume that we have no other evidence for theism. Let’s see how this argument fares if this were the only reason one might have for belief in theism. (I’m sure many atheists and agnostics have been in precisely this position when they first heard of some form of the fine-tuning argument.) The argument says that we have discovered in nature that the values of certain constants of physics and other conditions must be precisely what they happen to be in order for us to have a life-permitting universe that allows for the existence of embodied moral agents. The strength of gravity, for example, must not vary by more than one part in 10^60 (assuming the other constants are not varied from what they are now) or no life-permitting universe could form. The universe would have exploded too quickly for stars to form or collapsed too soon for life to evolve. We argue to theism by saying that an intelligent agent in control of this value can make it precisely what it is to allow for this life-permitting universe but all other explanations are extremely improbable (given the one chance in 10^60). So T (theism) can account for a life-permitting universe (LPU) but nothing else adequately can. But suppose we hypothesize L, a possible natural law of which we have no other evidence? L might produce an LPU by producing a multiverse (MU). We could have all the differing universes out there now as just a brute fact or we might have them produced sequentially like the CCC and other models claim. If both T and L are equally possible so far as our knowledge is concerned, how can we choose between them? In fact we might simply hypothesize MU, that there is a multiverse of either an infinite number of greatly and slightly differing universes or a sufficiently high number of such universes for one of those universes to eventually produce embodied moral agents. How can we rightly choose between T and MU? At the moment the only way I can see to choose between T and MU is by appealing to something like Occam’s razor: T is simpler than MU. But maybe if the choice is merely between L and T, it would be harder to see that the razor might apply. How do you think we should reason in cases like this?

Dennis,

Thanks for explaining more clearly where you are coming from.

1. As a slight response to your specific question, one could certainly note that it is hard to come up with any formulation of L that doesn't look wildly different from the laws that we are accustomed to. In particular (as I argued in my talk on Fine Tuning) if we demand that the laws take the form of a local field theory (as most naturalists would want) then it is very hard to explain the fine-tuning of e.g. the cosmological constant in any such reductionistic picture.

(I would note in passing that the "strength of gravity" isn't really the right way to think about fine-tuning. In particular, as I said in the talk, it is important to only consider constants without units, e.g. the cosmological constant in Planck units. Your 10^(-60) might possibly refer to one of the commonly posited fine-tuning examples I don't believe is valid---the initial rate of the expansion of the universe---but it doesn't matter much because the cosmological constant fine tuning really is at least this good.)

But, this only ameliorates your objection. If you were under the impression that the flagship numbers like 10^(-60) or whatever represent the actual strength of the fine tuning argument in Bayesian terms, then unfortunately this is simply not the case. These numbers are the chance of explaining fine tuning with "We just got lucky!" But, once the number gets tiny enough, any sensible skeptic responding to a fine-tuning argument is instead going to look for the most probable loophole that gives them a way out, and it is rational for them to do so. The actual strength of the fine-tuning argument is proportional to the degree that they have to adopt unlikely assumptions, in order to wiggle out of the argument, and such counters are almost always going to have a probability that is much closer to order unity, than it is to 10^(-60). (This is in fact true for every argument involving low probability events---not just this one! This is just how epistemology works, so it is unavoidable.)

2. More generally, I think I am inclined to reject the rhetorical framework of your question. I don't think that you should ever, in any apologetic context, concede that fine-tuning is the only good argument for Theism. From a philosophical point of view, Theism is justified based on a cumulative case, involving multiple arguments, and it is important to make it clear that this is the case. (Of course, in a particular article, one might discuss only one particular argument, to keep the scope of the discussion from getting out of hand, but this is a limitation of the format, and shouldn't be confused with what a comprehensive case would look like.)

I think asking for one single argument to take somebody all the way from skeptical atheism to committed theism, is asking more than can be reasonably expected from a single argument! As the Good Book says: ``Any matter must be established by the testimony of two or three witnesses.'' In Bayesian terms, one argument is needed to establish that the prior probability of Theism is not tiny. And a second argument is needed to establish that Theism explains some specific datum much better than Naturalism does.

Or, when the police catch a man, one argument is needed to tie him to the crime scene. And a second argument, such as a DNA test, then establishes guilt. You can't just randomly DNA test everyone in a big city; this dramatically increases the chance of a false positive. Yet it should be noted, that an argument that suffices to establish that sombody is a suspect, need not be free from doubt taken in isolation! If a woman is found dead in an alley, then "her jealous boyfriend" and "the suspicious dude that was found running from the crime scene" both immediately become suspects (i.e. non-tiny prior probability of guilt). Obviously no reasonable jury would convict them on these factors alone, without further evidence. And yet, a positive DNA match with one of these two suspects, could well establish guilt beyond a reasonable doubt! Which would not have been reasonable, if you found a match in a DNA database of 100,000 previously convicted criminals who weren't in any other way tied to the victim. And the same is true of apologetics. It is still quite valuable to present an argument that should make a person suspect that Theism might well be true, even if that argument isn't watertight taken in isolation. But, if you present it as if it were 100% watertight, no loopholes possible, than you are opening yourself up to attacks that wouldn't be possible if you limited your rhetorical aims to a more modest conclusion.

Here I am speaking of reasonable skeptics. For unreasonable ones, a more appropriate saying would be: ``A man convinced against his will, is of the same opinion still!" One characteristic of a hostile audience is that it is impossible to build a cumulative case for them. They evaluate each argument completely on its own, and try to find any reason whatsoever to dismiss it. Then, their evaluative state goes back to a background of "there is no evidence for the invisible dragon, extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof, Russell's teapot!" when evaluating the next argument. Such a person, who behaves as if he has no memory, cannot be convinced of anything. Or said another way, it isn't your job to convince anyone in the heat of the moment! But only to say things that might, later on, give them the ammunition to convince themselves.

3. Convincing people intellectually isn't the most important thing in any case. The more important thing is whether somebody's will is oriented towards or away from God. No argument (taken by itself) can change that, even if it might sometimes produce an environment more conducive to repentance. This speaks to the limitations of apologetics in general. A lot of neurotic tension surrounding this subject arises because people confuse the goal (salvation of souls, which can be done only by God) with a particular means (intellectual and rhetorical persuasion by specific arguments) and forget about all the other stuff that is usually more important. For this reason, we apologists shouldn't think of our role more highly than is warranted. It is important for somebody to do it, since there really is good evidence for Christianity, and that terrain definitely shouldn't be ceded to the enemy without good cause! But it isn't usually where the main battle is, at least not for most potential converts.

In any case, I continue to maintain that it is unreasonable for a person convinced of Theism for other reasons, to lose sleep or become "disturbed" just because they were expecting a single argument to do more than a single argument CAN do. The fine-tuning argument has several strengths when playing to a scientific-minded crowd (e.g. it is based on modern physics, and there are relatively objective ways of evaluating antecedent probability) but it also has certain weaknesses, and it shouldn't provoke a crisis of faith to notice them.