[It's hard to believe it's been nearly 3 years since the last post in this series; maybe writing about a "long delay" jinxed me. Anyway I got pretty busy with academic stuff, but now I'm on sabbatical. Like the rest of this series, the core of this post was written about 7-8 years ago, but I kept feeling like I needed to tinker around with it. But it's past time to release it into the wild, so here it is.—AW]

10. What is the general moral character of the religious teaching?

This is relevant for two reasons. First, a good person is more honest, and therefore less likely to try to deliberately trick other people into believing something false (see my previous section on fraud.) People who make up religions are hardly likely to be paragons of moral virtue in other respects. As Jesus said:

Watch out for false prophets. They come to you in sheep’s clothing, but inwardly they are ferocious wolves. By their fruit you will recognize them. Do people pick grapes from thornbushes, or figs from thistles? Likewise, every good tree bears good fruit, but a bad tree bears bad fruit. (Matt. 7:15-17)

By "fruit" Jesus means, not simply conversions or quantity of pious devotions (which any fanatical cult can produce), but rather the moral character of those who claim to be prophets of a true religion, which serve as a test of their claims to be supernaturally inspired.

Second, if God is good and holy—which is a core article of faith for all Abrahamic religions, and also Platonism—then presumably any religion he reveals must also be good and holy. In fact, one might well expect it to be supernaturally good, since if the religion merely taught ordinary human ethics, we could just as easily come to it by natural reason alone. This does not, of course, imply that the people God reveals his laws to will be morally perfect (if they had no flaws, they wouldn't need instruction) but the teaching itself should be morally good.

I. Making Moral Judgements

In comparing different religions for their degree of moral goodness, I am presupposing that moral virtue is not merely a matter of conformity to the arbitrary social conventions that one is brought up with, but rather that an open-minded person can recognize and appreciate goodness, even when it is embedded in a culture very different from their own.

In other words, I am assuming in this blog post that we will not allow ourselves to be bogged down by "Meno's paradox". In a conversation with Socrates, Meno tried to argue that it was impossible for a person who didn't already know what virtue is, to ever find out about it:

How will you search for it, Socrates, when you have no idea what it is? What kind of thing from among those you are ignorant of will you set before yourself to look for? And even if you happened exactly upon it, how would you recognize that this is what you didn't know? (Meno, 80d)

But as Socrates pointed out in reply, this argument is fallacious because (as he illustrates with an example from Geometry) we are sometimes capable of "recognizing" a truth, even when we are encountering it for the first time. Put another way, we already have some sort of "germ of truth" inside of us, which helps us to recognize greater truth when we stumble across it.

Plato called this human ability ἀνάμνησις (recollection), and proposed that it was due to having known the truth in a previous existence. But we don't need to take this Platonic myth too literally to recognize the essential point about learning. As Socrates says in this same dialogue:

I wouldn't strongly insist on the other aspects of the argument [the stuff about reincarnation], but that we would become better men and braver and less lazy if we believe it is necessary to search for what one doesn't know, rather than if we think that we can't discover what we don't know and should not look for it, for this I will fight strongly, if I am able, in both word and deed. (86d)

Thus, if we want to search for the true religion in a reasonable and open-minded way (rather than take religious disagreements as an excuse not to think for ourselves) then we need to avoid two opposite extremes:

- The first extreme would be if we make a list of all our opinions about highly controversial ethical topics (e.g. abortion, vegetarianism, alcohol, specific sexual taboos...) and demand that a religion can be true only if it agrees with us about each one of these particular issues. But this approach would absolutely preclude ever using religion to progress in our understanding of morality. .

It would, after all, be a very limited deity who didn't know anything more about the conditions for human flourishing than we do. And since people's views about morality evolve with time, it would be quite a coincidence if God's views happened to agree with e.g. early 21st century postmodern liberal mores in every single detail—even on points where we disagree with other places and times! (And even, with many other people who live in the same country as us.) Such an approach would only make sense, if I arrogantly assumed that I have nothing to learn from any being wiser than myself. . . - The opposite extreme—which is equally petrifying—would be to adopt a position of total moral helplessness, and take the attitude that we have no inherent knowledge of morality except for what we can learn through the dictates of some specific religion. But such total deference would make it impossible to use morality as a measuring-rod to help us determine which religion is true. After all, each religion will claim that its own moral system is right. So this sort of helplessness, is no better than moral relativism! .

Even if we start out in a religion which was truly revealed by God, this particular type of fundamentalism would actually prevent us from ever truly internalizing a moral system—as this requires, not just blind obedience, but also learning to appreciate how a particular way of life is healthy and good, at least for human beings like ourselves. .

A final and decisive objection is that it is simply incorrect!—in fact, human beings do have the ability to instinctively understand moral truths, in ways that are broadly similar; even if the details of how it expresses itself are modulated by our particular cultures and religious frameworks.

In summary, we should not expect our preconceptions to line up with every single teaching of a religion. But taken as a whole, it should come across as something clearly better than what we would have on our own.

We can rationally take our agreement/disagreement on a particular moral topic to be evidence for/against a particular religion. But, if we discover a religion which seems to have gotten many deep and important truths about humanity right, then we also need to take it seriously even when it makes claims that seem counterintuitive to us. (A rational person can take such claims "on the credit of the system", as St. John Newman memorably put it.)

Who is the Judge?

A closely related question is this: Do we come to religion with some degree of humility, and in the posture of someone willing to learn something new? Suppose we imagine assembling all of the `holy books' in the world, and looking through each one. How will we pick the morally best one?

If we come in the posture of a cynic, then we will be looking for something in the book which morally offends us. Once that happens, we will reject the book (unless somebody can convince us we were mistaken in doing so). In other words, we are coming to the book with the intention of judging God. Well, I cannot imagine any such person deciding to rank the Bible as the most moral of all religious books. Yes, there is some good stuff in there, but there is a considerable amount of weird and violent stuff. There are some inscrutable divine decrees, and several things which are foreign to modern sensibilities.

It is doubtful that such a person could be happy with any religion; but if they had to pick one, they'd probably be happier with some modernized religious community without much in the way of distinctive beliefs (like Unitarian Universalism, Reconstructionist Judaism, etc.)

On the other hand, we could also imagine somebody coming to a holy book as a penitent who needs spiritual healing, or as a confused person who wants wisdom. If I take this attitude, then I (as a morally imperfect person) am looking for the holy book that is most able to judge me, to show the ways in which I fall short and can do better. I want a book which can inspire me morally to a higher standard, and which illuminates the paradoxes and complexities which arise trying to live a spiritual life in the real world. If you are looking to be judged in this way, then I am not aware of any book which is better for this purpose then the Bible.

(Note that this approach is quite different from "total moral helplessness", since it still requires us to engage our minds! We still need to decide whether the holy book speaks to our condition; whether its moral critique is incisive or superficial; whether it is calling us to a higher stage of moral development, or a lower one which we have already superceded.)

In other words, your assessment of the Bible's ethics is going to depend in large part on what you are hoping to get out of it. As the Bible itself says in multiple places, "God opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble."

A Product of Its Time

What a true revealed religion should definitely not be, is simply a reflection of the prevailing ethics of the time and place in which the claimed prophet lived. There are lots of examples of ancient religious leaders prescribing barbaric acts, that were common in their era of history. But in some ways, this phenomenon is more hilariously obvious when the ethical system being hawked has only quite recently gone out of vogue.

