I. Introductory Remarks

From time to time people email me with questions about Christian theology, or about how various aspects of modern physics relate to God. Although I am extremely busy these days, I do sometimes try to answer such questions, especially when it is clear that the topic is related to a spiritual struggle that the questioner is going through.

(If I have not answered your email I am sorry about that. Between caring for small children, an academic career, and some health annoyances, I've had less time to answer everybody who writes to me. When I do answer people, it is often after a delay of weeks or months. Thanks for your understanding, and please don't assume that because I don't reply, that I therefore didn't read your email or pray for you.)

If your question is more philosophical and less personal, it might be better to post it to the comment sections of this blog rather than to my email. For one thing, this gives other people the chance to post their own answers, and also to benefit from any replies. We can all learn together!

However, sometimes a person's question is deeply personal, and in this case it is natural not to want your question to be exposed to the public. In such cases, writing to me by email might be more appropriate. However, it is still somewhat inefficient if I see the same issues over and over again...

Because of this, I've decided to collate some things I've written to some people struggling with one very specific spiritual problem, which can cause great suffering to the person afflicted. If you don't have this particular problem, then great! This blog post is not for you. But I am sure there must be thousands of people out there who need to read this post.

Disclaimers

This blog post is not about me, specifically. For some reason it is hard to write a blog post about mental health problems without people assuming it is some sort of cry for help, or a round about way of confessing something that I have been struggling with recently.

It's true that I wouldn't have been able to help people struggling with this problem, if I were not also a fellow human being, who has suffered from my own doubts and emotional anxieties and struggles (Hebrews 5:1-3), which bear some similarity to the problem the other person is having. But the descriptions in this post are based at least as much on seeing this pattern in the lives of others, even if some of the advice is based on things that have helped me in the past.

If you are one of the people who has written to me about your spiritual struggles, please be assured of the following:

(a) Nothing in this post can be used to identify you; your confidentiality is always assured unless you explicitly tell me otherwise.

(b) Although I might quote my own words from emails that I wrote to you, this post is not about you as a specific individual, but rather about a common pattern that affects many people. That is, of the  people who have written to me about this issue, even if we leave you out of it entirely, I could still have written this blog post based entirely on the other

people who have written to me about this issue, even if we leave you out of it entirely, I could still have written this blog post based entirely on the other  people.

people.

This blog post is written for people suffering from a particular sort of spiritual anxiety. If in the last 2-3 months, you have spent less than 1 hour / week worrying about whether your religious beliefs are true, then this blog post is probably not for you. Or, if you spend more than 1 hour per week thinking about this topic, but both of the following are true:

(A) you usually don't experience significant negative emotions while doing so, and

(B) you are usually able to set these thoughts aside, in order to engage in other important activities (such as work, hobbies, interacting with family/friends, or sleeping),

then again this blog post is probably not for you!

(Indeed, if you hardly think about the question of religious truth at all, then you might be better served by a stern warning about the importance of the subject! If there might be a God who loves you and wants you to be eternally happy, but who also expects you to live in a certain way, shouldn't you want to know if this is the case? But, I assume the people who need to hear this sermon probably don't overlap very much with the Undivided Looking readership.)

II. What it looks like

The pattern I want to discuss is the case of a person who becomes obsessed with Christian apologetics (i.e. the defense of Christian beliefs) to an extent that becomes emotionally unhealthy.

Something triggers them that is either an event (e.g. the death of a friend), or an argument (e.g. reading an atheist cosmologist who thinks God obviously doesn't exist because the universe [did/did not] have a beginning); or perhaps they are reading the Bible and see something which seems to them to be a contradiction; or perhaps they have a meloncholy or anxious temperament, that is inclined to dwell on doubts about God's existence or goodness.

Usually the person with this pattern of doubts is a devout religious believer, but in some cases they might also be an irrelegious person who doesn't like Christianity, but can't seem to get out of their mind the idea that the judgemental God they perceive in the Bible might somehow still exist, and so they seek a dialogue with a religious believer to voice their fears and anxieties.

For concreteness, let's invent a concrete fictional questioner named George, and I am going to suppose that he is a devout but struggling Christian. (By this blog's eccentric canonization policy, I suppose I ought to therefore call this fictional character Saint George. This is fitting since he does have a dragon to fight.)

Let's suppose that St. George was raised in a church with a somewhat insular and fundamentalist worldview. He was led to believe that Darwinian Evolution is just atheist propaganda, invented by people in order to attack the biblical account of creation. For a while in high school, he was fed some young earth creationist material which led him to believe that there was some actual scientific evidence that the world is actually only a few thousand years old. But after he went off to college, he realized that it is difficult for a scientifically literate person to believe in this.

This leads St. George to a crisis of authority. The people who taught him made some really bad arguments for Christianity. But maybe there are also some good arguments?

In his spare time George tries to assuage his fears by reading Christian apologetics (or watching videos), as much as he can find online. He discovers that there are some intelligent seeming Christians out there, with a worldview more open to scientific knowledge, who nevertheless believe that there is good evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus. Or, he might get interested in various arguments for the divine creation of the universe, for example Cosmological Arguments (based on contingency or based on Big Bang theory or whatever).

But in order to be fair, and to seek out challenges to his worldview—and perhaps also because of the fascinating attraction of opposites—he also consumes anti-religious works on the other side, in order to compare the quality of the arguments. So far, so good. But while St. George finds some of the answers given by the Christians seem to be persuasive, others may not seem so convincing.

Or the answers raise a whole new crop of issues and objections. OK, we know that the disciples didn't steal Jesus body because there were guards at the tomb, but how do we know that St. Matthew didn't just invent the story about the guards, or that the Gospel was written by somebody else entirely? And here's an atheist on the internet who claims that some random paper on the arXiv shows that the universe might not have had a beginning.

Nothing ever seems to be fully definitive. (How can it be, when it seems that the justification of Christian faith depends on so many different historical and philosophical factors, which people have been arguing about for centuries?)

George starts to wonder if the problem is with himself or whether the problem is with what he was taught. How can he resolve these perplexing doubts and difficulties? Does he really need to be an expert in quantum cosmology and biblical criticism in order to decide whether God exists?

Does he simply need to find the right experts, and trust them to give him all the answers? But what if the experts disagree, or if he picks an expert based on the fact that they are telling him what he wants to hear? It was a shock when he first learned that there are bible scholars with PhD's from top universities, who think that what he believes about the Bible is dead wrong.

Patterns of Addiction

To assuage these worries, St. George increases his consumption of the product. After all, some of the articles he read by Christian apologists did seem to be helpful for resolving many of the sillier atheist objections. So it seems like if he can only ask enough questions, and watch enough smart people debating the issue, maybe he'll reach a state of realization or enlightenment where his intellectual (and spiritual) problems will be resolved.

Unfortunately, this is a potential pathway to addiction. Apologetics is obviously not chemically addictive, but anything can be psychologically addictive if the right conditions are met. That is, St. George is in a situation where doing activity X causes him to feel bad, but where his beliefs are such that it seems the right way to respond to these bad feelings is to do X again. This can cause a feedback loop where X grows and takes up more and more of his thoughtspace.

Now let me be clear. I don't mean to imply that being interested in Christian apologetics, or deeply caring about its outcome, is in and of itself psychologically unhealthy, and that researching apologetics is necessarily a wrong thing to do when faced with religious doubts. Obviously not, or I wouldn't have written a bunch of apologetics posts!