As an example of this, consider the early 20th century internationalist modernism endorsed by Shoghi Effendi (the grandson and first successor to the main prophet of the Bahái religion):

The unity of the human race, as envisaged by Bahá’u’lláh, implies the establishment of a world commonwealth in which all nations, races, creeds and classes are closely and permanently united, and in which the autonomy of its state members and the personal freedom and initiative of the individuals that compose them are definitely and completely safeguarded.

This commonwealth must, as far as we can visualize it, consist of a world legislature, whose members will, as the trustees of the whole of mankind, ultimately control the entire resources of all the component nations, and will enact such laws as shall be required to regulate the life, satisfy the needs and adjust the relationships of all races and peoples. A world executive, backed by an international Force, will carry out the decisions arrived at, and apply the laws enacted by, this world legislature, and will safeguard the organic unity of the whole commonwealth. A world tribunal will adjudicate and deliver its compulsory and final verdict in all and any disputes that may arise between the various elements constituting this universal system.

A mechanism of world inter-communication will be devised, embracing the whole planet, freed from national hindrances and restrictions, and functioning with marvellous swiftness and perfect regularity. A world metropolis will act as the nerve center of a world civilization, the focus towards which the unifying forces of life will converge and from which its energizing influences will radiate. A world language will either be invented or chosen from among the existing languages and will be taught in the schools of all the federated nations as an auxiliary to their mother tongue. A world script, a world literature, a uniform and universal system of currency, of weights and measures, will simplify and facilitate intercourse and understanding among the nations and races of mankind.

In such a world society, science and religion, the two most potent forces in human life, will be reconciled, will cöoperate, and will harmoniously develop. The press will, under such a system, while giving full scope to the expression of the diversified views and convictions of mankind, cease to be mischievously manipulated by vested interests, whether private or public, and will be liberated from the influence of contending governments and peoples. The economic resources of the world will be organized, its sources of raw materials will be tapped and fully utilized, its markets will be cöordinated and developed, and the distribution of its products will be equitably regulated.

("World Unity the Goal", The World Order of Bahá’u’lláh [paragraph breaks added by me])

These words were written in 1936, and they are quite obviously a product of the time and place in which they were written. For anyone who has seen the rest of the 20th century, the idea of placing our spiritual hopes for the future in the hands of a more powerful version of the United Nations—which in turn imposes a monoculture on the rest of the world—is too absurd to contemplate as a potential divine revelation.

Obviously, no real divine revelation was needed to come up with this idea. Effendi (and to a lesser extent Bahá’u’lláh) were simply taking up the "spirit of the age"—what the internationalists and socialists of that time were already striving for—and recasting it as a principle of their own religion. But a universally valid moral system ought to transcend the prejudices of the particular time and place in which it was originally developed.

(The one somewhat prescient aspect of this passage is that humanity did indeed come up with a global "mechanism of world inter-communication": a.k.a. the Internet. Kudos for that. But the Internet is a highly de-centralized system, which allows for cultural diversity, and which certainly does not require a omnicompetent world-state in order to function. And as we are all now acutely aware, the Internet doesn't actually solve our moral coordination problems, it just transfers them to a new sphere.)

If what you care about most is maximizing ethical niceness, but you also want a religion which is a few centuries old (and thus not simply a repackaged version of contemporary morals) you could always try Sikhism—about which I know relatively little, but it seems to be one of the ethically nicer religions out there (notwithstanding being the religion of a warrior caste). However, I haven't been able to get much out of reading its holy book (the Guru Granth Sahib) at an intellectual level, as it mainly seems to repeat the same basic ideas over and over again. Probably the point is not so much to be intellectually stimulated but to absorb the main idea by singing it over and over again. But, I suppose that is the sort of benefit that one would only get by actually joining a religion...

II. Christianity

So is there a system of religious ethics which does transcend its particular time and place, sufficiently to be credible as having a transcendental origin?

Surprisingly, Jesus' moral teaching, as recorded in the Gospels, e.g. the Sermon on the Mount, actually passes this test. [If you've never read it before, stop and read the whole thing right now, starting with "Blessed are the poor in spirit" in chapter 5 and ending at the statement of the crowds being astonished by his teaching at the end of chapter 7.] It is still an impressive spiritual standard, still relevant even after 2,000 years of humanity's moral development, and it has inspired even non-Christian activists such as Gandhi to greater moral heights.

(The Sermon does contain a few minor cultural references to religious institutions of the time; for example Jesus mentions the practice of offering gifts to the Temple at Jerusalem, and also the Sanhedrin which was the supreme court for religious practice in Israel. But it seems clear that all these references are inessential to the basic principles Jesus was preaching.)

Jesus cuts away the legalism common to many religious traditions, and puts the focus on integrity in the heart:

You have heard that it was said to the people long ago, `You shall not murder, and anyone who murders will be subject to judgment.' But I tell you that anyone who is angry with a brother will be subject to judgment. Again, anyone who calls his brother ‘Raqa’ [Empty-headed] is answerable to the Sanhedrin, but anyone who says, ‘fool!’ will be in danger of the fire of hell.

Therefore, if you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to them; then come and offer your gift. (5:21-24)

In other words, if you want to be righteous, it's not sufficient to just not kill people. Even somebody who doesn't express their hatred in words, may be murdering their brother in their hearts (many times over), and that contempt comes out in the words we use to speak about other people. So if you want to cut to the root of the matter, you have to begin with the way you regard others in your mind.

The same sort of deepening applies to the other commandments as well:

You have heard that it was said, `You shall not commit adultery.' But I tell you that anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart!...

It has been said, ‘Anyone who divorces his wife must give her a certificate of divorce.’ But I tell you that anyone who divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, makes her the victim of adultery, and anyone who marries a divorced woman commits adultery.

Again you have heard that it was said to those of old, `You shall not swear falsely, but shall perform your oaths to the Lord.' But I say to you, do not swear at all... Let your ‘Yes’ be ‘Yes,’ and your ‘No,’ ‘No.’ For whatever is more than these is from the evil one.

(5:27-37, excerpts)

Jesus' radical new interpretation of the Torah shows us the real source of misdeeds—our own desire to get what we want, even at the price of manipulating others. They show that no amount of following of technical justifications—"it's okay that I left my wife for another woman because I filled out the proper legal paperwork"; or "I don't have to keep this promise because I didn't swear I would do it"—can prevent us from doing wrong. Instead, we need for our own internal motivations to be right.

Beyond Legalism: Children, not Slaves

Most religions tend to focus on regulating externals of behavior. They are obsessed with figuring out the answer to the question "What is the minimum acceptable standard of behavior?" This process tends to produce an elaborate law-code, often (as in the case of rabbinic Judaism) becoming more and more complex with time.

But Christianity says that God doesn't want slaves, who obey mindlessly out of fear, without knowing the reasons why. It is true that his awe-inspiring glory deserves our worship and submission. Yet the New Testament says he wants to treat us as his adult children (who can be trusted with freedom after learning what is good) and as his close friends (who know his plans and thoughts). As far as I know, this attitude is unique among theistic religions. It would be quite presumptuous, if God had not taken the initiative by drawing near to us, in order to share the mind of his Spirit with us. Yet now that I have been granted these privileges, giving them up again in order to serve a more distant deity would be disappointing. To draw back from this intimacy, from the thoughtful responsibility he has entrusted me with, seems more like immaturity than humility.

Love your Enemies

When Jesus goes on to say:

But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well. If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles. Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you.

You have heard that it was said, ‘Love your neighbor and hate your enemy.’ But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. (Matthew 5:39-45),

these sayings are far from trivial to implement, yet actually this is the only practical suggestion—the one that actually works in practice, e.g. in the Civil Rights movement in America—for creating peace between those who hate each other, other than wiping one of the groups out.