It's perfectly reasonable to want to do some research to find out whether what you believe rests on a secure foundation. For the vast majority of people, that's all it ever is and this blog post is not about you. Please keep doing what you were doing before, and if you were happy before, please don't become unhappy by wondering if you have some sort of apologetics neurosis. (Just because you might say, in a causal conversation to a friend, that you are "obsessed" with some hobby or interest, doesn't necessarily mean you are obsessed in a clinical, bad sense of the word.)

If you really do have the bad sort of obsession with religious doubts, you'll know it because it was already making you miserable—I mean before you started reading this post, and wondering about whether it describes you. This is not a problem you can have without knowing about it!

As in other cases of addiction, the instinctive response to dealing with the difficulties caused by excess consumption can sometimes be to double down on the tactics that were originally used to try to solve the problem, by "increasing the dosage", so to speak. So St. George spends more and more time on the topic. This of course also increases his chances of thinking about the subject whenever he is not reading about it. In fact, he starts to experience his doubts in the form of intrusive thoughts, which make it very difficult to concentrate on his work, or his studies in school.

Pretty soon the other areas of his life start to suffer. To quote a psychological criterion for when a mental pattern becomes a disorder), St. George has started to experience "significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning".

[I have omitted the word "clinical" here since this I am not a professional psychologist and this blog post is obviously not formal medical advice.]

If St. George has a tendency towards OCD or an anxiety disorder or depression—again, these conditions are nothing to be ashamed of, and these personality traits can exist in mild forms as well as severe forms—then these may be complicating factors. It might even be that St. George would benefit from seeing some sort of therapist (although if so, he should try to find one who is able to respect the ways in which religion can play a positive role in his life). Human beings have both bodies and souls, and each one affects the other in a complicated way.

It is important to emphasize that none of this means that George is crazy, or about to go off the deep end.

In fact, St. George is quite possibly a highly rational person, whose beliefs might in several respects be more accurate than those of other people. Nevertheless, he has a mental health problem—and this is nothing to be ashamed of, it happens to literally everybody on the planet from time to time!

However, St. George has a problem he doesn't seem to be able to reason his way out of, in part because St. George has a false belief about what his problem actually is, and therefore what is the right way to fix it.

What people want me to say

St. George might stumble across my blog or webpages and say to himself, "Gee, here's a Christian with a PhD in physics, who is an expert in quantum gravity. I'll write him an email and he can sort me out!

Dear Dr. Wall,

Sorry to bother you since you must be busy, but as a fellow believer in Christ I'm hoping you can help me with a problem. I've been struggling with anxiety about my faith ever since I heard about so-and-so's cosmological model where the universe comes out of a Giant Trombone instead of having a beginning. Is the Giant Trombone theory really true? Please help me!

Best wishes,

George

Now it usually is true that the Giant Trombone theory (or whatever is the flavor of the month) is a highly speculative idea with little evidential support, and I will probably be able to say some things that will reassure St. George about that particular point.

At the same time, I can't help but feel that St. George is putting me in a somewhat false position, i.e. that he expects a certain degree of scientific certainty which I can't and shouldn't provide. What St. George really wants me to say is something like this:

Dear George,

There is no evidence whatsoever for Giant Trombone theory. In fact, speaking from my authorative position as a scientist, the data is completely conclusive that the universe had an absolute beginning of time. Only a person who is totally biased, with an a priori prejudice in favor of atheism, could believe otherwise. For this reason, you can be quite certain that the universe was created by God 13.8 billion years ago. I hope this resolves your spiritual difficulty.

Blessings,

Aron

But I will never, ever write this email, because it would compromise my integrity as a scientist and as a theologian to do so. As a scientist, I need to allow for the possibility that Giant Trombone theory (or whatever it is) might turn out to fit the facts, or that there is some aspect of it which I can learn something from.

And speaking as a theologian, I know that God is allowed to create the universe in whatever way he pleases (either with or without a Giant Trombone) and that the Big Bang theory can't really be the primary foundation of the Christian faith—for the very obvious reason that Chrisitianity is about 20 times older than the Big Bang model (as first proposed by the Catholic priest St. Georges Lemaître), so it can hardly be the reason why anyone before him believed in God.

For me to endorse, even implicitly, the misconception that the existence of God is primarily supported by the Big Bang model, would commit me to thinking that every Christian in history from St. Peter to the time of St. Maxwell believed in Jesus for the wrong reasons.

Admittedly, if the Giant Trombone theory were actually confirmed to be true (which is admittedly kind of unlikely, because I just invented out of whole cloth a few paragraphs ago), it might be a little bit relevant to some questions. It could potentially push the scales of evidence a little bit, one way or the other, on certain very specific technical arguments for the existence of God. On the other hand, it won't make any difference at all to several other classes of arguments, such as those which argue that even Giant Trombones would be contingent realities, and would stand in need of an explanation.

In other words it would contribute somewhat to the Great Philosophical Conversation about Everything. But it is a very serious mistake to think that God's existence rests on whether one very specialized type of argument for his existence is valid or not.

(I think it is probably true that a sufficiently powerful intelligence (e.g. an angel) could point out flaws in any arguments a human being might make for the existence of God, or indeed for the existence of almost anything else that we think is real. But that does not mean the angel couldn't add: "Yet there is also something essentially right about your argument, if you were able to see even deeper into this topic as I can.")

If St. George thinks that reviving his certainty about Christianity requires becoming an expert in quantum cosmology, then St. George is simply wrong about how the Christian faith works. And it is more important to correct this wrongness, than to explain to him the particular ways in which Giant Trombone theory is unlikely to be true.

Long before Big Bang cosmology was a thing, someone wrote these words:

By faith we understand that the universe was formed at God's command, so that what is seen was not made out of what was visible. (Heb 11:3)

Let me be quite clear here that this word "faith" in the New Testament does not mean belief without evidence (as many atheists falsely allege, because that makes them feel justified in rejecting it.) The central meaning of the word is much closer to the English word trust. That is, it is primarily a word about relationships, not a word about propositions. Obviously, there are situations in which trust is justified—it all depends on who you are trusting, and what reason you have for trusting them!

If you trust a friend, then you will indeed believe certain propositions. Presumably you will have a good opinion about their character and reliability. Also, if you trust your friend's honesty, and expertise about a given subject, then you will also be disposed to believe whatever they tell you about this subject.

All of this is pretty obvious in a non-religious context, in which case a lot of questions about "faith" just sort themselves out naturally. Common sense says that faith is sometimes justified, and sometimes leads us astray, depending on who or what you put your faith in.

Faith only becomes a religious matter when the friend you are trusting is God himself, the Creator of the Universe. Because we can come to know, at least a little bit, the Creator, we can trust that he is the source of all the beauty we can see in the Universe. This sort of faith actually works in the opposite direction from apologetics about creation. The Christian faith starts with having a relationship with God (which is potentially available to everyone through his promises), and proceeds from there to become confident in God's ultimate control over everything.

This sort of faith was available even to people who lived before the Big Bang theory, or the disovery of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

Why doubts can't always be resolved in the way you want them to be

In some ways the root cause of the problem is, paradoxically, that St. George is conceptualizing his doubting as an intellectual "problem" which needs to be "solved", rather than a present emotional difficulty, which he needs to find resources to cope with. But life, including spiritual life, is not really a problem to be solved, rather it is something to be lived.

There are indeed intellectual puzzles which pop up along the way. These puzzles are important to think about, and banging our head against them helps us to learn what reality is like.

It is indeed true that that the deepest Reality is not an impersonal uncaring force, but rather a loving God. And that the best way to relate to these mysteries and puzzles ideally ought to bring you closer to God, rather than farther away.

At the same time, answering intellectual puzzles cannot be confused with life itself. A crossword puzzle can be solved, and then you are done with it. But a pet dog is not something which can be "solved" once and for all, and then it won't bother you anymore. It is a living reality which can be related to but not in a way which disposes of it. You can indeed "fix" a dog, but this only deals with one highly specific way in which the dog might be a nuisance to you.

If even a dog cannot really be related to properly with a problem-solution mentality, then still less is it possible for us to relate to God in that way.

St. George is probably a highly intellectual person, and when he encounters a new problem in his life, his instinct is to try to cast it as an intellectual problem to be solved. This means he has to recast the problem as a "debate" for which the proper solution is evaluating arguments. But if the original trigger for his spiritual difficulties was more of an emotional or relational difficulty, then this might be an entirely inadequate response to the original trigger for his doubts.

In fact, it may never be possible for St. George to resolve his problem using his chosen method, because it doesn't address the underlying emotional issue. In such cases, increasing the dosage of his chosen "medication" won't help, it will just increase the severity of the side-effects.

As St. Dorothy Sayers writes in The Mind of the Maker:

What is obvious here is the firmly implanted notion that all human situations are "problems" like detective problems, capable of a single, necessary, and categorical solution, which must be wholly right, while all others are wholly wrong. But this they cannot be, since human situations are subject to the law of human nature, whose evil is at all times rooted in its good, and whose good can only redeem, but not abolish, its evil. The good that emerges from a conflict of values cannot arise from the total condemnation or destruction of one set of values, but only from the building of a new value, sustained, like an arch, by the tension of the original two. We do not, that is, merely examine the data to disentangle something that was in them already: we use them to construct something that was not there before: neither circumcision or uncircumcision, but a new creature.

In some medieval versions of the legend, St. George finally defeats the dragon, not by killing it as you would expect, but by baptizing it. Immediately the dragon becomes completely tame, and he is able to lead it into to the village, where it begins to serve the people there.

Perhaps our modern St. George can take the lesson from this, that sometimes a "problem" is best resolved if we jump out of the initial framework we were trying to use to "solve" it.

A Change of Frame

You will notice that I have sometimes been discussing the issue of obsessing over doubts as if it were a psychological problem—a problem of addiction—rather than directly engaging with the contents of the doubts.

By this I mean no disrespect to the important philosophical issues that St. George's questions relate to. As a writer named Sarah Constantin says in a very insightful post called Sane Thinking about Mental Problems:

There are multiple ways of looking at problems with the mind. I don’t think that there’s a best one, but that it’s practical to switch between them pragmatically and to be mindful of the local advantages and disadvantages of each frame.

There is a medical model which "speaks of mental illness as a type of disease, which can be treated medically. The mentally ill are sick, and they can get well. They are patients."

There is a social model which treats mental problems as disabilities, which require accommodations by society in order to treat everyone fairly.

There is a skill based model which says that "problems of the mind are fundamentally about being weak at a skill, and recovery is about gaining that skill." About this approach Constantin says:

The advantage of the skill-based approach is that it incorporates the human capacities of learning and trying. Once you have the lightbulb moment of “wow, I can try to get better on purpose?”, once you start working directly on things rather than waiting for someone to “treat” you, your progress can accelerate quite suddenly. The skill model takes you, meaning your “wise mind” or the part of you that wants to be sane, seriously as an agent, and enlists your effort and intelligence.

But I was most interested in how she described a spiritual approach to mental illness:

What I’d call the “spiritual model” is a final family of viewpoints, which are related in that they take the denotational content of mental problems seriously, especially mood problems.

In this model, if you are having a crisis of faith, then your depression is fundamentally about religion, and you’re going to need to figure out your answers to religious questions. If your problems take the form of extreme guilt, then you’re going to have to engage with ethical philosophy and figure out a form of ethics that is compatible with life. If you’re experiencing nihilistic despair, then you’re going to have to find a source of meaning. If you’re having delusions, you might need to build up a stable epistemology.

The spiritual model takes unhappiness as a normal or even universal part of the human condition, not something exclusive to “abnormal psychology.” People get profoundly unhappy; people have to find a way to overcome despair; the way to overcome your despair is to figure out where you have a misunderstanding and gain the insight that will resolve it.

The advantage of this approach is that it is much more individual and fine-grained than the other approaches. It deals with your mind, not the generic mind that has similar problems to yours. And it engages with your mind, including your mental illness, as a peer — not as something to fix or to accept, but as someone to talk to and listen to. It allows for the possibility that your strange thoughts while depressed or manic or whatever might in fact be true, at least in some facets. There’s a sense in which resolving inner conflicts is “getting to the root of the problem”, actually untangling the knots in your mind, rather than “merely” palliating symptoms. The work of life, from the spiritual point of view, is building a valid and life-sustaining personal philosophy, and almost incidentally, this will resolve many “psychological problems.”

Although I have no particular reason to think that this blogger is a Christian, I loved the way she described the spiritual approach here as taking people's search for truth and meaning seriously—to ask what really does give our lives meaning. Our hearts demand that this be a legitimate question to ask.

I would add that if it turns out that God is the Deepest Truth, and if our relationship to God defines our truest identity, then it would be a mistake to try to construct a purely secular notion of "mental health" in which the answers to religious questions play a marginal role. If God is our true Father who loves us, then anyone who is living as an atheist is for that very reason mentally ill, out of orientation, living out a delusion. Even if they don't go around dancing naked in the streets, or screaming that people are out to get them.

However, this spiritual frame also has its potential pitfalls:

The downside of this approach is that sometimes your problems aren’t really about anything discernible, and it’s counterproductive to try to seek meaning in them, rather than just trying to manage or treat or accommodate them. Sometimes trying a spiritual approach just means getting trapped in ruminating or becoming an “insight junkie”, with no productive effect on your actual problems.

It’s very rare to see discussions of mental illness that treat multiple possible frames as valid and usable. I’ve seen personal narratives where people shifted from one frame to another and present it as “seeing the light,” but I think that’s not the whole story. I suspect that successfully living with, or recovering from, mental problems involves being somewhat eclectic about frames.

To summarize: when one frame doesn't work, it's worth trying out a different frame. St. George is trying to treat his problem of obsessive doubts as a spiritual problem. And to the extent that the doubts raise genuine philosophical issues which need to be resolved, that is legitimate.

But supposes he finds that, even after "resolving" the issue as well as he reasonably can intellectually, that his mind just goes right back to Step #1 and begins the process all over again, so that he is caught in an infinite loop. And that this looping process is partially involuntary, and occurs even when he wishes it wouldn't.

In that case, he might do better to think of his doubting as an illness which he needs to recover from. Or perhaps, as a condition for which he needs to develop skills to prevent these doubts from hijacking the rest of his life.

Not to mention, preventing these doubts from derailing his spiritual walk with God. (Despite the way they dominate St. George's self-consciousness, in all likelihood these doubts are in some ways peripheral to George's actual walk with God.)

No One is Alone

A lot of people might however be reluctant to take the step of trying on the "illness" frame because of the way in which our society stigmatizes mental illness. But the truth is that almost every human being suffers from some kind of mental problem or another, and there is no sharp line separating the "well" from the "ill".

Mental health problems are not the same as sins. According to orthodox Chalcedonian theology, this means that as a human individual, even Jesus was able to suffer from difficulties and burdens of the mind, such as depression. The prophet Isaiah portrays the Suffering Servant (whom Christians identify with the Messiah) as suffering from depression regarding the apparent lack of success of his ministry:

But I said, "I have labored in vain; I have spent my strength for nothing at all. Yet what is due me is in the LORD's hand, and my reward is with my God." (Isaiah 49:4)

and we know from Christ's words on the cross, that even the Son of God was able to feel abandoned, in a world where his Father seemed to be totally absent (even though in reality the Father is never absent).