Christians have differed as to whether Jesus' words imply total Pacifism (I don't think so myself), but I do think that these words introduce us to a nonviolent form of power which, when applied intelligently, is far greater than the power of violence; because it has the power to move people to freely become better, in a way that no amount of external coercion can ever do.

America's greatest 20th century political activist, St. Martin Luther King Jr., explained the meaning of this passage as follows:

The ultimate weakness of violence is that it is a descending spiral begetting the very thing it seeks to destroy, instead of diminishing evil, it multiplies it. Through violence you may murder the liar, but you cannot murder the lie, nor establish the truth. Through violence you may murder the hater, but you do not murder hate. In fact, violence merely increases hate. Returning violence for violence multiplies violence, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that.

These words are not mere idealism, as in: wouldn't it be nice if people behaved this way, but we know they never will. For King, these words described a highly practical strategy for social change. He had hands-on experience using Jesus' method to reform the segregationist South. Of course, King also paid the price for it. It can be seen from this example that nonviolence does not imply submissively accepting the status quo; rather it is a creative way of seeking justice by appealing to people's better nature.

As far as I can see, Jesus' radical ethic of love, forgiveness and acceptance is morally better than anything else on offer.

I do not of course mean to imply that the ethical duty to love one's enemies was absolutely original in all respects when stated by Jesus. It was anticipated by Plato, and certain parts of the Hebrew Bible, although Christ emphasized it more forcefully. The point is not so much that it was utterly new, but that it was right, even though it was not a truth generally appreciated in Jesus' culture, nor indeed in any culture not influenced by Christianity. (Sometimes I'm not too sure about Christians either!)

Two Potential Stumbling Blocks

Although it should be indisputable from the above that Jesus' ethical teaching calls his followers to an extremely high ethical standard, there are still a couple of ways in which his morality might still seem alienating or "bad" to many nonreligious readers. It is worth highlighting these issues briefly, although each would really justify a long post of its own:

Road Bump #1: God the Father

The first point is that Christianity is unavoidably and distinctively theistic, through and through. Without denying that there are some aspects of Jesus' teaching which could be applied with profit by non-religious people, much of what he says simply makes no sense, when separated from the idea of a God whose character we can count on. Even when Jesus announces a moral rule that atheists might be able to get behind, he nearly always appeals to theological reasons—for example, imitating the character of God—to explain why the rule should be followed.

I have seen pastors who tried to put forward Jesus' teachings as a sort of "worldly wisdom" that can be appreciated and put into practice even by those who aren't yet religious. But, apart from a few tidbits, I'm not sure this approach is a very coherent way of introducing seekers to Christianity.

The fact is, it makes no sense to give up your earthly life and goals for the sake of eternal happiness, if in fact there is no God to take care of us, and to keep his promises, and to be blessed by being in communion with him. Anyone who wants to "try it out", will quickly see that Jesus' commands cannot be separated from Jesus' teaching about our generous and kind Father, whom we are urged to trust to provide for our needs:

“Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives; the one who seeks finds; and to the one who knocks, the door will be opened.

Which of you, if your son asks for bread, will give him a stone? Or if he asks for a fish, will give him a snake? If you, then, though you are evil, know how to give good gifts to your children, how much more will your Father in heaven give good gifts to those who ask him!" (Matthew 7:7-11)

This does not necessarily mean that an agnostic cannot begin to try to obey some of Jesus' teachings—but I do not see how they could possibly do so, without at least hoping or wishing that a God like this exists, and that following Jesus' teaching might put them in some kind of relationship with something like this deeper reality that Jesus called Father.

Given that we are currently evaluating different forms of religious ethics, this is only to be expected. If you do not yet currently believe in a God, then understanding Jesus' teaching will require you to imaginatively "suspend your disbelief" on this point. There is no point in taste-testing a religion for its ethical truth, if you aren't prepared to grant, at least hypothetically, its most essential premise.

Having granted this premise, what is most distinctive in Christianity is not just whether we believe in God, but rather than nature and character of the God being described, and the way in which his goodness can be taken as a model to transform our own lives.

The second potential road-block is this:

Road Bump #2: Final Judgement

A second, more sensitive issue, is the fact that Jesus repeatedly warns people about the fact that there is a final judgment coming at the end of history, and that even though God loves us, it is quite possible—in fact easy, if a person takes no care to avoid it—for that person to be condemned to Hell. This is a feature which is bound to seem unpalatable to anyone who doesn't feel that their degree of guilt (or perhaps, anyone's guilt) would warrant such a stiff sentence. And of course, the higher the moral standard we are expected to uphold, the scarier these threats are.

As Bertrand Russell argued:

There is one very serious defect to my mind in Christ’s moral character, and that is that He believed in hell. I do not myself feel that any person who is really profoundly humane can believe in everlasting punishment. Christ certainly as depicted in the Gospels did believe in everlasting punishment, and one does find repeatedly a vindictive fury against those people who would not listen to His preaching—an attitude which is not uncommon with preachers, but which does somewhat detract from superlative excellence. You do not, for instance, find that attitude in Socrates. You find him quite bland and urbane towards the people who would not listen to him; and it is, to my mind, far more worthy of a sage to take that line than to take the line of indignation. (Why I am not a Christian)

Of course, belief in post-mortem punishment is far from unique to Christianity. Any religion which believes in both human freedom and life after death, necessarily has to grapple with the question of what happens to people who sink into a self-chosen state of moral corruption. Even most Buddhist sects believe in various hells (generally regarded as finite, but astronomically long, in duration).

A complete discussion of the topics of Heaven and Hell goes well beyond the subject of this blog post, the purpose of which is not to share my own personal ideas about how this theology could be justified. One could note however that the possibility of damnation would seem to be logically inherent in any theological system which satisfies the following criteria:

- All humans will live forever;

- It is impossible for humans to be happy forever without loving God;

- God does not force humans to love him, if they choose not to.

On these premises, if anyone would prefer to be immoral (and thus unhappy) rather than to love God, then there does not seem to be any obvious alternative to a system of indefinite incarceration, for those who reject Heaven.

The Offer of Grace

What is unique to Jesus' teaching, is the extent to which these warnings are side-by-side with the most forceful declarations of God's mercy and grace towards sinners:

What do you think? If a man owns a hundred sheep, and one of them wanders away, will he not leave the ninety-nine on the hills and go to look for the one that wandered off? And if he finds it, truly I tell you, he is happier about that one sheep than about the ninety-nine that did not wander off. In the same way your Father in heaven is not willing that any of these little ones should perish. (Matthew 18:10-24)

We do not have to be saved by our own efforts; instead the Good Shepherd comes looking for his lost sheep in order to save it. Jesus welcomed the prostitutes and the dishonest tax collectors, because God is a loving Father whose heart goes out to all his children, no matter what they have done. God doesn't want anyone to perish, but for everyone to come to him and be saved.

If anyone is outside the scope of God's forgiveness, it is not because God runs out of patience and kindness, but rather because that person is trapped in their own hatred and failure to forgive others. In other words, the only unforgivable sin is to reject the Holy Spirit, even when he makes his goodness clear to you. All who repent and turn to Christ can be saved, no matter what they have done.

Not "Meek and Mild"

Jesus' own ways of reaching out to people were highly controverisial. Shockingly for the time, he took women on as close disciples. He was criticized for going to parties with notorious sinners, for healing people on the Sabbath, and for telling religious people that their hypocrisy was an abomination in God's eyes. As he himself noted, a life of real virtue leads to persecution.