And this is why the following verse about the Savior is true:

Can we find a friend so faithful

Who will all our sorrows share?

Jesus knows our every weakness,

Take it to the Lord in prayer.

So the fact that St. George has a mental burden which he finds difficult to bear, does not yet distinguish him from Jesus.

George might choose to reframe his doubts as a form of suffering, treating an episode of spiritual anxiety just as if it were a bout of nausea. What then? In that case he would try to avoid things that trigger such episodes whenever possible, and would ask God to “let this cup pass from me” to the extent possible. But when it must be suffered, to just try to get through to the other side somehow or another, knowing that he will eventually get through it.

Even Jesus was tempted to try to prove that he was really the Son of God, by taking an illicit shortcut by "testing God". Jesus declined this offer. (And if you want to follow him, so must you.)

However, unlike Jesus, St. George is a sinner, and this means that he will probably be doubting God in ways that Jesus wouldn't, and he won't be bearing his burden with the same degree of patience and trust that the Son of God would. Nevertheless, he will become more Chrsitlike to the extent that he prayerfully refers all his difficulties (most especially including St. George's present suffering due to doubts) to the loving care of the Father.

Afterlife Anxieties

[While the whole point of this section is to be reassuring, feel free to skip to the next bold section if you prefer not to think about this topic right now.]

A complicating factor in some cases is the fear of damnation (either for themselves, or for friends and family members), either as an explicit fear, or an implicit motivating factor.

Suppose that St. George has been raised in a church which teaches that God automatically sends everyone who dies without believing in Jesus to Hell. (His church's teaching might actually be more nuanced than this, but the question is which theological impressions are controlling George's mind, which may not even be the same as the theology that he would consciously state if you ask him what you believe.)

This fear of Hell thus acts as a disincentive for a religious person to accept any possibility of a non-religious perspective being valid. Yet many intelligent Christians are sufficiently self-aware to notice this effect on their own minds, and worry that it is compromising their judgement.

Also, the doctrine raises its own set of thorny (and emotionally disturbing) questions about the justice and goodness of God (even though God is both our Father and the Supreme Good), so now St. George has yet another set of religious doubts and fears to process at the same time.

Actually, this effect can work in both directions. A person who might be in the process of journeying from unbelief to Christianity, can find it difficult to admit it to themselves—because taking the possibility of Christianity seriously, could also require taking eternal punishment seriously as a possible outcome. Conversely, many people raised as Christians deconvert, precisely because they experience the threat of Hell primarily as a form of intellectual blackmail, and the only way to win that game is to take a hard line, by refusing to play.

If only they knew how much God loves everyone, and how much he desires for everyone to be reconciled with him! That God has no desire to punish for the sake of mere revenge, but would much rather bless us with the richest of rewards. And that none of the warnings in the Bible were intended to stunt anyone's intellectual or spiritual development—not at all—but only to prevent people from selling their birthright, by refusing to grow and to love by means of various evasions.

One day Christ will return and he will rebuke those who, like Job's friends, tried to use "orthodoxy" (as they undersood it) not in a redemptive way, but as a tool for controlling people, in order to try to keep people from asking honest questions or thinking for themselves.

Anyway, when this doctrine of eternal punishment is introduced in a clumsy and controlling fashion (which is a million miles away from the actual point of the doctrine) it tends to cause both religious and irreligious people to try to repress any spiritual doubts they might have. Because if they took their doubts seriously then it would make them extremely uncomfortable.

But if you belong to the minority of people, who aren't able to repress these doubts, but also don't yet know how to process them in a healthy manner, then you are one of the people I'm writing this post for.

Suppose St. George thinks he might lose his faith by reading a sufficiently convincing atheist argument. Now his own eternal happiness also seems to be at stake. That bombastic, confident, suave infidel on the Internet has become an existential threat. But on the other side, St. George thinks that, as a Christian and as an honest man, he also has an obligation to seek the truth. And this means that he should try to believe whatever is best supported by the evidence. This can lead to a sense of conflict within the saint, between the twin demands of fidelity and honesty.

The conflict really arises because St. George has a false picture of God the Father, since he believes on the one hand that God is just, but also that it is possible that God would punish him for exercising a virtue (namely honesty). This is a contradiction in St. George's worldview, that he will need to find a way to resolve.

(In fact St. George is probably exaggerating the likelihood of his falling away from the Christian faith. His fear of apostasy arises from the same place as his other neurotic fears, by imagining a "worst case scenario" and then playing it out in his head. But in what follows I don't want to dismiss this concern, but rather to face it head-on.)

Some Christian denominations teach that it is not possible for Christians to lose their salvation. But this makes less of a difference to than you might think, since religious people inclined to neuroticism can always find a way to make their religion support their neurosis, no matter what their explicit religious doctrines are. St. George will simply transfer his doubts and fears to the question of whether he was ever saved in the first place. Maybe he never invited Jesus into his heart properly; since if he did, then why is he suffering from these current perplexities?

(This problem can be exacerbated in a church environment that encourages Christians to always give an up-beat testimony about how their spiritual walk is going. There is a sort of "emotional prosperity gospel" in some evangelical circles, an expectation that if you aren't happy enough then you don't have enough faith. This is almost as destructive of a heresy as the physical prospertity gospel which teaches that faith in God leads to material riches. If you are attending a church like this, you should consider finding another place that allows you to express your real feelings.)

It's sort of a Protestantish version of a Roman Catholic with scruples, who might think that he has to go over and over again to Confession, in order to confess the same sins, because he fears that he might not have done it properly and with full sincereity the first ten times.

Except that, because Protestantism teaches that salvation is by faith and not by works, a Protestant's scruples are more likely to concern the question of whether he has enough "faith" to be saved. (If he is a Calvinist he would instead worry about whether he is predestined to be among the "elect".) As though faith were a psychological state that has to be drummed up with willpower, rather than the gift of God which is granted to everyone who turns to Jesus. (Ah, says the scrupulous person, but it has to be a sincere turning to Jesus, and how can I ever know that I was really sincere in doing so?)

Actually, the main point of the Protestant Reformation was to prevent people from relating to God in this pathological, neurotic way. But that doesn't stop individual Protestants from missing the point and doing it anyway. Rather than saying, along with St. Paul,

"If God is for us, who can be against us? He who did not spare his own Son, but gave him up for us all—how will he not also, along with him, graciously give us all things? Who will bring any charge against those whom God has chosen? It is God who justifies. Who then is the one who condemns? No one."

(Romans 8:31-34)

St. George is acting (however much he may try to obscure this to himself) as though his faith is primarily based on some mental contorsion which he needs to accomplish in himself. Rather than being a work which only the God can do, and which God will do if he waits patiently.

These fears and anxieties can exist side-by-side with a real and genuine love for God, and a desire to enjoy him in a less self-centered way. But in St. George's case this love has not yet fruitioned into the mature state spoken of by St. John, who writes that:

There is no fear in love. But perfect [i.e. complete] love drives out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. The one who fears is not made perfect in love. (1 John 4:18)

When St. George reads a passsage like this, his instinctive response may be to feel guilty because he doesn't measure up to this standard. He may think that the doubts are his own fault, and that he wouldn't be having this problem if he were only capable of the kind of trust in Jesus that other Christians seem to have.

But even if all that were true, it doesn't follow that feeling guilty about it is going to get St. George any closer to perfect love, or that guilt is a useful feeling to have about this. Yes, God wants to give you this experience of trusting love, but not everyone can expect for it to be be perfectly formed from the beginning of their spiritual walk. Often it only comes with time and maturity, so there is a need to be patient with yourself.

Maybe it would be better for St. George to try feeling compassion for himself. The New Testament says:

Be merciful to those who doubt. (Jude 22)

St. George would probably be more charitable towards another person who told him about similar spiritual struggles. St. George needs to realize that if he would have compassion on another person experiencing the same struggles, then God must feel even more compassion towards those having these struggles—including compassion for George himself.

And that is why George is more likely to resolve his anxieties by means of growth in love for his neighbor, than by any amount of religious reading. If George becomes the sort of person who loves his neighbor unconditionally, then he will also find it easier to understand how God can love him unconditionally.

Exiting the Loop

In order to make progress, St. George needs to make a conscious decision to exit the mental loop and to decide how he is going to live the next portion of his life—either as a Christian, as a seeker, or as a skeptic. And once he makes this decision, he needs to stick with it for the time being, and not simply go around and around and around in the mental-doubt ferris wheel.

(Let me be clear once more that I am talking to people who have been stressing about this issue for a long time, and are suffering as a result, and trying to give them permission to take that feeling of pain as a legitimate reason to do something different. If you are encountering Christianity and the arguments for it for the first time, or if you are currently enjoying learning more about the arguments on both sides, then this blog post is not for you. God might still be asking you to make a decision to give your life to him, in which case you should trust him with that. But you aren't suffering from the type of obsessive doubt that I am describing here, and depending on your personality and a gazillion other factors, maybe you never will.)

If you are in St. George's position, it might help to ask yourself what you would do if you were actually forced to decide now. Suppose you needed to cross a scary bridge in the Amazon jungle to bring supplies to help missionaries translate the Bible, or you were trying to comfort a dying child asking you questions about Jesus and Heaven. Suppose there were a clear difference between the course of action you would take if you believed it was all true, and if you didn't. What would you attempt to do?

In fact, since there are always ways to obey Jesus's commands more faithfully in any life circumstance, this isn't really a hypothetical question. You are always in a position to make a decision and act! The verse:

Trust and obey, for there's no other way

To be happy in Jesus, but to trust and obey.

isn't just for children, but for adults also. If your intellectual ruminations aren't oriented towards active trust in what you believe—towards some actual actions—then it should be no surprise if your mental processes have gone of the tracks. Trying to force yourself to to "trust" in some way that is decoupled from obedience is total nonsense. Trusting Jesus doesn't mean managing to execute some complicated mental gymnastics in your head. It means doing what he said.

(I mean, to the extent that you understand what he wants you to do. I'm not advising you to initiate a new series of doubts about some part of his teaching that you don't understand yet, say about whether he really wants you to sell all of your possessions and give them to the poor. But rather to pick one thing Jesus said, however small, and start doing it.)

Perhaps you could start by forgiving one enemy or buying clothes for one homeless person. The saints in the Bible who were praised for their faith, like Abraham or Rahab, always expressed that faith by some specific action. Otherwise how would we know about their faith?

As another St. George (MacDonald) wrote,

Obedience is not perfection, but trying. You count him a hard master, and will not stir. Do you suppose he ever gave a commandment knowing it was of no use for it could not be done? He tells us a thing knowing that we must do it, or be lost; that not his Father himself could save us but by getting us at length to do everything he commands, for not otherwise can we know life, can we learn the holy secret of divine being. He knows that you can try, and that in your trying and failing he will be able to help you, until at length you shall do the will of God even as he does it himself. He takes the will in the imperfect deed, and makes the deed at last perfect. Correctest notions without obedience are worthless. The doing of the will of God is the way to oneness with God, which alone is salvation.

Making a decision isn't going to magically make it so George never experiences the emotion of doubt again. Time and patience are required. But as long as his will is in the right place, he will get to the right place in the end.

If St. George wants to be happy while journeying towards that destination, then he needs to do whatever it takes to exit the infinite loop that is making him suffer mentally. Admittedly this cannot always be done immediately, by direct willpower alone. Hence, at least some of the time when he has spiritual anxieties, he needs to be willing to resolve these anxieties by engaging in spiritual practices, rather than by re-hashing the same intellectual arguments over and over again.

Spiritual Practices

Spiritual practices include things like: singing hymns, reciting the Lord's prayer, meditating on Bible verses, physical postures (like kneeling, bowing down, or standing) intended to express reverence, lighting candles or incense, etc, not to mention the great variety of different types of congregational worship services.

There are a great variety of such practices, used by different Christian groups. Rather than trying to catalogue them all, I will simply note that all Christian groups recommend such practices, and that (assuming theological soundness) you are free to pick whichever practices help you the most.

It should be noted that spiritual practices that reduce anxiety, often involve repetition, which is facilitated by the use of pre-existing material. (For example, at a moment of severe anxiety, you might recite the same Bible verse over again, until you calm down.) To avoid possible scruples, it is worth commenting on the compatibility of such practices, with Jesus' teaching that:

"When you pray, do not keep on babbling like pagans, for they think they will be heard because of their many words. Do not be like them, for your Father knows what you need before you ask him." (Matthew 6:7-8)

Jesus' target here is a superstitious approach to prayer, in which we think that God will somehow be more likely to be swayed if we approach him with the exact right formula, or that prayer is like magic, so that the more you pray the more "power" is generated.

But I do not think these words imply that it is forbidden to repeat yourself while praying, if the reason for the repetition is for your own sake (because you want your soul to dwell in the words more deeply), rather than for God's sake (as if he somehow didn't hear you the first time).

And sincerity is indeed important, but this has little to do with whether a given prayer is extemporaneous, or composed by one of the saints who went before us. What matters is whether you yourself want to say whatever words that are being said. Sometimes one discovers that words written by somebody else, say exactly the thing you wanted to say, but couldn't find the words for. In that case there is nothing insincere about making those words your own.

[Note: if you happen to suffer from OCD, I am not suggesting that you follow any "compulsions" that arise from this source. Even if these compulsions seem to be religious in nature, they are not true spiritual practices and tend to weaken the will, rather than strengthening it. In general, a real spiritual practice will be something you want to do, because it is helpful, rather than something you feel like you have to do. If you have difficulties distinguishing between real spiritual practices and imaginary obligations, please consult with an experienced spiritual director.]

Later in this series, I will suggest a specific set of practices which may be helpful for those suffering from doubt.

Cultivating Perceptiveness

What I am saying does not mean that George can never return to the intellectual arguments. The greatest questions of philosophy have the feature, that we never outgrow them. They keep getting richer, and more interesting as we learn more. So I don't mean to advise anyone to drop apologetics or philosophy of religion forever. But rather, to set them aside for a period, whenever they take the nature of an involuntary compulsion.

You can voluntarily chose to return to these topics at any time. If you take a long enough break, then you will be different the next time you come back to the topic, due to the new experiences and thoughts you have had in the meantime. As a result, when you come back to these deep questions, you will see new things, that you didn't see before.

Choosing to obey doesn't mean closing your eyes to the world around you. In fact there is nothing better than obedience to God, for shining abundant light, showing who people are, and what they need.

To perceive and to understand, is quite different from having obsessive doubts. Obsessive doubts, while they are sometimes caused originally by some traumatic situation, really come from internal causes. If anything, such obsessive doubts actually interfere with clarity of perception, and sound philosophical judgement.

So in addition to strengthening your will with voluntary action, feeling better may also require cultivating a greater connection to your sensory perceptions of the world around you.