They also accused him of blasphemy, for saying things which sounded as if he was claiming some sort of equality or association with God himself. (This is also something which we have to come to terms with in deciding what Jesus really was, since as many people have pointed out, if he was wrong that would make him a delusional megalomaniac.)

I remember reading the Gospel of Matthew for the first time as a child and being surprised by the continual extremeness of Christ's teachings. My parents are devoted Christians and I was very pious, so you would think I would already have known what to expect, but still—the words of Jesus were shocking. It seemed appropriate that Christ's words were typed in red ink in my mother's Bible, as if they were going to burn through the page like acid. As St. Chesterton wrote in The Everlasting Man (a rethinking of comparative religion from a Christian perspective):

A man reading the Gospel sayings would not find platitudes. If he had read even in the most respectful spirit the majority of ancient philosophers and of modern moralists, he would appreciate the unique importance of saying that he did not find platitudes. It is more than can be said even of Plato. It is much more than can be said of Epictetus or Seneca or Marcus Aurelius or Apollonius of Tyana. And it is immeasurably more than can be said of most of the agnostic moralists and the preachers of the ethical societies; with their songs of service and their religion of brotherhood. The morality of most moralists ancient and modern, has been one solid and polished cataract of platitudes flowing for ever and ever. That would certainly not be the impression of the imaginary independent outsider studying the New Testament. He would be conscious of nothing so commonplace and in a sense of nothing so continuous as that stream.

He would find a number of strange claims that might sound like the claim to be the brother of the sun and moon; a number of very startling pieces of advice; a number of stunning rebukes; a number of strangely beautiful stories. He would see some very gigantesque figures of speech about the impossibility of threading a needle with a camel or the possibility of throwing a mountain into the sea. He would see a number of very daring simplifications of the difficulties of life; like the advice to shine upon everybody indifferently as does the sunshine or not to worry about the future any more than the birds. He would find on the other hand some passages of almost impenetrable darkness, so far as he is concerned, such as the moral of the parable of the Unjust Steward. Some of these things might strike him as fables and some as truths; but none as truisms. For instance, he would not find the ordinary platitudes in favour of peace. He would find several paradoxes in favour of peace. He would find several ideals of non-resistance, which taken as they stand would be rather too pacific for any pacifist. He would be told in one passage to treat a robber not with passive resistance, but rather with positive and enthusiastic encouragement, if the terms be taken literally; heaping up gifts upon the man who had stolen goods....

The statement that the meek shall inherit the earth is very far from being a meek statement. I mean it is not meek in the ordinary sense of mild and moderate and inoffensive. To justify it, it would be necessary to go very deep into history and anticipate things undreamed of then and by many unrealised even now; such as the way in which the mystical monks reclaimed the lands which the practical kings had lost. If it was a truth at all, it was because it was a prophecy. But certainly it was not a truth in the sense of a truism. The blessing upon the meek would seem to be a very violent statement; in the sense of doing violence to reason and probability....

Something of the same thing may be said about the incident of Martha and Mary; which has been interpreted in retrospect and from the inside by the mystics of the Christian contemplative life. But it was not at all an obvious view of it; and most moralists, ancient and modern, could be trusted to make a rush for the obvious. What torrents of effortless eloquence would have flowed from them to swell any slight superiority on the part of Martha; what splendid sermons about the Joy of Service and the Gospel of Work and the World Left Better Than We Found It, and generally all the ten thousand platitudes that can be uttered in favour of taking trouble—by people who need take no trouble to utter them.

("The Riddles of the Gospel", in The Everlasting Man)

But if Christ really came down from Heaven, you might expect him to teach a morality which is of a different nature than any Earthly cultural code. Just as if you were sent back in time thousands of years to the ancient world, you would inevitably react with dismay at many atrocities which the ancients took for granted; so too Jesus preached just as if he came from another world, where life operates on completely different lines than what we Earthlings are used to.

Humble Service

Another of these paradoxes was Jesus' idea about the nature of leadership. To the first leaders of his Church, he says:

“You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you! Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be your slave—just as the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (Matthew 20:20-28)

And here the Theology of Christianity—that God sent his Son to forgive his enemies and save us from destruction—is in perfect consonance with the Ethics. Jesus' actions were not hypocritical; he lived a life (and died a death) of self-sacrifice and forgiveness. Healing the sick and crazy, welcoming social outcasts and telling them their sins were forgiven, feeding the hungry, raising the dead, preaching the good news to the poor. Jesus' character makes the commonplace seem miraculous and the miraculous commonplace.

It is certainly true that the doctrine of the Atonement—that Jesus' innocent victimization on the Cross is the method by which God forgives our sins—can be perplexing and disconcerting, when considered from the point of view of ordinary human justice, especially if it is explained using inapt metaphors.

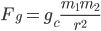

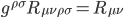

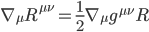

If your notion of the divine does not allow for elements of mysterious depth, if you insist that nothing can transcend your own understanding, then I have no way of getting you past this third potential stumbling block. All I can say is that a supposed divine revelation would be quite impoverished indeed if it contained nothing strange or difficult. When we study subatomic matter, out of which we ourselves are made, we find the bizarre mind-bending paradoxes of Quantum Mechanics, which can be described mathematically but nobody can agree on what's going on metaphysically. It would be strange indeed if our interactions with God—a being coming in from outside our physical world entirely—did not have a comparable degree of weirdness!

A Spiritual Kingdom

Finally, Christianity says that Jesus conquered death itself at his Resurrection from the grave. He did not meet the Jewish expectations of a world revolution, but he did something greater, triumphing over all the strong things in the world with his tender weakness. That is why he proclaimed that the kingdom of heaven was very near, and would be a revolution in the hearts and minds of anyone willing to be born anew, in order to enter it with humility, like a small child.

If this did not happen and—as some believe—the Messiah is yet to come, can he possibly be greater than this? After Jesus, anyone else would be an anticlimax. Even if you were to write a fictional story to try to imagine a superior Messiah, the only way you could make your fictional Messiah morally satisfying is by including enough elements of Jesus' character, that the story would really owe its emotional and moral depth to him. (Or one could simply accept the moral retrogression back to the military leader trope, as is largely the case in e.g. the Dune mythos. This leads to a satisfying story for a novel, but if it happened in reality, it would not answer the deepest spiritual needs of the human race.)

Christians believe that Jesus' teaching is the Way (the Tao) which comes down from Heaven. Unlike the Torah or the Quran, the New Testament contains no instructions for setting up an earthly theocratic government; instead it is a spiritual kingdom:

Jesus said, "My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest by the Jewish leaders. But now my kingdom is from another place." (John 18:36)

Therefore, his followers have no excuse for engaging in religious persecution on Earth.

Jesus and Hypocrisy

Although many have tried. Let me say right away that I do not consider any religion to be refuted merely by the hypocrisy of those who come in later generations. I am asking how glorious the original teachings are, not how well they have been followed. Christians, like others, are frequently hypocrites. In fact, one might well expect the religion with the highest ethical standards to provide the greatest temptation to hypocrisy, since those are the standards which are hardest to live up to. So when people complain about how the Church is full of hypocrites, they thereby testify that they know that the Christian standards are (at least in certain respects) good and right. We don't usually complain when people fall short of a religious standard which we don't approve of!