(No, I don't mean going to Youtube and downloading yet another video about whether or not Jesus rose from the dead. Yes, technically that involves your ears and eyes, but the intellectual question and emotional anxiety is still in the driver's seat.)

Shut down your computer, and really look at the room you are sitting in. Is there any art? Are there any smells? Are you hungry, thirsty, or tired? Are there other people in the house, and if so what are they thinking and feeling? (It probably doesn't have much connection with your own religious doubts. That's a good thing! It's an opportunity to leave your struggles behind and think about something else.)

Are your surroundings boring? If so, it's no wonder you've gone down an Internet rabbit trail. What can you do to make your surroundings more interesting? And when was the last time you went outside?

You might object, "But how does this solve my intellectual problem with religion?". But God is everywhere, even in mundane reality, even when you aren't thinking of him. And life is not a problem to be solved. So do it, and you will feel better. And after you feel better, you will probably start thinking more clearly as well.

An Oversimplified Model of the "Soul"

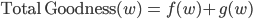

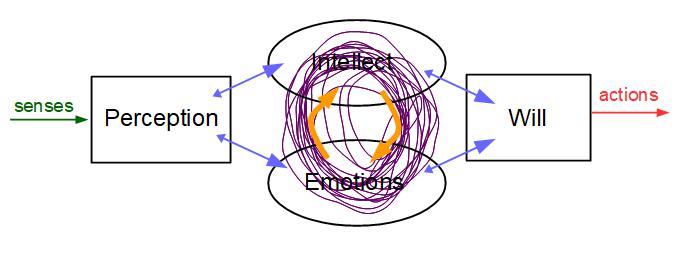

Just in case it helps, here is a pictoral model of what I've been saying in the previous section. In a cartoonishly oversimplified (i.e. mostly false, but hopefully still useful) picture of the "soul" or mind, you can imagine your mind as containing 4 different aspects or faculties: Perception, Emotion, Intellect, and Will.

They are all connected to each other as follows:

I've drawn arrows to show how "information" flows through us:

I've drawn arrows to show how "information" flows through us:

• In the first layer our external sense data informs our Perception—by which I do not mean passive receptivity, but rather our active interpretation and understanding of whatever we are currently experiencing in the world.

• Then Perception in turn influences Intellect (which constructs our theoretical model of the world, including "unseen" things we don't directly perceive, e.g. God or the back sides of objects) and Emotions (which generates feelings, either welcoming or aversive, to various things in our model).

• Additionally, each of the Intellect and Emotion strongly influences the other one internally. If you have a thought about the world, this is likely to lead to some feelings, and if you have feelings about a thing, this is likely to lead to further thoughts. (Indeed, without some emotion, our thoughts can't function, because you have to at least care enough about the subject matter to bother thinking about it!)

• Then Intellect and Emotion both in turn influence the Will, our decisionmaking capacity. This in turn leads to external actions in the world.

[One could dress this sort of thing up with neurology techno-babble, for example I could say "motor cortex" when I talk about taking actions, but I suspect that this sort of thing would lead people to take the models too seriously, so it's really better to keep things at the level of "folk psychology"!]

Note that the blue arrows actually go in both directions! The primary direction of influence that we more normally consider goes in the forward (right) direction, but the secondary direction (left), shown as smaller arrows, are also important. Our Intellect and Emotions affect what we perceive. And our Will affects our thinking and feeling, as well as which perceptions we choose to pay attention to. (There should also be some arrows directly between Perception and Will, but the diagram is complicated enough as it is!)

It is possible for mental functioning to flow in a smooth stream from left to right. When all 4 faculties are fully engaged, this will tend to look like one of 2 patterns:

Perception -> Intellect -> Emotion -> Will;

or:

Perception -> Emotion -> Intellect -> Will,

but with various forms of feedback operating in the backwards directions, to keep things on track, regarding whatever activity you happen to be engaged with.

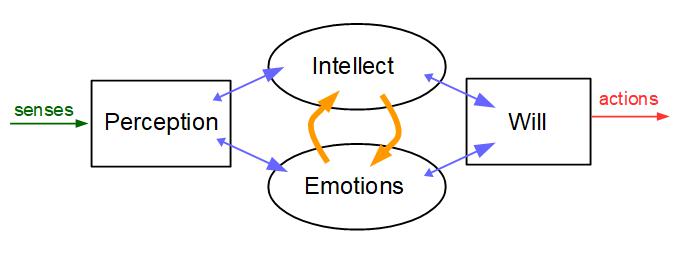

But what happens in the case of a person afflicted by severe doubts? In that case it looks more like this:

What's happening here is a sort of feedback loop between the 2 "internal" faculties (Intellect and Emotions), where because you feel strongly about a topic, you keep thinking about it, but this produces more feelings:

...Intellect -> Emotion -> Intellect -> Emotion -> Intellect -> Emotion...

Of course, there's nothing bad about these orange arrows per se, which serve an important function. The problem is when it leads to obsession and needless suffering.

The conflicted thoughts (shown here as the purple squiggles) go back and forth in a circle in a way that is completely disconnected from your experiences in the actual world. This in turn causes disengagement from Perception and Will, as the main crisis in your life is primarily about mental constructs in your own head, not your bodily experiences. [I am not of course saying that God and Jesus are mere constructs in your head, but your obsessive doubting about them is an internal mental activity.] But this disengagement in turn makes the doubting worse, because it removes from your life anything that might distract you from your cycling anxious thoughts.

It's sort of like how when you get a microphone too close to the speaker, it produces a loud SHREEEEEEE!!! sound. The good news is that this can be fixed through a repositioning of your mental faculties. The difficulty involves a feedback look between Intellect and Emotion. But this feedback loop is a conscious mental process, which means that can only exist to the extent that we choose to pay attention to it.

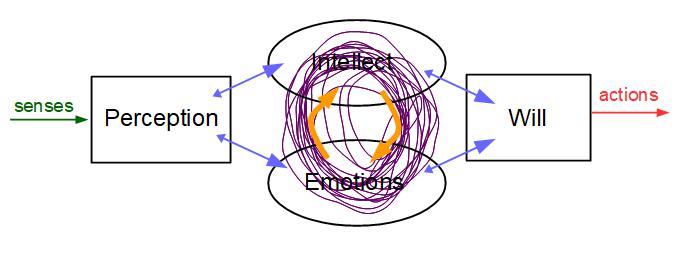

But you can't stop paying attention to something by simply willing yourself not to. Because this leads to the "Don't think about a pink elephant!" trap. (You just did, didn't you?) The solution is instead to deliberately choose to think about something else.

This requires strengthening the "external" mental faculties that aren't participants of the feedback loop (Perception and Will). Specifically, this means selecting activities that allow you live more fully in your Perception (paying attention to sensing the world around you). And also—either separately or at the same time—learning to focus more on your Will (paying more attention to making decisions, leading to concrete actions in the world).

This doesn't mean your Intellect and Emotions will be unengaged, but they will be differently engaged, in a supporting back-up role, to some activity where Perception or Will are taking the lead.

(Of course, my point is not that Intellect and Emotion are unimportant. Rather, the system has gotten out of balance, and we are trying to restore that balance! There are other people out there who are imbalanced in a different way, and who would need the opposite advice, but these aren't the people afflicted by obsessive religious doubts.)

III. Shouldering the Weight of the Sky

St. George might sometimes feel tempted to express his persistent doubts by saying something like, "I can't seem to get God out of my head!". This is a somewhat odd way to put the problem though.

The perpetual contemplation of God, even while going about one's work, is something a lot of religious people aspire to. Even missionaries, pastors, or monks and nuns often find it difficult to remember God in all things, and now here you are trying to forget him!

Unfortunately, St. George's neurotic loop is a very different phenomenon than mystical contemplation. St. George can't get over worrying about whether God really exists or not. Which is a very different thing from contemplating the mystery of the Trinity, or wondering at the humility of the Incarnation, or seeing Christ in the face of the person God has set in front of you to love.

Neurotic Obsession versus Prudent Care

St. George might try to justify his obsessive doubts by saying the following:

"The question of whether God exists is infinitely more important than anything else, and might affect my eternal destiny, therefore I have to put my life on hold until I find out what is true."

Now it is quite true that a lot of normal folks don't take enough trouble to try to seek out the real truth about God and the universe. Seeing that so many people give contradictory answers, many people without strong convictions assume the problem is insoluble, and give up in despair before they even start.

This despair may sometimes cloak itself in shallow relativism, but is often, I personally suspect, a stubborn will not to know the truth. For this reason, the chief job of the Christian apologist is not so much to convince people of facts, but to wake them up; to convince them to take personal responsibility for seeking the truth, so that perhaps they open their eyes and grope towards the light. (While keeping in mind that nobody can ever come to God without God's grace preparing the way beforehand.)

So it is quite commendable that St. George is searching for answers. But just because some people think about the issue too little, doesn't mean it is impossible to err in the opposite direction, by excessively overthinking it. As Aristotle pointed out, goodness is usually a middle path between the opposite vices of "too little" and "too much". For any given virtue (e.g. courage), you can either fall short of it (cowardice) or else overshoot the mark (recklessness).

But God is infinitely important. How is it possible to be too concerned about something which is infinitely important?

The answer is straightforward: if doing so does not in fact contribute to clarifying your thinking and affections about the issues at stake, but instead leads to a mental illness that places obstacles in your spiritual journey.

Nobody can ever love God too much, since God is utterly and supremely holy, and all good things proceed from him. Even all the praises of the most exalted angels, all the choirs of seraphim and cherubim, cannot fully describe or encapsulate his sublime glory and beauty. In this sense, there can be no such thing as an excessive amount of agape/charity towards God. Even an infinite number of angels singing his praise for an infinite amount of time could not fully understand everything which the Spirit knows about the Father and the Son. But nevertheless, this same Holy Spirit has been poured out on us, so that we can begin to know him, in his absolute uniqueness.

And yet a particular strategy for dedicating yourself to God can certainly be carried on to excess. As the Bible says, there is such a thing as "zeal without knowledge" (Proverbs 19:2, Romans 10:2). If your obsessions about theology are counterproductive, i.e. if they have the opposite effects from what you intended, and are the wrong method to reach your goal, then they can certainly be "excessive" in that sense, even if the goal is infinitely important.

Just because you need food to stay alive, does not mean that the optimal strategy for staying alive is to eat as much food as possible. You cannot have too much God the way you have too much food, but you can certainly have an excess of theological reading or obsessing about issues that don't make any difference to your practical obedience to Christ.

Feigning Certainty

This sort of self-sabatoging excess is more likely to happen if you have unrealistic goals about what can be attained from a given course of action. Although St. George thinks his doubts are due to his own limitations, part of the problem may be that his role models in the faith may be giving him unrealistic ideas about what real certainty looks like.

One possible mistake here is thinking that in order for your faith to be rationally justified, you have to find evidence which is so strong that it is enough to convince any rational person. (And therefore, anyone who knows about this evidence, whatever it is, and doesn't agree with the conclusion is irrationally resisting the truth.) But this is false.

Every human being has a different background, and is coming from a different place. There are all kinds of reasons why people, who seem reasonable in other ways, might accept or reject various arguments. In order for your faith to be rationally justified, you only need enough evidence to convince you that it is true, and this evidence might not always be something that you can easily communicate to others; especially if those other people have very restrictive rules for what types of evidence they consider to be valid.

Realizing that there are educated and intelligent people who disagree with you is part of the process of intellectual maturity. People with PhDs are a lot less intimidating to me then they used to be. In part because I've learned from experience just how astonishingly silly the claims of certain intellectuals with PhD's can be. One has to distinguish between the people who are telling you about some field of study that is based on solid evidence, and a person who merely wants to use their academic authority to promolgate their own nutty theories.

(In particular, I've learned to be quite skeptical of the theories of many biblical critics, who read between the lines of the Bible, and based on quite scanty evidence tell you the history of how it actually came to be written.)

It is true that you can find lots of people who reject Christianity, or Theism, for terrible reasons (or for reasons they can't even articulate). Some of these people are probably being dishonest with themselves. But that is between that person and God. Your faith cannot depend on judging the validity of other people's responses!

Sometimes an inability to tolerate disagreement even leads certain people to become amateur Christian apologists, since they have a psychological need to support their position by adopting a façade of total certainty. Unfortunately, this is not a good foundation for good reasoning.

One sees this a lot in religious (and political) discussions on the Internet, which have a tendency to degenerate into childish attempts to win arguments through pure bluster. "You're 99.99% certain God doesn't exist? Well as a result of the ______ argument, I'm 100% certain he does! In fact, everything I've ever read or seen only makes me more certain that a loving God exists!" "How can you say that, when in fact there is no evidence at all for the existence of an unfalsifiable invisible sky-fairy." The messages here on both sides are: Stand in awe of the degree to which I am completely persuaded by my own arguments! Everyone who disagrees with me must be a total moron!

The people in this conversation are like rookie poker players who, in every other hand, try to take the pot with an enormous and unjustified bluff (and then look totally surprised when this maneuver doesn't immediately convince everyone else at the table to back down).

That's why you can't allow yourself to be bullied by people who refuse to admit any rationality whatsoever in their political or spiritual opponents. Such people are really displaying their own intellectual insecurities, by constructing a false persona who is unable to be influenced by anything anybody on the "other side" says. Over time, the fakeness starts to contaminate their real self. Don't be like that.

(Humility does require that we be open to correction by others, but you have to be careful never to let somebody's fake self try to teach your real self.)

Problems with Debate

Even in classier settings, I'm not convinced that "debate" always has very much spiritual value. As soon as you start debating, the other person becomes your "opponent", and instead of trying to mutually seek the truth, it becomes a game or sporting event to be won or lost. Then each party becomes a "lawyer" looking for tricks to sway the audience, rather than laying their cards straight on the table.

In my experience, usually the only way to get through to a person who disagrees with you, is to have them stop thinking of it as an adverserial thing, where you are on one side and they are on the other side, because that makes them feel threatened by what you are saying. This is one reason why Socrates preferred conversation based on questions, rather than debate, for as he says to the rhetoritician Gorgias:

You, Gorgias, like myself, have had great experience of disputations, and you must have observed, I think, that they do not always terminate in mutual edification, or in the definition by either party of the subjects which they are discussing; but disagreements are apt to arise-somebody says that another has not spoken truly or clearly; and then they get into a passion and begin to quarrel, both parties conceiving that their opponents are arguing from personal feeling only and jealousy of themselves, not from any interest in the question at issue. And sometimes they will go on abusing one another until the company at last are quite vexed at themselves for ever listening to such fellows.

But if you are a Christian, you should know that true conversion never happens as a result of intellectual bullying, but rather by the work of God's Spirit in people's hearts.

So it seems a bit misguided to try to look for a champion Christian debater, to take on all the atheist intellectuals, like Dawkins and Krauss and Carroll and all the rest. It would be far better to pray for these atheists (as individual people I mean, not just as representatives of an opposing worldview). That's something you can do right now without needing to recruit a champion (besides Christ, who already shed his blood for them). If Christ is truly risen from the dead, then he doesn't need anyone to bend the truth on his behalf in order for him to be known!