And if you hate hypocrisy, bear in mind that you probably owe this very insight to Jesus' teaching. Just as the weekend comes from the Judaeo-Christian practice of Sabbath keeping, so the modern Westerner's sensitive conscience on this point comes, directly or indirectly, from the New Testament. There is no religious text which speaks more forcefully against hypocrisy. Jesus' denunciations of this sin were spectacularly harsh. And yet his severity was clearly needed, given the later conduct of many of his own followers.

Because these warnings are in the DNA of the Christian Church, it can never remain permanently fossilized in legalism and spiritual decay. There will always be a revival. If you are sincerely worried about becoming a hypocrite yourself, and if you want to pick the religious teacher most likely to prevent you, if you follow him sincerely—surely, Jesus is the one.

(Although, I can't help but notice that the people who complain about religious people being hypocrites, seldom seem all that worried that they might be hypocritical in other respects. Shall we coin a term and call that "meta-hypocrisy"?)

Of course, hypocrisy is not at all the same as simply not living up to one's own moral standards. Otherwise there would be no difference between the self-righteous Pharisee and the repentant tax-collector! We all fail to live up to what morality requires, but some people sincerely repent of it, while others don't care or try to pretend everything is okay. If you ever find a religious group which succeeds in keeping their own moral standard, you should run away from them as fast as you can! Because if they can meet it, it must be abysmally low. At least if people fall short of the standard they set by their preaching, they leave open the possibility of repenting and doing better in the future.

Other Religions

The moral teachings of other religions, might indeed have been improvements on what went before, but are limited and defective in comparison with Christianity. I don't mean of course to imply that there's nothing ethically good in other religions. But they don't impress and amaze me, to the same degree that Christianity does.

III. Judaism

Although Christians believe the Torah to be genuinely revealed by God, even this must be regarded as "limited", since according to Christianity it is incomplete in nature, and its ceremonies pointed the way to something better, to come later. Since Christianity came from Judaism, a Christian cannot consistently say that the core ideas of Jewish ethics were mistaken. But, we can point to the place where Jewish ethics has reached its highest point of fulfilment, which is in the teachings of Jesus.

But first, what is the most distinctive feature of Jewish ethics? One of the main innovations of Judaism was the unification of religion and morality. God is believed to be both righteous himself, and the one who demands righteousness on Earth.

In paganism, the concepts of sin (that which offends God) and moral wrongdoing (injustice) can come apart; an act may please one god and yet offend another. But in Jewish theology, sin and wrongdoing are coextensive: one can never offend God by a righteous act nor please him by a wicked one. To be sure, the implication goes in both directions, meaning that a Jew might sometimes need to submit to a difficult divine command, the reasons for which are obscure. But it is always implied that when this is so, the moral limitation lies with us humans, rather than with God. Hence, obedience is itself a righteous act, and is never merely a craven submission to a more powerful being, as in much of paganism.

Before anyone marches in with a Dawkins-esque caricature of the "God of the Old Testament", let me say right away that there is simply no comparison here to the moral universe of pagan mythology. Not even the most hardened blasphemer would deny that the God of the Bible is at least moralistic in his character. He is always portrayed as actively defending moral norms, with acts of justice or mercy. When a reader objects to one of the Old Testament God's verdicts, they usually do so for one of three reasons [not all of which are applicable to each case]: (1) because the punishment seems too harsh, or (2) involves collective justice on groups, or (3) involves offenses against archaic codes of conduct which we no longer accept. In a certain Nietzschean sense, one might say that the biblical God is more frequently accused of an excess of morality (at least in the sense of punishing sins), rather than a deficit of morality. But the God of the Old Testament does not ever simply disregard morality to gain personal advantage; nor does he, like Zeus, commit adultery with his neighbor's wife and then turn her into a animal to cover up his hijinks. In this sense the Hebrew tradition, even at its most distressing, can be objectively seen to reside on a higher moral and metaphysical plane than pagan polytheism.

And it should be noted that the Israelites themselves, comparing their beliefs to others, did not view their own God as being especially implacable in wrath. Rather, they characterized him as a "gracious and merciful God, slow to anger and abounding in love, a God who relents from sending calamity" (Jonah 4:2).

A critic might say that, simply by asking the question which religion is morally good, we are already begging the question massively in favor of Judaism and its offshoots, since it was Judaism that popularized this idea in the first place.

And yet none of us can completely transcend our roots. When Western skeptics critique the moral sensibilities of Jewish scriptures, they are usually doing so on the basis of moral assumptions which they learned, indirectly, from Christianity. Since Christianity is deeply rooted in Judaism, this really means that their ammunition against Judaism comes indirectly from sources within Judaism itself. Had Judaism and Christianity never existed, it is quite probable that most modern "civilized" people would have no concept of universal human rights. Hence: less emphasis on protection of the weak and victimized, more tolerance for barbaric practices like slavery, torture, and gladiator fights, etc. There have been plenty of civilized pagan cultures (Greeks, Romans, Chinese, Japanese) in which these concepts have not played a major role.

(This does not mean that there were no ways that e.g. Greco-Roman pagan religion intersected with morality. There were a few specific moral violations that were viewed as likely to be punished by the gods, such as violations of hospitality or oaths, or violence against parents. And of course, Egyptian polytheism eventually developed some very precise notions of divine judgement in the afterlife. But for the most part, appeasing the gods was regarded more as a practical necessity, than a moral one. For a good overview of the way that most pagans in the Roman Empire viewed their religious rituals—which had very little in common with what most modern people would regard as "spiritual"—see this excellent blog series by a very entertaining historian.)

Proceeding to more specific observances, there are indeed many parts of the Torah which are still very morally inspirational today, such as the Ten Commandments, or the laws about ensuring justice and mercy for widows, orphans, and strangers:

Do not deprive the foreigner or the fatherless of justice, or take the cloak of the widow as a pledge. Remember that you were slaves in Egypt and the Lord your God redeemed you from there. That is why I command you to do this.

When you are harvesting in your field and you overlook a sheaf, do not go back to get it. Leave it for the foreigner, the fatherless and the widow, so that the Lord your God may bless you in all the work of your hands. When you beat the olives from your trees, do not go over the branches a second time. Leave what remains for the foreigner, the fatherless and the widow. When you harvest the grapes in your vineyard, do not go over the vines again. Leave what remains for the foreigner, the fatherless and the widow. Remember that you were slaves in Egypt. That is why I command you to do this. (Deut 24:17-22)

When looking at passages like this, we can indeed agree with the Psalmist that:

The judgments of the LORD are true, being altogether righteous. They are more precious than gold, than much pure gold; they are sweeter than honey, than honey from the comb. (Psalm 19:9-10)

Yet, although much in the Torah is splendid and righteous, and many of its ceremonies seem beautifully significant, other provisions are difficult to justify except as concessions to the prevailing culture—as in the case of divorce, where Jesus justified his own teaching on the subject by saying that "Moses permitted you to divorce your wives because your hearts were hard. But it was not this way from the beginning" (Matt. 19:8).

It is then, an option for a Christian to critique other morally repugnant provisions in the Torah, as making similar allowances to the barbaric conditions of the time, rather than being perpetually prescriptive norms. Such provisions might include e.g. the rules allowing warfare to be waged against civilians (Deut. 20:10-15), the rules allowing Israelites to buy non-Israelite slaves (Lev. 25:44-46, but cf. Deut 23:15-16 for a contrasting rule concerning refugees), and indeed the subordinate position of women in a patriarchal society (not that this is a major topic of legislation in the Torah, it's more that it's taken for granted).