The best apologists are also able to state the case for the other side, because they really believe in seeking the Truth, so they aren't secretly worried that one real truth will undermine another real truth. But the fake apologists for Christianity (and Atheism) can never summarize the other side fairly, because they are secretly afraid that if they ever did so it might convince somebody.

There are so many people today who are trying to get to spiritual results, by unspiritual means. They don't realize, the secret which St. Martin Luther King and Gandhi knew, that to do accomplish anything significant in this world, you first have to change yourself.

If you love the truth more than anything else, I think people around you will notice that, and you will be a witness to the light that shines in the darkness. On the other hand, if you take shortcuts and try to use dishonest methods to prove the truth, then the foundations will be rotten, and the structures you try to build on that will eventually tumble down.

The bad sort of apologetics effectively denies the ministry of the Holy Spirit, who illuminates and softens our hearts, and teaches us what is true. The Bible makes it clear that the divinity of Christ is obvious only to those who are given the spiritual eyes to see it.

The Work of the Spirit

As St. Paul said:

The person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God but considers them foolishness, and cannot understand them because they are discerned only through the Spirit. (1 Cor 2:14)

and

Therefore I want you to know that no one who is speaking by the Spirit of God says, "Jesus be cursed," and no one can say, "Jesus is Lord," except by the Holy Spirit. (1 Cor 12:3)

In my experience, the unhappy Christian with doubts (like St. George) is usually a person who does have the spiritual discernment to see Christ on the Cross as the supreme manifestation of the love of God—but has been distracted from this, by looking for certainty in the wrong places, where it is not always to be found.

Christian epistemology, because it is about God, is fundamentally Trinitarian in its structure. You need Jesus to come to the Father, but you can't see the Father in Jesus, unless the Spirit enables you to see it. God has graciously chosen to raise us, in Christ, into his own life. But if God has shared the mind of his own Spirit with us, this must necessarily mean (what else could it mean?) that there are some propositions which we do know, even if we can't explain how we know them. Only God can perceive God, but God has shared his life with us in such a way that we can participate in his self-perception.

However, St. George might well be confused about what the testimony of the Spirit is supposed to look like. Especially if he goes to a charismatic church where supernatural gifts like prophecy or speaking in tongues are regarded as the sine qua non of Christian experience. Or, if he goes to a non-charismatic church where the influence of the Holy Spirit is barely discussed. Either way, St. George might say to himself: "I don't know what all this talk about the Spirit is supposed to be about. I've never had any sort of voice in my head telling me what to do, or if I ever did, I was never sure wherther or not it was just my imagination." (Or in some cases, he might have gone along with a mental voice in his head for a while, and then decided maybe it wasn't God after all? That could certainly trigger an episode of doubt, if anything would.)

But it is not always true that if something is part of us, that we must therefore be conscious of how it works. Apart from an Argument from Authority (based on faith in those who study anatomy and medicine), I wouldn't even know that my kidneys exist. But they are vital to my functioning all the same. And if my kidneys started failling, I'd eventually start to experience the symptoms of illness, showing (in a negative way) that they were actually there there whole time.

If George is doubting the goodness or existence of God and Jesus, he's probably none too sure about the Spirit either. So I think it is worth reminding everyone that biblically, the test of whether you genuinely have the Holy Spirit is not blatant supernatural manifestations (most of which could be counterfeited anyway). The first real test is this: when you look at Jesus, do you perceive God? If so, that's what having the Holy Spirit feels like.

To give an analogy from the senses, it is impossible for an organism to see without having eyes and a brain and a visual cortex. In other words, you can't see any object outside of you without having something inside of you which is receptive to that sort of thing. But if you want to know whether your visual cortex is working, you can find that out most easily by looking at an external object which is outside of you and real. If you can see it, then you can reasonably conclude that your eyes and visual cortext are (at least partially) functional. Similarly, a test of whether you have the ability to perceive different pitches is to start singing. Or if you can reason about different quantities and shapes, then you have some mathematical ability. You don't learn about these abilities by introspection, but by doing them.

The Holy Spirit can indeed manifest through various supernatural gifts to specific people, but these gifts are neither a necessary or sufficient condition of holiness. So you don't need to bother about these other gifts too much, unless they happen to apply to you specifically (in which case there is no subsitute for getting advice from an experienced spiritual advisor who knows you personally).

The second test is similar to the first: are you beginning to love other people the way Jesus loves them? If so, that is another sign of the Spirit's presence. But of course this test is applicable only if you have been beginning to follow Jesus and obey his teaching. If not, why would you expect to know anything about it? A person who never tries to use their musical ability, can't be expected to have very much evidence of its existence.

Jesus' response to the question of why some people doubt, was to remind people that everything depends on obedience:

Anyone who wants to do the will of God will know whether my teaching is from God or is merely my own. (John 7:17)

Those who really want to do the will of God, will eventually learn whether Jesus' teaching is correct or not. But if you refuse to live in the Spirit, you shouldn't be surprised if your perception of religious truth is also dulled. Jesus also said:

Pay attention, therefore, to how you listen. Whoever has will be given more, but whoever does not have, even what he thinks he has will be taken away from him.” (Luke 8:18)

In other words, if you live out whatever insights you have already received (however meager they may seem) you can expect more and more information from the same source. On the other hand, if you don't live out what you've been given, you cannot expect to even have a good grasp on the doctrines you think you know. Obedience—that is, being willing to be like the Son of God—is a necessary condition for discovering their essential truth.

This does not of course mean that there is an absence of objective evidence for Christianity; such evidence does indeed exist, largely in the places where one would expect it to be if the thing had really happened. There really is historical evidence that miracles sometimes occur. And the New Testament really is written in a way that suggests that the Apostles actually had encounters with Jesus after he rose from the dead, and not in the way that you would expect them to write it if they were making up a religion for power and profit.

What there is not, is a God who is willing, most of the time, to perform miracles on demand simply to prove his existence to skeptics. I agree that that god doesn't exist. If an entity like that did exist, it would be quite different from the sort of God that is implied by the notion of a tempted, rejected, crucified Messiah.

And as for the world being full of suffering: well (for those with the ears to hear it) this is actually exactly the way you would expect the world to be, if (as Christianity teaches) suffering really were God's chosen means for redeeming a fallen world. I think that those who, even in deep suffering, look to what Christ does with suffering, will see the answer to many of their difficulties there.

However, it is naïve to think that these evidences will be capable of convincing most of those who are outside the faith. Unless they are, at the same time, transformed into a different sort of person capable of seeing things in a new way.

Or in other words, the only way to really know God is through the Spirit's revelation of the Son. As the Eastern Orthodox Christian liturgy says:

"‘Let us love one another, that with one mind we may confess:

‘Father, Son, and Holy Spirit; the Trinity one in essence and undivided’."

Without love for one another, it is not possible to know who God is. The only way to know God is that God has shared God with us. The Trinity isn't just an esoteric doctrine, it is our only real way of coming to know God in his fullness. If we try to become acquainted with God in some other way—besides the way that he has provided—we won't come to know what God really is.

The Full Evidence

Someone might say: I thought you were a big believer in Bayesian epistemology? So how can you now put the Trinity at the center of your epistemology? Is this some sort of Fideism, or Reformed epistemology, or Presuppositionalism, where one somehow sneaks in the basics of Christianity as an axiomatic assumption?

Not at all. I do actually do identify as an evidentialist—I think people should only believe in things if they have some good reason to believe in them—but I don't advocate for arbitrarily excluding psychological or spiritual experiences from the class of things which can potentially count as "evidence".