Of course this raises questions for Christians (like myself) who believe that these commandments were revealed by God to Moses. It might be possible to justify these legal provisions as "perfect" in the limited sense that it these were the best set of laws that could be given to the Israelites at the time God gave them. However, there's been considerable moral progress since then. Thus—although it remains in the Christian Bible as a perpetual record of God's past guidance to his people—in its literal application, the Torah is simply no longer a contender for the best moral code for humanity.

(Given Christian ethics, the hardest commandment in the Torah to defend is probably the order to wipe out the Canaanite tribes. Now defending genocide is one of those things that is no longer quite so respectable as it used to be, and rightly so! Nevertheless, I tried my hand here at explaining several ways in which this divine command is meaningfully different than what e.g. Hitler did.)

Turning to Judaism in its modern rabbinic form, it is still somewhat racially narrow, and often more concerned with technical legalistic observances than with the heart. After the destruction of the Temple, the Pharisees—the spiritual ancestors of modern day Rabbinic Judaism—reformed and modernized their religion, but also took many liberties of interpretation, some of which are staggering in their perverseness. For example, the Pharisees interpreted Exodus 23:2:

Do not follow the crowd in doing wrong. When you give testimony in a lawsuit, do not pervert justice by siding with the crowd.

as implying the right of a majority of rabbis to effectively (re)interpret Scripture, even though the literal meaning of the text specifically says not to follow the majority in doing wrong.

Of course, this rabbinic flexibility does allow for religious mores to be progressively updated in response to social changes, but it also tends to produce a game in which each new rule spins off an increasingly complex chain of further legislation via interpretation. Since this process has been going on for thousands of years, the results can get very strange.

For example, the rabbinic prohibition on mixing milk with meat somehow emerged from the Torah commandment: "Do not cook a baby goat its mother's milk" (a better generalization might be: Don't be a jerk to beings that are totally in your power). This in turn spun off the additional rule to keep separate dishware for meat and dairy, and so on. Then one identifies various loopholes, allowing you to get around certain rabbinic rules when they become too onerous, and so on. All of this seems like a major distraction from actual ethics and spirituality.

Although, taking a more positive point of view, there is a certain attractiveness (at least in an outsider's view) of an Orthodox Jewish piety; in which minute decisions are continually referred back to the Talmud and to divine law; so as to dedicate the smallest mundane details of family life to the service of a Name that is too sacred to even be spoken out loud. From the Christian perspective, this is indeed very instructive as an image of what the word "holiness" means, total dedication to God. But to take such a lifestyle as a matter of obligation differs from the Christian relationship to God which is based more on the guiding presence of the Holy Spirit than in following a particular code of laws.

Another positive effect of all these rabbinic disputations, which should probably be mentioned, was to produce a culture of vibrant intellectual debate. Even separated from its original religious matrix, this culture of questioning seems to persist in the case of secular Jews. This is one possible explanation for the enormous Jewish impact on philosophy, science, and culture (far exceeding what one would expect from the total Jewish world population).

IV. Zoroastrianism

In Zoroastrianism, the commandments seem to be more concerned with ritual purity than with ethics, to a far greater extent than in Judaism. Yes, honesty and fair-dealing are considered important, but the most important rules concern things like burial practices and hygiene codes.

While I don't think these punishments are enforced in modern times: in the Venidad (part of traditional Zoroastrian scripture), many purely ceremonial offenses are considered worse than murder, and are punishable by being flogged with hundreds or even thousands of lashes of the whip. Unforgivable sins (those which cannot be expiated with any amount of punishment) include: burying the corpse of a man or dog, homosexuality, and voluntarily committing "the unnatural sin" [masturbation, according to some translators]. For these acts there can be no atonement whatsoever! (At least for those who are already members of the religion. Those who converted, back when that was a thing that happened, apparently got a pass, as long as they promised never to do it again. Though nowadays, I imagine that most of these rules about punishments aren't seriously practiced.)

Zoroastrians are Dualists: they believe the world was made by two gods, one of them good and the other evil. Unlike the Judaeo-Christian worldview, which affirms the essential goodness of creation, Zoroastrianism teaches that certain aspects of Nature were created by the Devil, and are inherently evil and impure. For example they believe that cats were created by the Evil God, while dogs were created by the Good God. Therefore it is considered is a righteous deed to kill cats, but a grievous sin to kill a dog. Speaking as a cat person, I think this is pretty clearly drawing the line between good and evil in the wrong place! It is simply not ecologically or ethically sound to simplistically divide animal species into "good" and "evil", as if we lived in a children's animal fable. Even if there is a good case to be made for fewer bloodsucking mosquitoes!

(Islam has a completely different take on this, as Mohammad seems to have also been a cat person.)

However, Zoroastrians also strongly emphasize the importance of free will, and the ability of rational creatures (even the gods!) to choose between good or evil. There is even an amusing Zoroastrian legend that the Devil created the Peacock just to prove that he could make something good, if he wanted to.

(Oddly, this is not the only Devil-Peacock connection one comes across in comparative religion. The Yazidi venerate the "Peacock angel" Melek Taus, whom they identify with Iblis—an Arab word for the Devil. In the Quran, Iblis refuses God's command to prostrate himself before the newly created Adam, and as a result loses his position as chief over the angels. But in Yazidi mythology, Iblis refuses to venerate Adam out of a misguided loyalty to God, and he is eventually restored to his former position as the most exalted manifestation of God's glory. Needless to say this belief, easily confused with a more malign Satanism, has led to considerable misunderstandings with the surrounding Muslim cultures, and the Yazidis have suffered many severe persecutions, most recently under ISIS.)

So, if you want to think of yourself as a participant in an epic battle between good and evil, Zoroastrianism is a pretty cool religion. But the lines between good and evil are drawn in some pretty arbitrary seeming places. I don't really see much ethical wisdom here which can't be obtained more easily from Judaism (plus Judaism actually accepts converts if you ask persistently enough).

V. Islam

The Islamic religion preaches racial harmony, generosity to the poor, and sincere piety. In the tradition of Ethical Monotheism, the Quran proclaims that God is firmly on the side of moral behavior and fair conduct:

God commands justice, doing good, and generosity towards relatives and He forbids what is shameful, blameworthy, and oppressive. He teaches you, that you may take heed. Fulfil any pledge you make in God's name and do not break oaths after you have sworn them, for you have made God your surety: God knows everything you do. Do not use your oaths to deceive one another—like a woman who unravels the thread she has firmly spun—just because one party may be more numerous than the other. God tests you with this, and on the Day of Resurrection He will make clear to you the things you differed about. (Haleem translation, Sura 16:90-92)

On the other hand, the Quran does not pass modern standards for the treatment of women. It permits the sexual exploitation of women through slavery, polygamy, and easy divorce; and in several cases its laws discriminate explicitly against females, e.g. Sura 2:282, which considers the testimony of two women equivalent to one man. (Although Mohammad must be given credit for banning infanticide against female babies.)

In the Hadith, Mohammad legislated the death penalty for apostates (those who stop believing in Islam). And in numerous passages, the Quran encourages warfare and violence against pagans and those viewed as enemies of Islam, sanctioned by reward and punishment in the afterlife:

God has purchased the persons and possessions of the believers in exchange for the Garden [i.e. Paradise]—they fight in God's way; they kill and are killed—this is a true promise given by him in the Torah, the Gospel, and the Quran. Who could be more faithful to his promise than God? So be happy with the bargain you have made, that is the supreme triumph. Those who turn to God in repentance; who worship and praise Him; who fast, bow down and prostrate themselves; who order what is good, forbid what is wrong and observe God's limits. Give glad news to such believers. It is not fitting for the Prophet and the believers to ask forgiveness for the idolaters—even if they are related to them—after being shown that they are the inhabitants of the Blaze [i.e. Hell]. (Haleem, Sura 9:111-113, brackets are my own added interpretation)

It is certainly possible to exaggerate the extent to which the Quran commands religious warfare. There are also some passages which advocate for peace (although many of these were from the early stages of Mohammad's ministry, leading some Muslim scholars to argue they were abrogated by later revelations). But no one can deny that warfare is a frequently recurrent theme; even if the applicability of these verses to the modern day is, of course, a matter on which different Muslims have many different opinions.

The time has long passed when I last had the experience of finding a new book in my Bible. If the voice that spoke in the Quran, had been the same voice that speaks to me in the Bible; if it had wooed me with divine paradoxes that call out to the depths of the spirit, cutting through all my excuses like a sword, and dazzling me with the promises of hidden glory; then I think I would have gladly listened to it, even if the price it asked me to pay (leaving behind my own family's religious convictions, and joining a new community) was high.

But as I see it, the Quran is not even trying to reveal a paradoxical reality or an awe-inspiring ethical code; it is really just a kind of civilization-building compromise; a simplification which attempts to combine the universalism of the Christian message with some of the ritualism of the Jewish system. Despite the intense focus of the Quran on the rewards and punishments of the afterlife, Mohammad's kingdom was very much of this world; therefore his followers do fight.

Despite being later in time, Islam does not uphold nearly as bracing a moral standard as Christianity, and it is arguable whether it is even a moral improvement on the Torah. In this respect it appears to be a moral retrogression—which might be justifiable if it had been intended for a limited cultural setting, but it is a severe problem in a supposedly final revelation for all humanity until the Day of Judgement.

Even Muslims can see that much of the legislation in the Quran is merely concerned with being good enough, setting a minimum standard of decency for what had previously been a barbaric time and place. As one thoughtful Persian argued in a medieval debate with a Christian:

I have said, I say and I will say that good and beautiful is the Law of Christ and much better than the earlier Law, but that mine [the Quran] is superior to both. Therefore consider what I am going to say, you may hear something that you do not condemn altogether. Your law, I say, is beautiful and good, but it is very hard and very burdensome and can not easily be useful. These remedies are too bitter to taste. So there is no error in believing it is not completely perfect. The Law of Mohammed follows the middle path and proclaims ordinances which are bearable and in sum gentler and more humane. Hence it is moderate in all respects and takes precedence over other laws. Indeed, the shortcomings of the old Law it fills by the supplements which it brings; on the other hand it reduces the exaggerations of the Law of Christ. There is also what it prunes visibly from both Laws, and suddenly it quite prevails over them.

It also avoids, I think, the mediocrity and the imperfection of the Law of the Jews on the one hand, and on the other hand, the elevation and height of the precepts of Christ, their harshness, that they are excessive and impractical so far for men, because they force, so to speak, our terrestrial nature to mount up to Heaven. It thus avoids both faults and strives for moderation in everything. Thereby it appears better than all the Laws that have preceded it.

The virtues, you know, consist of avoiding excesses and keeping exactly to a happy medium. That’s what we call virtue, and what virtue is. What is virtue is a happy medium, and what is not such is not virtue. This is the doctrine of all the ancients, and you yourself have said the same earlier.

But tell me, is it to stay in the happy medium—'to love one's enemies, to pray for them', to provide them with food when they are hungry;—And what is amusing—allow me this freedom—to 'hate his parents and brothers and even his own soul;—'to he who took your shirt, to give him also your coat';—'to give without distinction to he who asks' until you appear more naked than a stick and ridiculous in the eyes of those who would then make your property the loot of the Mysians, by pretending to be in need;—to he who strikes 'on one cheek, to turn the other; to never stand up to evil';—to have 'no stick, no bag, no money, nor two tunics';—‘to not worry about tomorrow’? "Who is the man of iron, diamond, more insensible than stone, who will bear all these things,—who will bear the offence and cherish the insulter;—who will do good to he who is ill-disposed towards him;—who by his extra bounty will invite the people of this species to gorge on him like vultures on the corpses of the dead?

[We should probably make allowances for the fact that this debate was hosted by Christians, and recorded by them, so that the Persian scholar might not have felt free to attack Christianity in the strongest possible terms. Nevertheless, the viewpoint being argued seems plausible enough as an honest statement of opinion by a real Muslim.]

From a Christian perspective, the basic mistake here is thinking of the law of Christ as if its main purpose was to be a terrestrial law code. From this perspective, a law could deviate from perfection either by being "too strict" or by being "too lax", given the realities of human nature. Yet Christianity is not primarily meant to be a new code of laws, but rather it is a means of experiencing supernatural grace. From that perspective it is an attraction, that the law of Christ cuts deeper than anything we could obey by our own efforts. Suppose that our "terrestrial nature" is indeed destined "to mount up to Heaven"; not indeed by our own efforts, but rather by the grace of God redeeming sinful people, and conforming us to the supernatural standard of goodness set by Jesus? Then we need to know what truly heavenly people would look like, and Jesus provides that picture.

Muslims admire Islam for the reasonableness of its requirements. For example, if you are physically unable to prostrate or to go on pilgrimage, then God understands that, and you can just do whatever you can do. On the other hand, while Christians certainly believe God makes allowances for our weakness, we admire the Gospel message more for its unreasonableness by human standards. God demands that which exceeds our abilities; but then gives us the grace to fulfil his commands.

Islam and Prophets

This issue is closely connected to the Islamic theology concerning prophets. Most Muslims believe that all prophets are sinless, which would blatantly contradict the Bible in numerous places. However, I have come to conclude that this doctrine was never taught by Mohammad; in particular it seems to explicitly contradict the Quran, which contains multiple examples of prophets sinning (e.g. there is a story of Jonah similar to the Bible, Mohammad is rebuked by God for doing certain things, etc).

Nevertheless, there is still a significant difference when it comes to the overall tone of respect which the Quran has for prophets, as compared to the Bible which consistently emphasizes the flaws and sins of nearly all of its major protagonists, except for Jesus. Leave aside the villains; let's look at the saints: Noah gets drunk; Abraham lies about his wife; Isaac plays favorites; Jacob tries to trick everyone; Joseph's brothers sell him into slavery; Judah visits a prostitute; Aaron makes a golden calf; Moses loses his temper; Jephthah swears a rash vow; Samson is a violent hothead; David commits adultery with Bathsheba; Solomon is led astray to idolatry; Hezekiah boasts to the Babylonian envoys; Zechariah doubts the angel; Peter repeatedly wavers in his faith; Paul is quarrelsome. Even Mary, the Blessed Mother of the Lord, comes to try to take Jesus home to cool off, after the rest of his family decides he's gone nuts! This is all rather astonishing, especially given the tendency of other religious literature (including later Christian chronicles and legends) to succumb to pious hagiography. To my mind this moral realism is one of the most striking effects of divine inspiration, in the narrative parts of the Bible.

(Conversely, one of the most striking aspects of those parts of the Bible in which humans talk to God—like the Psalms and Job—is the brutal honesty with which the saints are allowed to express their feelings to their Lord. Here too, I know of no real parallel outside the Judaeo-Christian tradition. It is certainly not a common practice in Islam.)

The Muslim attitude is, how can you trust a prophet if he's a sinner? Which makes perfect sense if you think that sin is just a matter of disobeying some reasonable code of conduct which any decent person is capable of following. But the Bible provides the more bracing truth that everyone is a sinner who needs salvation (Christ alone excepted). Even heroes of nonviolence, like Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., can commit quite serious sins (as a close look at their biographies will reveal).

The Gospel passes judgement even on its own messengers, "so that every mouth may be silenced and the whole world held accountable to God" (Romans 3:20). The Christian doctrine of original sin is much maligned, but as St. Chesterton pointed out, its actual effects are to promote sympathy and solidarity between human beings. We are all in the same leaky boat, and we all need rescuing! Righteousness is something which we cannot achieve by merely human efforts, even if those efforts take the form of religious rituals (praying X times a day, going on pilgrimage, donating to charity etc.)

What is Grace?

Another way of putting this: Islam is inherently Pelagian in its theology of human nature. (St?) Pelagius—despite the fact that he was himself a very devout and pious man—was condemned for his heretical and destructive teachings by the Catholic Church. The problem was that he taught that human beings are morally capable of obeying the law without needing to undergo a radical spiritual transformation. On a Pelagian (or Islamic) view of salvation, the main spiritual need of humanity is to be educated and informed about what it is that God commands. Having learned the correct way to live, our task is choosing to submit to God's commands and obey them, which we have the power to do. But orthodox Christianity teaches, that what humans need is not primarily instruction, but rather an infusion of new life which comes from on high.

What kind of grace do we need? The Quran portrays God as merciful to believers, but he does not show extravagant love to sinners as he does in the Bible. Indeed the Quran seems more frequently to relish in the damnation of evildoers, rather than mourning them. Compare this to the biblical tradition: "As surely as I live, declares the Lord God, I take no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but rather that they turn from their ways and live!" (Ezekiel 33:11).

In my experience, it can be a bit difficult for Christians to communicate our theology of grace to Muslims, since it is easy to overstate the difference between the two religions, when in fact there is a lot of common ground.

If you try to tell your Muslim friend that it is impossible to be good without divine help, they will almost certainly agree with you! This is just common sense, in any tradition of ethical monotheism. Pelagius himself would never have said that God doesn't help us to do good works, or that it is wrong to pray for his assistance in being good. After all, God created us, and nothing in the world can even continue to exist without his active sustenance. (Even the most hard-core Calvinist ideas about divine predestination have parallels in Islamic theology.)

If you try to talk about God's mercy—well it is also very important to Muslims that God is merciful. In all five of their prescribed daily prayers, they invoke "the Name of Allah—the Most Compassionate, Most Merciful" (Sura 1:1). If you ask them whether it is always possible for even the most sinful person to repent and be forgiven by God, again your Muslim friend will probably agree. Assuming the sinner is sincere in their repentance, and they earnestly desire to live a righteous life going forwards, why wouldn't God accept them?

But as we have seen, what the Bible means by grace goes deeper than this. In the New Testament, God pours out his love and grace even to those who are currently his enemies. There is no analogue in the Quran to divine "love" in the sense of: "For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son" (John 3:16), nor to "sacrifice" in the sense of: "While we were still sinners, Christ died for us" (Rom 5:8). In fact, there can't be any parallel, because it would be considered blasphemous to say that God has a Son, or that anything which God does, can be compared to being a crucifixion victim. (As discussed previously, Islam does not even seem comfortable with the idea of purely human prophet experiencing such a fate.)

And as for the human response to God's grace... suppose we consider the most law-oriented book of the New Testament: the epistle by Jesus' brother James. This letter considers its most essential task, to be convincing Christians to obey Christ's "perfect law of freedom" (1:25), and it says that "faith without works is dead" (2:26). If a Muslim scholar wanted to identify the stratum of early Christian teaching which is most compatible with Islam, they would probably pick this letter. And yet, even in this book, St. James strikes a note totally incompatible with Islamic (or Pelagian) theology:

Every good and perfect gift is from above, coming down from the Father of the lights, with whom there is no variation or shadow of change. By his own choice, he gave us birth by the word of truth" (1:17-18).

Or as Jesus said to a Jewish religious leader, "You must be born again" (John 3:7). This refers not to our natural birth, but to a spiritual birth into a new life which comes from God! Receiving this new life from God, makes us truly children of God.

While obviously this does not refer to literal procreation in an earthly sense, Jesus' use of a biological metaphor here still communicates something deeply important. When Christians call God "Father", we do so not as a mere title of respect (though he is worthy of all respect, nor do we call him "Father" simply because he looks after our needs as a parent does (though he certainly does that as well). Neither of these would require any notion of "new birth". Rather, we call God Father because he has enabled us to participate in his own spiritual life, which we receive from Christ. This divine life cannot be replicated simply by human effort. (This would be just as impossible, as for a woman to get pregnant by looking at pictures of babies.) This is why, throughout the Gospels, Jesus continually talks about receiving the word of God using agricultural metaphors: seeds growing into plants, vines nourishing branches, etc.

We come to Christ because we have had the experience of being unable to live up to even our own moral standards; and we find forgiveness and hope there, and a grace that seems to touch our point of need. To say: "the problem is you were trying to follow moral rules that were too hard, just do these other rituals instead, and remember that God is merciful" seems like it is missing the point. My own spiritual needs cry out for something deeper than that.

And then Christianity offers something far greater than we had any right to expect. We believe that those who are in Christ, become spiritual sons and daughters of God, living by the power of God's own life. Even though we are human and not divine—and however inadequate our current strivings may be—the purpose and goal of our sainthood is nevertheless to become, in some inconceivable manner, spiritually united to divinity. As closely as a husband is united to a wife, or as a mother to her unborn child, or the soul to the body. This is a relation to God that Islam does not offer, and cannot offer, given its other theological commitments.

Hence, from the perspective of someone who believes this central Christian gospel (the good news about Jesus), the Islamic religion simply doesn't come across as a mere extension or addition of new material. Rather, it is a denial of what Christians consider to be the good news: that God did for us, and will do in us, a work of righteousness which goes beyond human capabilities. In the moral realm, we need somebody who can say to us, what Jesus said to the crippled man: "Pick up your mat and walk!" (John 5:8).

VI. Hinduism

To find a religion which competes with Christianity in its desire for mystical union with the divine, we now turn to the East, to the religions of India. In this section we will look "Hinduism", although in fact this is a pretty broad target, containing a very eclectic group of different philosophical traditions, which are really only regarded as "one thing" as a result of being grouped together by British Imperialists. As these traditions are practiced by different groups of people, there is no obligation for these ideas to all be compatible with each other, so it is very difficult to discuss Hinduism in any sort of unified way. There is a lot going on here. Some of it good, and some of it bad.

Traditional Hinduism is fairly closely bound up with a system of racial subordination, which it grew up around. It's hard for me to get too worked up about this at the personal level, not being Indian, and I don't want to overstep when judging a culture different from my own. But if there were a hypothetical American religion which taught that black people shouldn't necessary aspire to the same religious goals as white people, but should follow the duties of their own traditional station in life, in hopes of being reincarnated as a white person... then I think that religion would strike me as being pretty evil!

By contrast, the popular Bhakti (devotion) movement in Hinduism teaches that one can gain salvation through devotion to a particular deity (or set of deities), and that this devotion transcends caste divisions. These reform movements became very popular in India, starting in the 15th century. Perhaps this was in part due to influence from Western religious concepts. Different religions do not actually exist in watertight compartments; they influence each other in various ways.

The mythology associated with Hinduism, like other pagan mythologies, often does not portray its deities as holy and righteous, but rather as petty, selfish and sensual. This shows that these gods are only idols, made in the image of our own flaws in order to tell a good story. Even if they were real, they would have no moral authority, because they behave no better than the powerful and rich rulers of our own species.